The Klan in Color

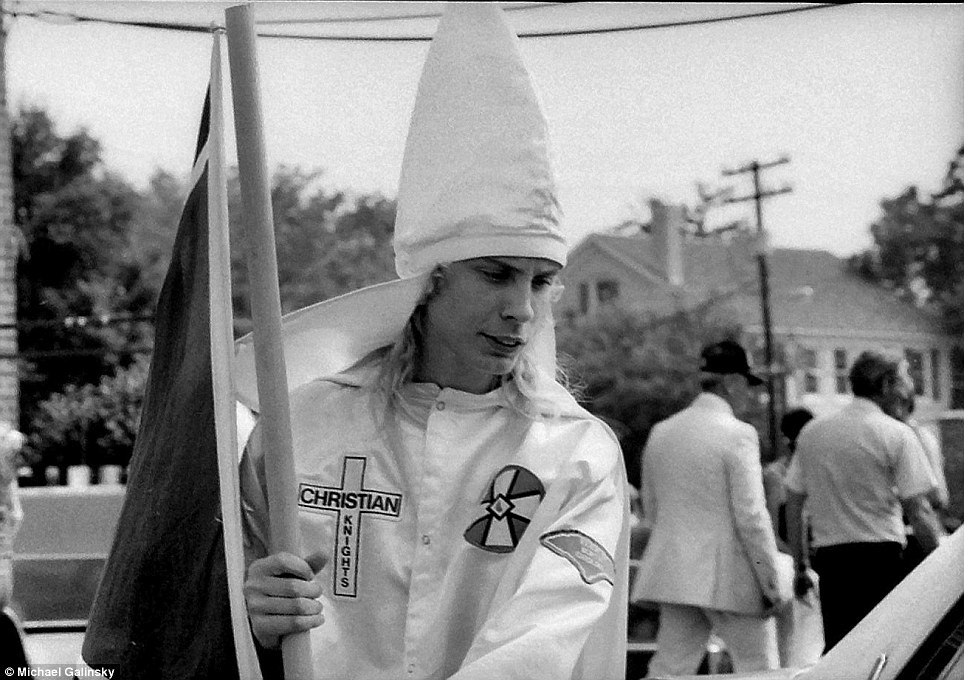

A couple of weeks ago, I was scanning some color slides when I found a box with about a dozen color images that I shot at a Klan rally in my hometown the day after I graduated from high school in 1987. There weren’t a lot of Klan supporters where I lived, so their rally was a provocation more than anything else. Honestly, it felt like the last gasp of a dying group. A few years ago I found the black and white images I shot that day. Those images feel wildly different from the color shots because the black and white makes them feel like vestiges of the past; their look gives them a sense of distance from where we are. However, given the current state of our culture, the color images feel eerily present and familiar – especially because the situation has repeated itself now 30 years later.

I grew up in Chapel Hill, NC, a small college town that has prided itself on its liberal bona fides for decades. In fact, in the ’80’s people bragged about the fact that U.S. Senator Jesse Helms flatly stated that they should put a fence around the town and call it the North Carolina Zoo. During my childhood, UNC’s basketball coach Dean Smith was the moral pillar of the community. He had a very different view of the world than Senator Helms, and was a strong supporter of work that was being done to dismantle the de facto segregation that still existed here in the late ’60s when he arrived from Kansas (where his father, a basketball coach wrote an amicus brief in support of Brown in Brown vs Board of Ed). Not only did he recruit Charlie Scott, the first Black collegiate basketball player in the ACC, he also worked closely with religious leaders and civil rights activists, using his standing to help quietly desegregate restaurants and other institutions.

While I’m “from” North Carolina, both of my parents were Jews from the Northeast who moved South to teach at UNC. As a child, I didn’t have a way to articulate an understanding of the delicate balance that exists between the influence of community and family. Both our genes and the behaviors/culture of our parents have a profound impact on who we become, as do a myriad of cultural influences from outside the home. The dissonance between those influences push and pull at us in ways that we don’t fully understand and many of us spend much of our adult lives trying to unpack those influences and impacts. After three months of living in New York for college, my dual identities – as a Southerner and an unconscious Northerner – hit me like a ton of bricks. I had a sudden understanding walking down 10th Street that this is where my parents came from.

