20 May The Lehrer Conundrum

We are at the point in editing “All The Rage” where we had hoped to include both the ideas and words of Jonah Lehrer. As I detailed in this piece a couple of years ago, while doing research for the film I came across an article that he wrote for Wired called, “Trials and Errors: Why Science is Failing Us“. In the article he articulates a number of ideas related to our project that I had struggled to put into words. His article also pointed to the data on MRI’s, disc herniation, and pain that called into question the idea that herniated discs were responsible for pain, so there was a direct connection to our film about Dr. Sarno and back pain. I immediately looked him up on Facebook and it turned out that my brother, who is a social psychologist, was a mutual friend. I reached out to Lehrer to see if he would be willing to do an interview and he readily agreed.

I then read his first book, “Proust Was a Neuroscientist”, which detailed the ways in which a range of artists had dicussed how the brain worked at the turn of the century. In general, their work conceived of processes that were at odds with the prevailing brain science of the time. As he shows, in large part, modern science has proven the artists’ intuition to be much more in line with the modern conception of the way the brain works than the scientists of their day. The book seems to argue that it often takes an artist’s mentality to see around the frames that so frequently blind us to ideas that challenge the foundation of our thinking. Like the artists that he wrote about in that book, Lehrer takes an artistic, challenging and creative viewpoint when it comes to scientific studies. While some scientists, like my brother, appreciate the stories that he spins from their research, others are less enthused.

Not only did I feel a kinship with his work in terms of the ideas, but also in the way they poke and prod at dominant ways of thinking. There are some journalists and scientists who take a much dimmer view of his work than I, but his writing has been very popular. In a very short period of time, Lehrer wrote several best sellers, and hundreds of blog posts. He was so prolific, and his posts were so widely shared, that the New Yorker hired him as a staff writer. He was the youngest person they had ever hired. His rise was fast, but his fall was explosive.

When both journalistic and scientific problems began to be pointed out with his work, the journalists and some scientists were quick to pile on. First, there were revelations that he had plagiarized from his own work; taking bits that he had written for one blog post and re-using them in another (often for a different outlet). If you have ever read what I write, I tend to recycle ideas on this blog like beer bottles. As I try to drill down deeper into an idea, I often re-write myself. For me, this is a space to work out ideas, get feedback, and move forward. This article is a case in point. I have really struggled with the issue of how to use Jonah in the film, so much of what I am writing here I have already written about numerous times.

Then, it came out that he had cobbled together 5 Bob Dylan quotes for his book “Imagine”. It got more problematic when he lied about it to cover his tracks. That was a very big mistake and was impossible to overcome. Trust is essential in all relationships, be it romantic or one between a writer and their readers. If we don’t trust the person with whom we are communicating, we lose all sense of balance.

Up until this point, I didn’t share the indignation that had been lobbed Lehrer’s way. Cobbling together of quotes, while problematic from a “journalistic” perspective, is pretty much what documentary filmmakers do all day long. A cutaway to a clock, or a punch in to a tighter shot is a kind of defacto ellipsis, which most viewers unconsciously understand means that some editing is being done to what’s said. Film editors constantly trim away fat to get to a quote that makes sense, or make the point more clearly. While I understand that the rules of journalism are important, I also tend to appreciate artists who push at rules in ways that reveal the problems that the rules create. Rules are important to establish order, but there can be so much order that they limit the ability to see around them. When I read about how Lehrer had at first lied to the writer who questioned him about the Dylan quotes, and then, upon realizing how bad it was, had called him 24 times in one night, I felt more empathy than anger. This is probably because I wanted him to be ok because I had gotten a lot from his work and had felt grateful for his generosity.

Lehrer was swiftly and brutally punished for his transgressions on blogs and the twitter universe. Part of the anger undoubtedly stemmed from how far and how fast he had risen in his field. Further, not only did he publish at a furious pace, but his work also closely resembled that of a more successful counterpart, Malcolm Gladwell, and Lehrer was accused of cribbing liberally from Gladwell’s work. His fall from grace was so profound that it takes up two chapters in Jon Ronson’s recent book, “So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed“. Slate’s Daniel Engber was one of the most pronounced shamers, and his reaction to the book was not as positive as most other reviewers (which generally got raves from place like NPR to Jon Stewart). In fact, Engber doesn’t think he has been shamed nearly enough.

Am I monstrous for saying so? Perhaps some readers will agree with Ronson that Lehrer has had enough excoriation. But I don’t think it’s cruel to worry over facts, and the narrative that Lehrer has begun to spin — with assistance from the Ronson book — skirts the depths of his misdeeds. Lehrer has a book out in September (co-written with behavioral economist Shlomo Benartzi) about online thinking and behavior, and then another of his own in 2016, about the power and meaning of love. Before we read these chapters of his comeback, let’s remember what he did.

