25 Jan Blinded By The Might

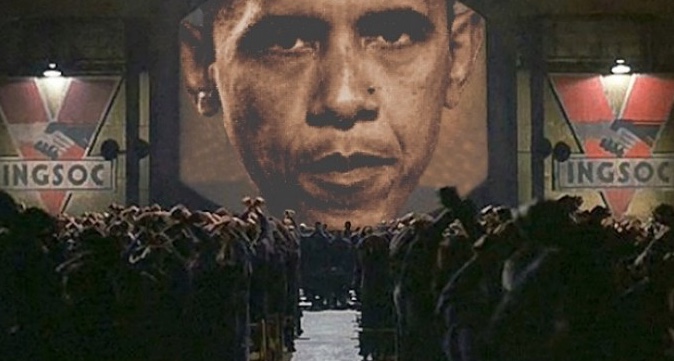

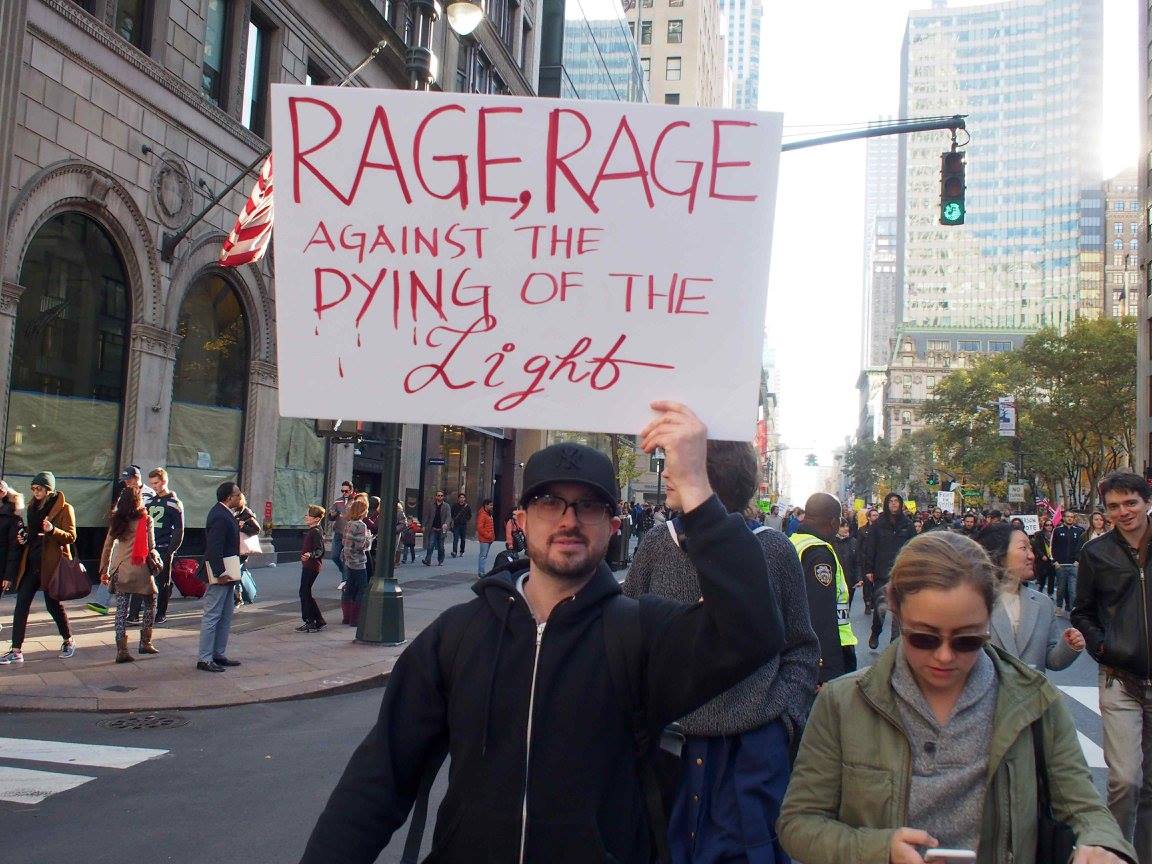

George Orwell was working with profound insight when he envisioned the “two minute hate” in his novel “1984”. When we are enraged, our ability to reason goes out the window; rage leads to blindness. It is hypnotizing and intoxicating; enraged people are much more susceptible to the power of suggestion, and more easily controlled. The more that Donald Trump and his allies whip up the rage quotient, the more power they amass. However, the Republicans are not the only ones who try to use rage to muster support – they are just much more direct about it than their Democratic colleagues, and therefore more successful. In the end, though, if most of the population is enraged, there is very little room for rational discussion or thought. Donald Trump knows this better than anyone else – ever – and uses this knowledge with uncanny accuracy.