Although my father was generally uninterested in sports, my mother was a passionate Yankees fan, and they became devout followers of the UNC basketball team. While I never went to a synagogue growing up, I learned a lot about character through Dean Smith’s leadership. Coach Smith demanded that his team play with integrity, instituting traditions like having a player who got an assist point to the person who passed the ball, a practice that was later adopted widely within the sport. The community was united around the basketball team, and that contributed to a sense of connection within the community.

While my father reveled in the cultural aspects of his Jewishness, we were not part of a local “Jewish Community”. There were a few other kids in town that I knew whose families went to synagogue and had deeper connections to the spiritual aspects of the culture. Instead, my father gave his attention to Jewish artists like Billy Wilder and Ernst Lubitsch, both reflecting the more comedic and intellectual aspects of the culture. As a kid, I was happy to avoid religious instruction, but I was often curious about ideas related to what might be best described as the spiritual realm. My father was disdainful of anything that smacked of religiosity, which perhaps made me more curious. As someone who has had an unconscious impulse to push against authority, this lack of religion in my early years is probably part of the reason I ended up as a religious studies major in college.

My father never talked to me about it, but I recently found out about the Kaunas Pogroms, a massacre of Jewish people in Lithuania in 1941. My father would have been 8 years old at the time, living with his parents in New Haven. Both of his parents arrived in the US as 9-year-olds, traveling separately from Lithuania after an earlier set of pogroms at the turn of the century. I have to assume that as news about the ongoing massacres filtered back to his parents, it must have had a powerful effect on the family. I can just imagine the anguish they felt – and the sense of powerlessness, loss, and trauma that affected both of my parents as first and second-generation immigrants in the US during World War II, the Holocaust, and the years of displacement and upheaval that followed. My mother, whose birthday was Dec 12, remembers being very worried that her 7th birthday party might be upset by the airport being bombed near her home in Queens just a few days after Pearl Harbor.

In the past few years, as I worked on a film about the relationship between mind and body in regards to health, I have become more aware of just how powerfully past traumas affect us. While my father was a psychologist, he was somewhat resistant to dealing with the trauma he experienced in his own life, and instead focused his attention on others. Unfortunately, we now understand that trauma is often carried down through our genes. In fact, the reason I went looking into the massacres in Lithuania was because I had an interest in finding out about things that might have affected me without my full understanding.

THE KLAN

A couple of months after that Klan March in 1987, I moved to New York City for college, and I stayed for nearly 30 years. I played in a band, made movies, got married, bought a house, and had kids. However, in 2013, my wife and I decided to move from Brooklyn back into the house I grew up in down South. My mother’s move to a retirement community prompted our re-location, but we had a lot of others reasons to move as well. Raising kids in the city can be complex and difficult, and not only did we have several films to finish, but I also was interested in a slower pace of life. I wanted time to take stock of the work I had done. Sometimes we move forward with such a singular force that we fail to adequately pay attention to where we have been.

It was a bit surreal at first to re-inhabit the space I had lived in for my first 18 years, but fairly quickly it began to simply feel like home. A couple of weeks after returning, I found those black and white negatives I shot at the Klan rally. The images were both mundane and shocking at the same time. The nearly 30 years since they had been shot had given them a new relevance and resonance. I scanned them, and shared a few, which led to a friend pointing me towards sound that was recorded that day by DJs on the college radio station, Jeff Robins and Brandon Uttley. My film making partner Suki and I made a short film using these photos and sound called “The Klan in Chapel Hill.” Making that short sparked the production of a full length film we completed in 2017, compiled from about 30 years of our protest shorts called “Working In Protest.” We had been doing a lot of short political documentation since 2011, but finding the images made us realize that we had work spanning nearly three decades, and by weaving them together we could create connections between the past and present. Starting that process, we had no idea just how direct those connections would become. “Working in Protest” starts at a protest against a Klan rally in support of Trump’s victory in 2016 and then flashes back to the 1987 short. It ends at Trump’s inauguration.

After finishing the feature we continued to shoot local political events as they took place and eventually that led to us compiling the work into yet another protest-oriented film called “The Commons“. This film documents a series of protests around a statue of a Confederate soldier on the UNC campus here in Chapel Hill. The film was a direct outgrowth of the work I did at the 1987 Klan rally: it focused on human interactions and the feeling of the events, rather than focusing in great detail on the deep context of how the events came to unfold. This work is also formally connected to the documentation we did around the Occupy Movement in NYC. However, in contrast to the work done at the Klan rally 30 years ago or the Occupy protest 8 years ago, the recent sound and images collected around the statue didn’t have time to settle – and emotions around the work are still very raw and visceral.

