07 Jun Consciousness, Framing, and Balance

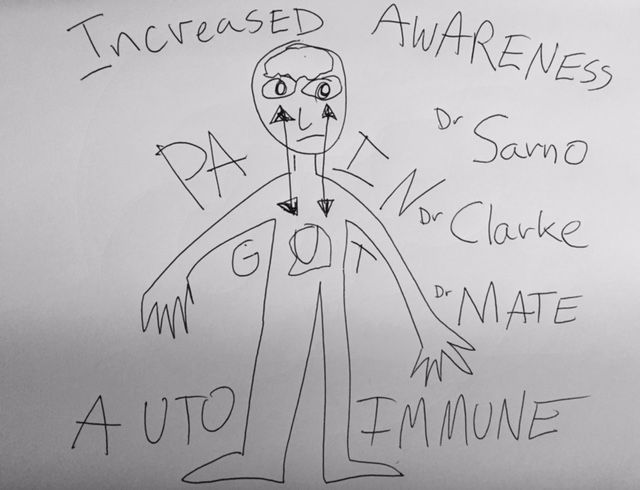

In 2004, when we set out to make a film about Dr. Sarno, we couldn’t have envisioned the movie that it has become. Over the last 10 years there has been a dramatic shift in the level of acceptance of the mind body connection in terms of health care. When we started trying to talk about the connection between emotions and pain, we met great resistance. Now most people seem to accept the basic connection. The good thing about working on the film so long is that this shift can be felt in the footage.

Before making documentaries, my partner Suki and I had made a couple of films that were a hybrid between fiction and documentary. We crafted narratives that documented the underground music scene that we were a part of. I had taken a few classes in film theory and a few photography classes in college. After school I focused on playing in a band, and met Suki through a musician friend. She had moved to New York to attend graduate film school at NYU. Shortly after meeting her I suggested that she drop out and make a film with me about the people I had met in the South while on tour with my band. She had met them herself when she went on tour with her roommate’s band and agreed. In some sense, we believed that because we were a part of the world we intended to document, we didn’t have the “critical distance” from it to create a “documentary”. From my anthropology and photography classes, I had internalized idea of what was “allowed” in terms of documentary and felt compelled to step outside the form even as our main goal had been to document something that we were a part of.

After making two feature films about that world, we stumbled into making a documentary called Horns and Halos – a largely verite film that focused on an underground publisher and author who were trying to re-release a discredited campaign bio of GW Bush. While we still held on to the idea of keeping a “critical distance” from the subject of our documentary, it was a very immersive film that followed the main character closely for a number of years as he and the author faced numerous obstacles in their struggle to get the book out. This gave us a structure to frame the film around. One of the challenges we faced in making the was that our world views were somewhat aligned with those of our characters and so the film could easily become something that those outside the viewpoint of the film could easily dismiss, especially if it challenged their beliefs. We took great pains to have the film be as honest and critical as possible. In the end, this made for a stronger film that holds up over time. However, in an increasingly partisan environment, it confused people who expected it to be more strident or argumentative. People who hated George Bush wanted a film that tore him apart. Those who were in support of the administration took us to task for not taking a more critical viewpoint of the author – who had a checkered past – and the publisher. The film was called “Horns and Halos” because it was about taking an open look at our gifts and our flaws.

We envisioned a similar process, as well as similar hurdles, when we set out to film about Dr. Sarno. He agreed to let us film after he saw Horns and Halos, and understood what we aimed to create. It was likely that stress related to self-distributing that film (coupled with the pressures of starting other unfunded films while also struggling with the demands of an infant daughter) had led me to have the debilitating back pain which delivered me to his office in the first place, so there was a certain irony in the fact that we were going to try to do the same thing again. We imagined that we would follow Dr. Sarno as he saw patients and worked to push for his ideas in the world. Unfortunately, ethical considerations kept him from introducing us to patients. He was also not interested in fighting to get his message heard. As he points out in the film, most people aren’t open to the idea that our emotions might be responsible for pain, and if they aren’t open to it there’s no point in arguing. Even when his book “The Divided Mind” was released about a year into our filming process, there was no book release event, or even any press for us to capture. Despite the success of his earlier books, “The Divided Mind” got no attention whatsoever when it came out. We didn’t have a character to follow in the way we had expected, and we couldn’t figure out how to move forward. Our plan had been to film events and make a story out of that, but we had no events to film.