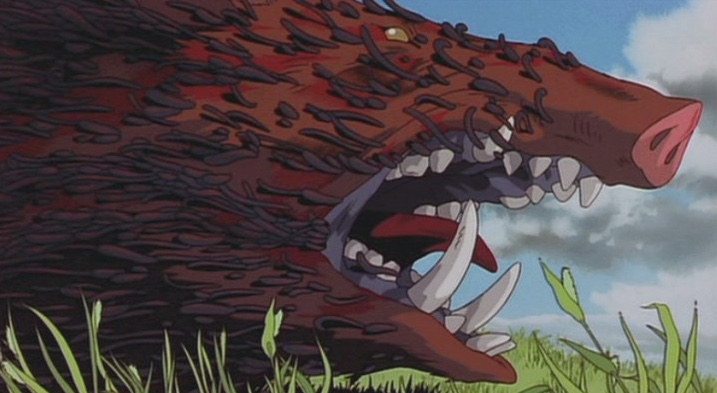

The master storyteller, Hayao Miyazaki, also recognizes the profound power of rage. In his film Princess Mononoke, several of the main characters become so blinded by rage that they lose all sense of balance and are turned into demons, from the inside out. The boar in the above image, the leader of his clan, becomes so enraged after being shot that he blasts ceaselessly through the countryside until he is finally killed by a young warrior. However, the boar’s rage is so profound that it leaps off of his lifeless body and infects the young man who slayed him, Ashitaka. As the wound begins to spread, threatening to overtake him, he goes on a “hero’s journey” to find peace and relief. The religious scholar Joseph Campbell coined this term, hero’s journey, after recognizing that it is central to almost all culture’s myths. The hero goes on a quest to restore balance to a world in the throes of conflict between good and evil. In most myths, the hero does not and needs not vanquish the darkness completely, but instead brings them back into balance. There can be no good without evil. They are countervailing forces that require each other to exist; Yin and yang.

In Princess Mononoke, the genesis of the rageful boar is a bullet from the gun of a character who is not purely evil. Instead, Lady Eboshi is a firm leader who is good to her people. However, her desire for dominion over the natural world has put the balance between humans and nature out of whack. This desire for power has clouded her ability to see the damage that she is inflicting on the world around her. Thankfully, Ashitaka has such immense inner strength that he is able to resist the rage that fights to overtake him. His clarity of vision allows him to address each of his conflicts with an open heart and a desire for peace. Rather than see Lady Eboshi as a foe to defeat, he challenges her with respect and empathy. Eventually, at the moment of calamity, he helps to restore her vision and together they take steps to shift the world back into balance.

The classic hero’s journey in the West is not usually this complex or nuanced. In Star Wars, or World War II movies, the stories we tell tend to paint the villain as power-mad; purely evil. In these scenarios, the only way to restore balance is to vanquish the villain completely. However, true balance is not restored by annihilating an opposing force. The word balance has many different connotations, and while it can describe the state of being in harmony, some of the definitions point to the ACTIVE nature of the verb. These definitions clarify the idea that maintaining balance requires direct action.

“equipoise between contrasting, opposing, or interacting elements < … the balance we strike between security and freedom. — Earl Warren>

In this understanding, being in balance is far from restful or static, but instead requires constant attention and action, involving a push and pull between opposing forces. Again, that idea of yin and yang. Due to the power of gravitational pull, water constantly seeks a low point. Yet it’s own internal gravitational pull causes it to form into droplets. The conflict between moving towards beading up into droplets, and the pull of the external force of gravity, is far from static. The drop hanging off the grass in the above image is not long for the world. In this case, this conflict between balance and imbalance creates a point of interest.