When I shot the Klan rally in 1987, the Internet was not publicly accessible and I had no way to share the images, so they sat in a drawer for years. Conversely, during the more current conflict, I shot events as they happened and got them online almost immediately where thousands of people viewed them locally. The work was done with two purposes in mind: as people who supported the idea that “the statue had to go”, we shot and shared the pieces to amplify the message of the protest. We also wanted to document the situation in a manner that would be useful in the future. Finding these older color Klan images reminded me of just how much value this work has years later. Without images and sound from the time we, as a community, have less visceral evidence with which to ground our understanding of the past – or to understand the complexity of its connection to the present.

The 1987 Klan rally was my very first “shoot”, wherein I set out to document an event. I found these color images of the Klan rally when I was scanning images I shot shot two year earlier, a series of street photos in malls across the US. I imagine I must have shot the black and white images at first, and I grabbed these color shots after most of the cars full of Klan supporters had left. Only a couple of them have the kind of “action” that makes them feel urgent. However, collectively they create a more in-depth sense of what took place in that space after the rally, when tensions were still quite high and the police seemed intent on keeping the protesters away from the Klan members. In other words, the police, in their role of “keeping the peace,” appeared to be providing protection to the Klan.

I was a very active photographer in high school, contributing to the newspaper and the yearbook. Still, this was the first public event of importance that I approached with the intent of documentation. Once I got to college, I took a couple of classes in the art school and completed a few projects, including a project on an informal flea market at Astor Place and a book about the band Antietam. After finishing the aforementioned mall project, I started a band and began photo-documenting the underground music scene. I was drawn to being a part of that music scene because it was a Do-It-Yourself culture that turned its back on the record industry and the expectations of that system. It was a community that asked the kind hard questions about systems that had always resonated with me.

After graduating from college, I met my future partner Suki. She was focused on film production and theory. While I hadn’t studied film in college, many of my friends were in film school so I got a good deal of second-hand education. Shortly after we met, Suki assisted the director of the independent film “Party Girl”. Our colliding paths, and her relative wealth of experience and knowledge, led to our making a film together called “Half-Cocked” about the underground music world. Suki came out of the film world, while I came out of the world of photography and documentation. We combined our interests and made a hybrid film documenting ’90’s music culture within the conventions of a fiction film. However, its hybrid nature didn’t easily fit within the expectations of the film system of the time. The film wasn’t directly connected to the the experimental film scene and it wasn’t really a Hollywood film, or even an indiewood one. We found it more possible to distribute the film via the music community, taking it on tour and screening in rock clubs. We made one more music-related follow-up feature and then started making documentaries. Since neither of us came from a “documentary” background we had a hard time getting these film to fit within the expectations of that system. Our films also became increasingly political in nature over time. That work really ramped up around Occupy in 2011, and led to the production of “Working in Protest” and “The Commons.”

Completed in 2019, “The Commons” focuses on protests that took place in the common space around a confederate statue on the UNC campus. Interestingly, the cover shot for the Klan short (above) displays the start of the 1987 Klan march, which headed directly towards the location of the statue. While shooting these images in 1987, I remember feeling like I was documenting the last gasp of the Klan. However, there are aspects about what took place that day that are strikingly similar to what transpired over the past couple of years around the statue. As can be seen in the photo above, the cops look as if they are protecting, or even leading the march. Further, they seemed focused on protecting the Klan members from protesters, allowing them to leave in a way that feels very reminiscent of the police escorts provided to Confederate protesters as they retreated to their cars last Fall. There is currently very deep anger locally about the ways in which the police protected the supporters of Confederate ideology and criminalized those who protested the statue. There is also direct evidence that some of the police actively support white supremacist organizations.

I entered school shortly after desegregation and I believe that some effort was made to shield all of the kids from the divisiveness of the issue. However, the dividing line between elementary school and Junior high illuminated issues surrounding both race and prejudice against Jews. When I was younger, I was only vaguely aware of being Jewish. I didn’t get a lot of direct “anti-semitism” growing up, but felt a bit like an outsider in ways that I could’t articulate. However, in Junior high I got kidded a lot for being a “cheap jew”. It was true, I was cheap, and I was also increasingly aware of the cultural aspects of my family life that were different than that of my friends. I was the only one with the big book of Jewish Humor on my coffee table.