Dr. Sarno’s books had saved my father from years of excruciating pain, and my brother had gone to see him which had set him on the path to healing from crippling hand pain. I felt a great responsibility to make sure if we made a film, that it be a great one. After applying for a couple dozen grants and coming up empty, we were stuck. Reluctantly, the tapes went in a drawer and we concentrated on other projects, including Battle for Brooklyn. This was the main film we were working on when my back went out in a big way for the second time.

When we completed Battle in 2011, the struggle to get it out into the world took a major toll on me emotionally, and my leg pain came back with a vengeance. Despite what I had learned from Dr Sarno about how the stress was causing my pain, it got steadily worse. I was reluctant to reach out to him for help because I felt so badly about our inability to get the film project off the ground. I should have called him though, because the pain spiral got worse and worse until I was eventually thrown out of my chair while writing a email. When I hit the ground I screamed, “Get the camera”, because I knew that we had to make this film, and that we finally had the character, me, to lead us through the story. That was 4 years ago and we are finally in the process of putting all of the pieces together.

The film is still very much about Dr. Sarno, but the world has changed dramatically since we began our quest 11 years ago. The scope of the film has expanded substantially as well. When we started, we could find very few people in the mainstream medical community who were speaking as powerfully about the connection between mind and body. However, in the time that we had been unable to make the film, not only had similar books been published in other fields, but a veritable flood of studies that illuminated the connection were beginning to garner attention. We are trying to weave this narrative -of a changing world- into our film.

Act 1 of the film relies heavily on those first few tapes that we shot between 2004 and 2007, and focuses almost entirely on Dr. Sarno and his work. This act comes to and end in 2007 with a clear pronouncement of Dr. Sarno’s skepticism that his ideas will ever be embraced. Act 2 begins with me screaming on the floor, and focuses not only on pain – and Dr. Sarno – but a host of other doctors who make the connection between health and emotions in general. In the five years that we were unable to make the film the pain problem had exploded and other practitioners had begun to question the absolute stranglehold of the bio-technical model of medicine. Act 3 takes an even more expansive perspective and looks at the broader implications of how individuals and groups interact with each other and themselves, and how that might affect our health. However, Dr. Sarno’s story continues to be the thread that holds it all together.

We have been editing in earnest for the past 6 months, and Act 1 feels solid, giving us the foundation to move forward. We have been shaping, dismantling, and re-shaping Act 2 of “All The Rage” all week as we try to figure out the tone and flow of information. This morning we paused to take a look at our interview with Dr. Andrew Weil. We found so many strong clips that I was compelled to call him the Babe Ruth of interviewees; he hit just about every line out of the park. It may seem counter-intuitive, but the lines are so strong that they almost don’t work because they are so obvious and definitive; they all feel like they end the scene. Working with this footage inspired us to think even more deeply about the ideas that are central to the film. We’ve been so focused on the details that it felt like we needed to take some time to think about it from above, from outside the bubble of the film.