Engber has valid points that there were problems with Lehrer’s work. His biggest beef is that he doesn’t play by the rules. His final paragraph, following a discussion of Lehrer’s recent essay on redemption reads, “I hope that Lehrer finds a way to fix his life, and that it makes him generous and happy. I hope he makes a living, writing books or otherwise. But there are rules to telling stories, even stories of redemption. You can’t fabricate forgiveness.”

As you can see from my earlier post, I found the attacks on Lehrer frustrating because I had found a great deal of value in his work. As someone who has had a hard time with rules myself, I also understood that he was perhaps playing a different game than writers like Engber expected him to be playing. As filmmakers, my partners and I exist in a grey area between journalism and art. While we often focus on documenting stories that are taking place in a larger media universe, much of our process is focused on illuminating the disconnect between what “the media” is presenting and what is going on for the people personally. At the time I was reading a lot of Lehrer’s work, I was also busy dealing with the distribution (or lack thereof) of our film “Battle for Brooklyn”. Reviewers tended to dismiss the underlying ideas of the film – that the media had done a terrible job, that the politicians were corrupted, and that the developer at the heart of the story was controlling the narrative through their powerful PR campaign. I’ll post the entire The NY Times review by Neil Genzlinger here because it is short, and illuminates a great deal about the universe that the film lived within.

“Battle for Brooklyn,” a documentary about the unending mess that is the Atlantic Yards project, is unabashedly slanted and as a result will probably be dismissed by those it portrays unflatteringly. That’s unfortunate, because this film should be discouraging and dismaying for people on all sides of the project, for what it says about oversize expectations and missed opportunities.

Michael Galinsky and Suki Hawley certainly know how to edit film to make public officials sound like manipulative weasels or clueless buffoons, and that’s what they do here as they tell the story of Bruce Ratner’s billion-dollar plans for a huge Brooklyn development centered on a basketball arena, and the residents and businesses displaced by it. One particular apartment owner who held out to the last, Daniel Goldstein, is the focus of the film, which was shot over eight years. In the course of it, he goes from reluctant victim of a developer’s unstoppable plan to ardent activist, affecting his personal life in dramatic ways.

The film is full of bombastic promises about jobs and other benefits from Mr. Ratner and the politicians who support him. With the project now a shell of its former self, they seem particularly outrageous. But it will be years yet before the definitive story of this exercise in urban reinvention can be told.

While the review seems fairly positive (it was a Critic’s Pick, for example), it explains to the reader that we are not to be fully trusted. I would argue that it is the Times that might have a trust problem in regards to this project. I found out about the project after the New York Times covered a press conference. One of their first articles was titled “Curbside seats at an Urban Garden”, and its first line read, “A Garden of Eden grows in Brooklyn.”. What the article fails to mention is that at the same time this came out, The New York Times was hard at work building a new skyscraper in Times Square in financial partnership with the developer of this “Garden of Eden”. The NY Times building was being constructed on a site that had been seized via eminent domain from another developer who had plans for it. The Times’ continued coverage of the project was slightly more exacting than this, but not much.

It’s no wonder then that even their film writer found it hard to believe that the developer’s bombastic promises were completely empty, or that politicians had very little grasp of what was going on, or that the developer had so much power in controlling the narrative. By the time the movie was released, shortly before the arena which is the centerpiece of the development was completed, it should have been clear that the promises of affordable housing and local jobs were empty because so many of them had already been broken. Four years later, it is devastatingly clear. The project was sold on the idea that it would provide jobs and housing. It did neither, and had done neither by the time this review ran. On the eve of the arena’s opening, The Times ran a beautiful ode to Brooklyn and basketball written as an op-ed by the filmmaker Dan Klores. Surprisingly, the editors at The NY Times failed to determine that the fact that Klores Communications ran PR for the project and took in millions of dollars for this work might be a conflict of interest. When they were alerted to this fact, they refused to add a note or correction to the article. The narrative that Klores’ company had so carefully crafted – that the opponents of the project were selfish malcontents and that the developer and the government thought only of the greater good – was so powerful that Genzlinger, and almost everyone else, had a hard time getting past it. The developer’s PR machine accomplished this feat by driving the news stories through carefully curated press conferences. At one such event I was shooting outside when a young PR staffer pointed me towards the conference. I went in, but was quickly turned away because I wasn’t “credentialed”, and they didn’t know what I would do with the material. This press conference was taking place in side a State court building that was built and owned by Ratner. It was taking place across the street from a hearing about the environmental impact of the project. The conference featured pro basketball players talking about how great the project was.

press conference? from rumur on Vimeo.

In the end, we weren’t directly attacked by the media for our work, but instead treated somewhat patronizingly, and largely dismissed. The story we were telling ran so counter to the overwhelming narrative created by the developer, that even those people, perhaps especially, who worked in the media, had a hard time accepting that perhaps our film wasn’t edited to make the politicians look like buffoons, but instead that they had acted like them.