Feeling a bit like an outsider growing up had an unconscious impact on the way I engaged with the world. As a photographer I was drawn towards work that only hinted at the presence of the person behind the camera. My photos were more observant than interactive or stylized; I wanted the camera to go unnoticed and tried to disappear into the work. While I don’t think I could have articulated this thought at the time, I had the goal of shooting without judgment, wanting an unfiltered portrayal of my subjects. Those goals have continued to drive my work today. At protests, I see great value in having people like myself function as archivists, performing the important task of preserving aspects of the event so that others might have the tools to get a more complex understanding of the situation at a later time. I’ve also found that this kind of work has great value in the present.

When one makes work as part of a system – or teaches in a system, or governs through a system – that system provides access to resources, connection, and community. At the same time, those systems create a powerful limiting effect on language, awareness, and insight. Those who are part of a system rarely challenge it with much strength because to do so threatens their position and status within that system. Further, systems create a space for hierarchy and levers of power. As people move through the ranks of those systems, they become more reliant on them, and even less likely to challenge them. As an example, if you are in graduate school and want to find a Ph.D. advisor, you aren’t going to propose a thesis that challenges that advisor’s work. Instead, there is an unconscious pressure to suggest a thesis proposal that expands the line of inquiry rather than challenges it. This has a limiting effect on the kind of inquiry that takes place in that setting.

A lot of our work as filmmakers is subtly focused on highlighting how systems often lead to a kind of willful blindness – an inability to see things that are obvious to people outside of the system. In her book “Willful Blindness”, which focuses on this phenomenon, Margaret Heffernan uses the futures trading company Enron as an example. Almost everyone who worked at the company knew on some level that the accounting didn’t add up, but because full awareness of this truth threatened their livelihood, they found it almost impossible to see what anyone who came in from the outside saw clearly. When the house of cards fell it also became quite obvious to the Enron employees, many of whom lost everything.

I had a history teacher in high school. Mr Hickman, who often challenged the “liberal” perspective of the local students by asking questions that hinted at complexity. He liked to point out how history books often shrouded the truths of those who lost battles, and he forced us to think broadly. His class could get quite contentious, but he always stayed calm and never let things get personal even though high school students, like myself, could get a bit dogmatic. I give him a lot of credit for helping me to develop some ability to think critically while working to not be overtly critical, or judgmental.

When I shot these Klan images, I certainly had nothing but disdain for the Klan, as did the vast majority of my neighbors in town. However, when I went out that day, I wanted to capture the images in an observant way rather than a judgmental one. I wanted the reality of the situation to speak for itself.

MALLS

As I’ve said, I wasn’t religious growing up, and while I was drawn to classes in sociology and anthropology, I had no interest in going into either of those fields as a professor. Still, when I decided to shoot my project in malls, I thought as much about about these sociology-based ideas as I did about the work of photographers whose work I loved. About 10 years ago, when I re-discovered my mall images and they went viral, I came to see the deeper value of work that is non-judgmental. Unfortunately, this kind of work draws less attention to itself in a way that makes it easily dismissed as mundane in it’s time. This kind of work often feels both obvious and anonymous because it doesn’t call direct attention to the eye or the views of the person capturing it.

When I returned from my mall trip, I was excited by the work and quickly brought the slides to a photo gallery in NYC. The person at the gallery glanced at them briefly, almost chuckling. She wasn’t the only one. The general response was, “yeah, it’s people in malls, so what? Malls are awful.” Part of the “problem” with the work – that it wasn’t sharp enough, or critical enough of the situation – is what gives it even more value now. Thirty years later, the images resonate with people deeply, and they go viral repeatedly. If you search for malls 1989 on google and hit images, they are essentially the only images that come up. The response to these images cemented my sense that work like this may not have as much value in the moment, but that the value of the work grows exponentially over time.