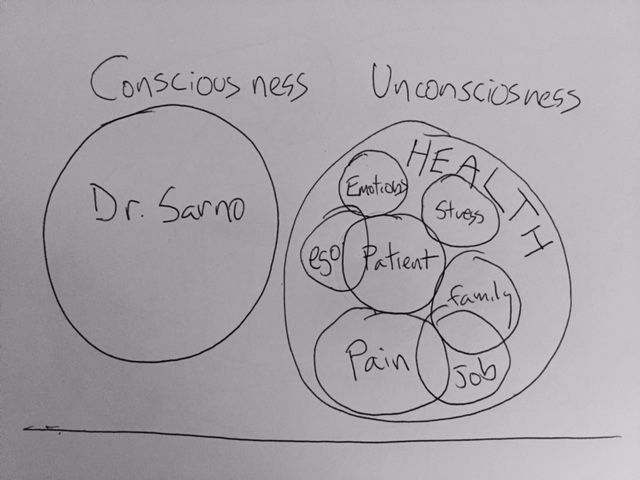

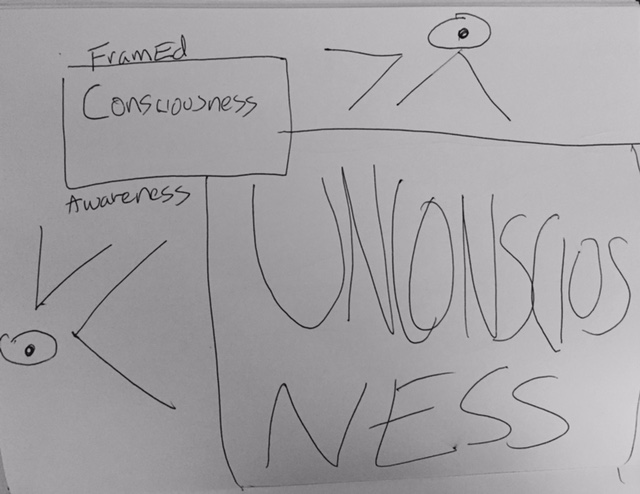

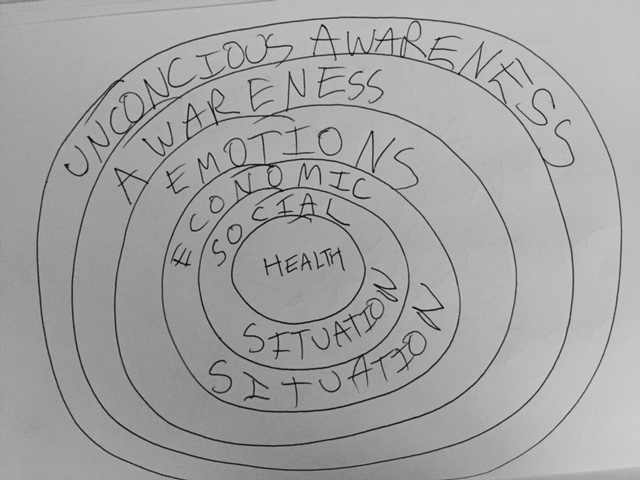

While the film is very clearly about the relationship between mind and body in regards to pain and other illnesses, the subtext (which involves several different thematic threads) is much more complex and difficult to articulate. The three main intersecting themes that were discussed today are the line between conscious and unconscious thought, framing, and balance. As we talked, it became clear that the balance between consciousness and unconsciousness on the individual level, the family level, the community level, the social group level, and the institutional level – as well as how these groups interact – is central to our story. Further, the way these different subsets frame their relationship to themselves and the other groups is key to understanding the way in which ideas move through the world. In some sense, framing is simply a way to describe the structure of our conscious thought, and yet this framing is shaped by a myriad of unconscious assumptions and patterns. Being able to step outside that frame and view it in a conscious way is essential to understanding ourselves and our assumptions. As filmmakers whose beliefs are in line with our main character, we have to be very aware of this line because if we are not, we risk alienating anyone who does not already share this worldview when they start watching the film.

This idea about framing also intersects with ideas concerning media and science and how different groups respond to -and interact with- them on both conscious and unconscious levels. People who see the world through a specific frame tend also to consume media that supports that frame. For example, people who align as conservative thinkers tend to watch Fox News and read the New York Post, while “liberals” read the New York Times. Our alignment with these groups leads us to look less critically at those media sources we align with and dismiss those whose ideas do not comport with our own. This same idea can be seen when we look at different fields of science. People who are trained in a certain field or discipline tend to respect the rules and ideas of that group while often dismissing the practices they do not understand. The old saying goes, “If your only tools is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” Further, if you are skilled with using a hammer you are likely to dismiss the efficacy of other toosls. In an interesting scene from John Stossel’s 1999 20/20 piece on Dr. Sarno, a surgeon at NYU Medical Center compares going to see Dr. Sarno with swinging a cat around one’s head in a cemetery. Here we get a nice mash up of media and scientific framing.