It was only after the Occupy Movement happened that people had a framework within which to understand our film. This kind of framework is so important, and Lehrer’s work played a similar role in helping me gain a better understanding of the ideas I was struggling with. Since so much of our work takes a hard look at how stories play out in the real world through media, I have a much dimmer view of journalism than most journalists do. On the flip side, since as filmmakers we don’t try to fit within the structures and rules of journalism, journalists perhaps have a dimmer view of what we do.

When we are a part of a system, it is often incredibly difficult for us to see its structural faults. This is largely what Lehrer’s work is about. Margaret Heffernan writes a lot about this idea in her book “Willful Blindness”. This idea is central to our new film, “All The Rage”.

While Leher’s essays looked like journalism, and dealt with science, they weren’t scientific papers and they were more focused on good storytelling than on the “who, what, why, when, or where”. Like Mike Daisy (also profiled in Ronson’s book) or Werner Herzog, Lehrer perhaps focused more on the “emotional truth” of his stories than the truth with a capital T. Again, this is not to say that the issues brought up in regards to Lehrer’s transgressions aren’t worthy of discussion and correction. However, it’s sometimes hard for me to see eye to eye with Engber’s righteous anger. For example, he spends a good bit of his time ripping into Lehrer for borrowing liberally from a book about Tom Brady for a chapter in his book.

Those “mistakes” are already on the public record. It’s all too easy to unearth more. A few days ago I looked at the first chapter of How We Decide, which describes quarterback Tom Brady’s Super Bowl–winning drive against the St. Louis Rams in 2002. Lehrer’s account of those 81 seconds closely follows one from Moving the Chains: Tom Brady and the Pursuit of Everything, by Charles P. Pierce, which also tells that story in its first chapter. Lehrer cites the Pierce book for two specific quotes, but his game analysis and structure are more or less the same. Some sentences are copied word-for-word, like this one: “The coaches were confident that the young quarterback wouldn’t make a mistake.”

What Engber fails to see is that Jonah Lehrer is not really focused on the Tom Brady story as a way of talking about Tom Brady, but instead using the details of this story to set up a much broader discussion. I don’t get the sense that Lehrer is insinuating that he did a great deal of original reporting on Brady. He perhaps could have done a better job of citing his sources. However, the fact that he didn’t cite the source well doesn’t have much to do with the larger point about decision-making that he is making.

Again, the discussion is important, and the corrections should be made. There is no doubt whatsoever that Lehrer made a lot of mistakes. However, his work resonated with me in a myriad of ways, and I forgive him his sins, partly because I fail in many of the same ways myself. I rush to post things before they are finished, and I don’t pay a lot of attention to the rules of journalism. For the most part, I’m trying to work out ideas, which means a lot of them aren’t fully formed. However, I’m not under any scrutiny, no one’s paying me to write, and not many people are paying attention anyway.

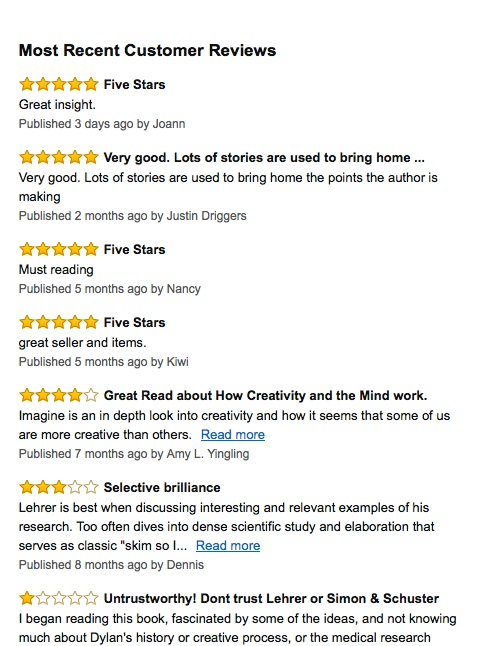

It’s been nearly two years now since the scandal, and even though “Imagine” was pulled from the shelves, Engber will be very frustrated to find that according to the most recent Amazon reviews people continue to find a lot of value in it. The same is true for “How We Decide” and “Proust Was a Neuroscientist”.

As filmmakers we face a real dilemma. Lehrer’s work was incredibly important to our process, and he graciously agreed to several interviews. In those interviews, he gave us fantastic material to work with, that cleanly and clearly makes the points that we want to have in the film. However, because of his vast public shaming, many people – including Jonah himself – have told us it is unwise to put him in the film. While it is true that we could shoot an interview with someone else who could make the same, or similar, points, I am very resistant to ignoring the role he played. We are working to figure out how to weave what happened to him into the story. I hope that we can, because it is relevant to the complex tale that we are telling. While “All The Rage” is about Dr. Sarno and mindbody medicine, it is also very much about how ideas move through the world, and the complex and often unconscious frames that shape our thinking. It may be too much of a diversion from the story, but I will continue to struggle with it.

No Comments