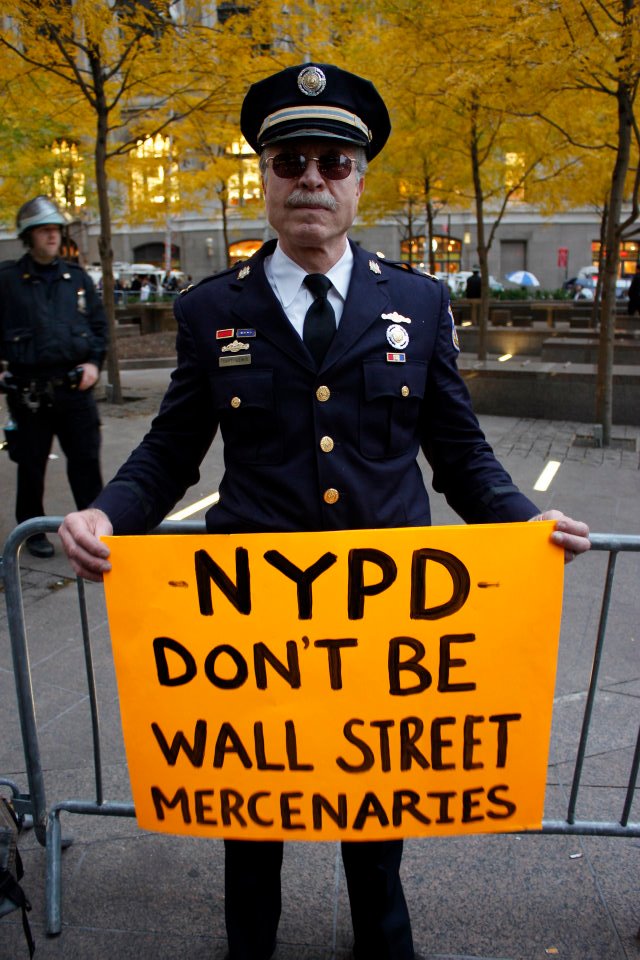

OCCUPY

It was about a year after re-discovering the mall images that we started to shoot at Occupy in Zucotti Park and I tried to bring this same kind of middle-space sensibility to that work. I was first drawn down to the Park by the advocacy-oriented videos I was seeing online. I also saw some of the news pieces which made me want to visit in order to understand what was going on for myself. When I got there, I found dozens of people holding signs, ringing the park. Others were talking to them to try to get a sense of what the demands were. I started to photograph and film the scene. As I circled the park, I found that many people who had been asking questions were now holding signs. I asked them why they were there, in order to both present that as a video right then, but also because I understood the import of documenting historical events in real time.

At the time I grappled with the importance of – and issues with – documenting from an advocacy perspective. The advocacy-oriented work done in support of the Occupy movement got people interested and invested in the movement, and this built an increasing sense of momentum. While I personally appreciated and was inspired by that work, I also believed that the kind of documentation we were doing was also important. For those who might be skeptical, less advocacy-oriented work makes more room for inquiry. Further, years later, advocacy work often feels dated and less present, leaving the more observational work with a different kind of value going forward. Again, this is something that I picked up from my experience with the mall images. Work about malls made at the time, that tried to play up the stereotypes or overtly highlight the trends of the time, feels affected and less convincing than the simple observant images.

“WORKING IN PROTEST” and “THE COMMONS”

It was a couple of years after doing the Occupy work that Suki and I moved to North Carolina and continued to make shorts about political events. That work formed a bulk of “Working In Protest“. In addition to local events, we filmed at the Democratic National Convention and the Inauguration. The film begins at a North Carolina Klan march in Dec, 2016 shortly after Trump won the election. It then flashes back to the short that we made using the black and white images from the Klan march in 1987. We showed the film at festivals around the world, but it didn’t garner much attention. Audiences absolutely appreciated it, but since it wasn’t really the kind of protest film that an advocacy group could champion, and it wasn’t arguing for some point of view or following specific characters, it didn’t have a channel or outlet by which to promote it. It’s not just our political narratives that have become more fractured and structured. These issues of compartmentalization and identification stymie all kinds of work and processes.

As we wound down our travels with “Working in Protest,” the chaotic events in Charlottesville took place. Those events inspired protesters in Durham, NC to tear down a Confederate Statue. A few days later, there was a rumor of a Klan march in protest of that action, so I headed over to capture the action. The Klan didn’t show, but thousands of counter protesters did, and I was able to capture some interesting interactions. We quickly made a short film about the events of that day and put it up online where it was widely viewed locally as the independent weekly shared the link.