As the quote from Earl Warren makes clear, balance is not only relevant in regards to physical forces, but to emotional ones as well. Throughout the course of known history the conflict between differing philosophies has resulted in a pattern of change whereby one idea overcomes another opposite idea. It is not simply a case of good battling evil. We can also see the will for power versus the will towards god, or the will of the people versus the will of the individual who wants power. Sometimes these changes are seen in the form of a “revolution”. At other times the change happens in such small increments that we only notice that they have occurred in retrospect.

In our film All The Rage, we address the issue with an animation that has the following as a voice over. “Human knowledge is constantly evolving and in medicine there’s always been a tension between the weight given to the mind and to the body. The 17th century philosopher Rene Descartes got into a conflict with the church about this issue. In order to save his own head, he agreed to leave the mind to the Church and focused his attention on the body. It took a couple of centuries before Freud and his colleagues brought the mind back into the realm of science. And the mind-body connection became the focus of a great deal of medicine, not just psychiatry. Then, somewhere in the middle of the 20th century, the tools of science became increasingly technical and mechanical. Scientists made incredible discoveries like antibiotics and vaccines. And the role of the mind, which was much harder and messier to study using the scientific method became increasingly ignored.”

When technology came into play and people could peer into bodies with more insight, this process accelerated so much that by the end of the century almost no one within the medical establishment considered emotions to be a causative factor in pain syndromes. As they worked to deal with an increasingly powerful epidemic of pain, they continued to treat the problem with drugs, surgery, physical therapy, and devices. When doctors don’t consider the emotions to be relevant to their health issues, patients follow their lead. However, at the beginning of the 21st century, a wave of research began to slowly crest. That work is now beginning to appear in journals and the tide is turning. While our culture is still resistant to considering emotions in regards to health, the balance is shifting back towards a consideration of both physical and emotional aspects of illness.

As we have worked on All The Rage, we have struggled against quite powerful resistance to the idea that pain often has an emotional basis. There is currently such a strong cultural bias towards physical reasons for our pain, that many people simply can’t believe that emotions are at play in the problem, even if they are presented with powerful evidence. People who have back pain and have had an MRI feel especially wedded to the physical diagnosis they have received, because they can see the tissue on the film they were handed by the doctor. Dr John Sarno, the main character of the film, began by practicing based on the physical diagnosis that he was taught. However, he had very little success in relieving his patients of their symptoms. He also found that the physical diagnosis that people were given often didn’t match up with WHERE they felt pain. For example they might be told they have a herniated disc pressing on a nerve, but the pain rarely corresponded directly with the supposedly affected nerve. After finding that many of his patients also suffered from a host of psychosomatic issues such as migraines, colitis, excema, and ulcers, he began to talk with his patients. Dr. Sarno came to see that many of them were perfectionists, constantly putting themselves under great pressure to be good. When he guided them to make the connection between their pain and the repression of their emotions, they got better. The pain was relieved. A cure was born.

We’ve been working on our film for a dozen years, and recently completed it. As discussed above, we understand the way in which conflict is a driver of the stories that we tell. Humans are drawn towards telling stories in which the forces of good bring balance back into the world by battling the forces of evil. These kind of stories help us to define ourselves in relation to our culture. Earlier in this piece, I pointed out that in the US, the Republican approach to inciting rage in their followers is less nuanced and more direct than that of their Democratic rivals; and therefore more effective at inspiring rage. Rage tends to both blind people and unify them at the same time. People who rage together form mobs. If one has a will towards power, mobs are useful. However, if one has a will towards balance, mobs are a problem. Potentially fatal.

All The Rage is aimed at helping to restore balance. We had to be very mindful about not inspiring rage. The film focuses on Dr. Sarno, who is somewhat conflict-averse. While his theories are at odds with the medical community, he did not take on that community as an adversary in public. Instead, he continued to refine his treatment methods through careful and deliberate interaction with his patients. As a practitioner, he did not engage in a robust research practice. Instead, he wrote about his observations in a series of books. At first, he attempted to engage with his colleagues, but the medical community simply ignored him. So, he used his books to communicate directly with people, and over the past 30 years, millions of people in great pain have read his books, and many of them have had what could be said to be somewhat, or flat out, miraculous recoveries.