A few days later, on the first day of classes at UNC, students and community members gathered to demand the removal of a Jim Crow era statue called Silent Sam. Events turned quite violent with a very aggressive response from both campus and town police. As with almost all of the previous work, my camera was one of many, and I did nothing to interact directly with the protesters. I did not interview anyone, and I tried to stay out of the way. I stayed up all night in order to get a piece up the next day. Again, this piece was widely seen and we got a lot of appreciative feedback.

I then went to shoot at a sit-in that students were holding around the statue and filmed a conversation between student activists and a local man and his daughter. I didn’t edit that piece, and decided not to film anymore because I didn’t have an interest in shooting a long-term, longitudinal documentary about the protest movement. A few months later, I saw a tweet about a film being made in a class at UNC. We contacted the tweeter and offered them all of the footage we’d shot so far for them to use in their film. Their professor came by a few days later and picked it up. When we didn’t hear back from them, I checked in and found that they were having a screening. We went to see the film and it was a well-made primer on all the important context related to the fight over the statue that had some really interesting creative sections as well. They hadn’t used much of our footage, but we were glad we had the opportunity to support their work.

The next fall, the protests started on the first day of school. I filmed powerful speeches by the student leaders and was there as activists tore down the statue. Once again, I stayed up all night and got a piece up by morning, and it was shared widely. The response to the work was very enthusiastic and I began a long communication with the Facebook page for the group, called “Move Silent Sam.” The admin for the page expressed great support for the work and told me that the group was very appreciative of the piece. They asked if I could share my footage with Democracy Now, as one of the protest leaders, Maya Little, was going to be interviewed. She had spoken before the statue came down and the show used some of that footage as well as the general protest footage. About a week later when Confederate activists came to protest the statue’s removal and anti-racists gathered in response, I introduced myself to Maya and explained that we had made the short “Silenced Sam“, and that I had given our footage to Democracy Now. She thanked me, but things were hectic and we didn’t really get to talk. At the next protest, I met a Facebook friend of mine in person for the the first time. He did much of the event planning for the group and he began to make sure I knew about the various protests by inviting me via Facebook events. As with Occupy, my personal sensibilities were in line with the protesters, but for reasons expressed above, I did not become “a part of” the protest group. As with that previous work I wanted to create something that would give people access to a sense of being in that space so that they might be able to make some sense of it themselves. Media tends to explain (though the video work being done by the local newspaper was very strong), and activist work tends to push a specific narrative. While I tend to agreed with the narrative being pushed I have a concern that this work doesn’t make space for people not already engaged in the ideas. I personally feel alienated by work that is propagandistic in nature, and it makes me less likely to engage. I tend to make work that tries to leave space for people to view it from their own perspective. This can be confusing to people, especially in this cultural moment, which is so divided.

Over the next several months, I filmed a half dozen protests and Suki and I edited them and put them up for people to view. I met a lot of people who had seen our pieces and their encouragement made me want to continue doing it. In early November, we realized we might be able to put these pieces together to create a narrative similar to “Working In Protest”. Our first pass at a longer-form film was a bit heavy at times. It was mostly shot in fairly confrontational settings so we struggled to figure out how much context to include. Having spent a lot of time documenting protests over the past 30 years, we were interested in translating the feelings and rhythms of the events more than the specific context, so we also tried to weave in some of the down moments as well. When one goes to many protests, they start to blur together and in some sense that’s what we thought the film should feel like, an it was unsurprising that it would feel a bit exhausting to view it. While it wasn’t yet working, we saw that it was something we could continue to shape and expand.

A few days after coming up with the idea of a longer-form film, we took our short “Silenced Sam” to the Cucalorus Film Festival in Wilmington, NC. We were surprised to find that the student-led collaborative film “Silence Sam” that we had shared our footage with, was playing before our film in a block of shorts. It was much more developed than the previous version we had seen. In this later cut, it included three of the scenes we’d shot. This included the scene we had shot at the sit in after the first major protest we shot. It also had a couple of quieter shots that the filmmakers had gathered that we thought might be useful in our film. Though it was billed as a work in progress screening, none of the filmmakers were at the festival. We wrote to the professor whom we had given the footage to in order to compliment them on their work. We explained that we had started to make our own film, describing it as being more about interaction in the common space than about the direct issues of the statue. We had settled on the title “The Commons” because we wanted it to take place entirely in that common space. This created some difficulty in terms of providing enough context to understand where we were and what was going on, but no so much that it would become directly about this specific series of events and the competing narratives that were taking place. We shared a link to the rough cut of “The Commons”, and said that we’d love to be get a couple of shots from their footage if it was possible. The professor responded with enthusiasm, “Hi Michael, that’s great to hear that both the films are out in the world and having impact!” She added that she was no longer at the university but would reach out to the students. We didn’t hear anything back, so Suki sent a note directly to the filmmakers asking for the specific shots. After a little back and forth, we were told by the director of the film, Courtney Stanton, “Thank you again for your patience. Unfortunately, our impact producers and crew did not feel completely comfortable lending out that footage. That footage was pretty sensitive and specifically entrusted to us to look after. Not enough of us were comfortable handing it out. We apologize for the inconvenience and thank you for understanding.”

In the meantime, the response to our rough cut was very strong and by mid December we had already been invited to several festivals. We figured that, as with “Working In Protest”, a few festivals would play it, and it wouldn’t make much impact. However, to our surprise, a very important festival, “True/False,” invited the film to play there in early March. A few weeks earlier my mother had gotten very ill and I spent 4 nights in the ER and ICU with her as she fought severe pneumonia. While I slept there, Suki rushed to get the film ready for the festivals. About a week before we finished, we heard on the news that the Chancellor of the University was stepping down and ordered the removal of the concrete base of the statue. I rushed home to get my camera and again was one of many cameras as protesters celebrated, gave speeches, and the base was removed. We had already sent the film off and had to re-edit the ending now that it was more final. In many senses, the film, while not clearly “experimental”, was an experiment. While we had projected much of our protest work, it was often years after having shot it. In this case we’d be projecting the film within months of shooting much of it, and without having done many test screenings. We set up a screening for the activists through the person who had coordinated all of the events for the group on Facebook. He assured me that he would invite them all, and cancelled the first attempt because many were going to be going to a different screening. However, when the activist screening took place only a handful of people came. Their response was positive.

However, in the end, the director of “Silence Sam” and her professor, as well as some of the activists who appear in the film are distressed and angry about our project. At the True False Film festival we had two well received screenings. At the final one we were met by a protest led by the “Silence Sam” director Courtney Stanton. She and her colleagues, who were part of a de-colonize documentary fellowship, expressed that they view our work as colonizing and feel that as people who were outsiders from the movement, who did not involve them in our work, we had no right to make our film. We have worked to address their concerns and pulled the film from many festivals in order to make some space for dialogue. We hope that, as with our other films, viewers will judge for themselves about the value of the film and our larger project of film-making in relation to protest. Over the course of 9 films we have worked to highlight important ideas that drive conversations.. As stated, we had shared much of our work with the student filmmakers to use, as well as publicly shared almost all parts of the film as we made it, and those had been very positively received, so we were surprised at the reaction to the finished film. Further, it wasn’t a film about the movement, but instead more about the idea of the contentious “moment” we are in, and how that plays out in public conversation.

Finding the color image of the Klan rally re-connected me to the reason we shot the short pieces that we did, and why we then edited those into a feature film. I believe that when we go out in public to protest in the commons, we do so with an understanding that we are adding our voice to a public conversation. In that space, we all play different roles. Some people are leaders, some are supporters, some are resistors, and some are controllers (i.e. the police). I see my role as a documenter. Over the past 30 years, most of my work has not been seen as valuable in the moment. This can be frustrating, and even overwhelming at times. Making work that exists at the edges of systems in ways that don’t conform to the expectations of those systems, often leaves that work unseen. Given that reality and our previous experience, we had no expectation that “The Commons” would do more than play a few small festivals, and that is all that it did. Still, we felt it was important work to make, so we made it anyway. Our experience showed us that, like these 1987 Klan images, or the mall images, the real value of the work would reveal itself in the future. Over the past decade, I have watched as the older work gains clear social value over time.

It is my hope that as time passes, people will see the historical value of this work, as well as its current value in highlighting the level of division that roils our country. Almost every person we’ve talked to about the film has found it unsettling, but most have also communicated that they understand that the work of the activists in the film is heroic. We believe so as well.