As we worked on the film, many people pushed us to take on the medical industry in a very direct way. People who understand or who have been saved by Dr. Sarno’s ideas often have a desire to convince others that he is right. However, when we looked at this in a more global sense, we understood that while a dogmatic, directive approach would enable us to rally his followers, it had the potential to alienate all of the people who don’t already agree with Dr. Sarno, or even know of his work. When people who are resistant to an idea are challenged directly, they can become enraged, and may cease to listen. So, rather than seeing the medical industry as the enemy, we understood we had to move forward in a careful, deliberate, and empathetic manner. While amping up the conflict level between Dr. Sarno and the medical industry might have made a more conventionally compelling film, it could also make it harder for those haven’t already come to understand the power of the mind body connection to embrace the ideas. In the end, this will make the film a more effective tool for bringing equipoise back into balance, but it creates obstacles for getting it seen. Sandpaper is not the same tool as a saw, but they can both be used to help level a table. The sandpaper takes a lot longer, but there’s less risk of going to far.

Recently we sent All The Rage to an important film programmer who declined to show it. He offered to share his reasons for passing. Part of his note reads, “For the most part, we were left with the impression that this is a near-miracle cure, so to speak, given the preponderance of positive testimonials and lack of significant skeptics. Is this really the case – are his recommendations so on-point and the results of his advice so overwhelmingly positive that there’s little controversy here? How does the leadership at NYU feel about his work?”

The film actually takes great pains to point out that Dr. Sarno is a controversial figure. However, he’s also fairly private and he didn’t want to go into how he was treated by the institution he worked at for over 50 years. Since the whole medical community was skeptical of him, it didn’t seem necessary to trot out talking head experts to tear him down. I also pointed out to him that while reviews on Amazon are not scientific- it is interesting to study the reviews of Dr. Sarno’s book on Amazon- 74% are 5 star reviews. 10-4 star. 7 percent are 1 star. As Dr Sarno points out, if people buy into his idea, they get better. If they resist it, it doesn’t work. This theory seems to be borne out, by not only these numbers, but also by what people write about their experience in very personal testimonials. While some one star reviews articulate that the person bought the concept but did not get better, most of them indicate that they were very skeptical to begin with. One thing that we did not get into in the film is the idea of the placebo effect- which is often considered a fake, or magical result. Instead, we can look at this effect as being connected to the activation of belief. Perhaps it is true that if we believe we will get better, our bodies respond positively.

Sometimes it is almost impossible to see past the cultural narratives that shape our lives. As Dr. Sarno’s concepts lie in stark contrast to what the rest of the medical community is prescribing to patients, it is hard for people to believe them. In fact, very few people are able accept the science that points to the truth of what he’s saying, so they simply ignore it. All of the studies that have been done on the relationship between herniated discs and pain find that there is no causative correlation. This is to say, just as many people have herniated discs and no pain, as those who have pain. As well, when a doctor is asked to predict who has pain and who doesn’t when looking at MRIs alone, they cannot do so with any real accuracy. These studies have been coming out repeatedly for more than a decade, yet practice and treatment has essentially not changed. When we started the film in 2004, I saw an article about this issue in the NY Times by Gina Kolata. I asked her to talk to us for the film but she refused. Since then, she has published 3 other articles. In the most recent one from 2016, she looks back with wonder and asks how this mountain of scientific evidence has done almost nothing to change either the way doctors and patients approach the problem.

With Costs Rising Treating Back Pain Often Seems Futile. – 2004

Study Questions Need to Operate on Disc Injuries – 2006. (disc herniation doesn’t correlate with pain- and no evidence is an “injury”))

The Pain May Be Real But The Scan is Deceiving – 2008

Why “Useless” Surgery is Still Popular – 2016

I imagine that after reading my email this programmer is wondering why we didn’t simply put this information in the film. The truth is, this information is enraging to read. While rage gets people riled up, it rarely turns skeptics into believers. Instead, when we bait people with information that is contrary to their belief system, their rage often causes them to reject the ideas, in spite of the overwhelming evidence and proof. Those who already believe it is true get enraged, too, but that rage only creates more division. We made a conscious decision to do what we could to engage people on a personal and emotional level through our characters, rather than through talking head experts, or facts. As a character in the film, Dr. Sarno is on a gentle mission to get his message out, and I am trying to help him with his mission, and also struggling to heal at the same time. While the film isn’t driven by the kind of conflict that gets our hearts pumping and filled with adrenalin (a potentially toxic effect, by the way), our hope is that it is the kind of film that can lead people to have a change of heart. And to healing.

No Comments