In Act 1 the film focuses on Dr. Sarno and his relationship to his patients as well as their relationship to themselves and the world.

When we took a look at the structure of the film, we could see that Act 1 is very much about these issues on the level of the individual as the film focuses on Dr. Sarno, and how his ideas are dealt with by his patients and by people who have read his book. There is some discussion about how the patients deal with their community as well as how Dr. Sarno interacts with the medical community. However these are dealt with in a much more robust manner in Act 2. As discussed above, in Act 1 we also deal with how Dr. Sarno’s ideas have intersected with the science/medical community and the media. Essentially, he was ignored by both of these groups (the John Stossel piece is one of only a handful of media appearances over 30 years), yet his work began to spread widely through his book and word of mouth. We often think of media in terms of journalism like TV and Newspapers. Books are a slower, more in-depth form of media communication that have even more resonance. A quick look at the reviews on Amazon are clear evidence that the book resonates with people.

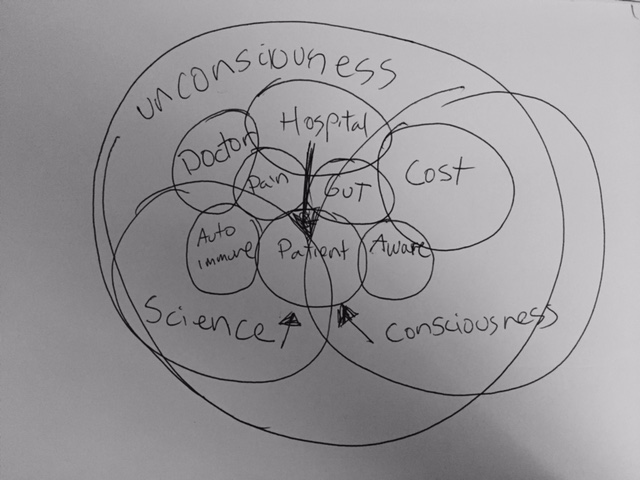

The focus expands to health care in general and how the doctor patient relationship affects health and healthcare practice.

In Act 2, the focus of the film expands considerably. My status as a patient/character becomes more pronounced and my interactions expand beyond Dr. Sarno to include a host of other doctors. In Act 1, Dr. Sarno talks about becoming conscious of the how powerfully the mind body interaction affects health. Armed with this knowledge he was able to re-frame the way he looked at his job and bring a more balanced approach to his practice. He was also able to help his patients become more aware of how their unconscious actions and thoughts affected their health and to guide them towards bringing more balance into their lives. In Act 1, the central conflict is Dr. Sarno’s effort to make people more conscious of their own feelings and how those feelings impact them personally. In Act 2, the process expands as a host of other doctors work to do the same within their own fields. This combined effort – as well as social trends – leads to a general increase in awareness and acceptance of the idea of the mind body connection. In fact, this shift has been so profound and so swift that it can be felt through observing the footage.

Further, while Dr. Sarno recognized right away that he was dealing with a process that affected more than just pain syndromes, he kept his focus on pain in order to frame the message in a way that people could hear it. There was so much cultural resistance to his ideas that he had to be direct and powerfully persuasive in his approach. He found that if people had trouble “buying”/believing that their emotions were the primary causative factor in their pain syndrome, that they were much less likely to heal. This issue still exists in Act 2 but the film, like the cultural awareness, begins to expand and illuminate how stress and repressed emotions affect the whole body.

In Act 3, the area of inquiry expands beyond the doctor/patient and doctor/healthcare system relationship to that of the individual’s interaction with society as a whole. We will examine the broader economic, religious, belief, and social structures at play in the situation.

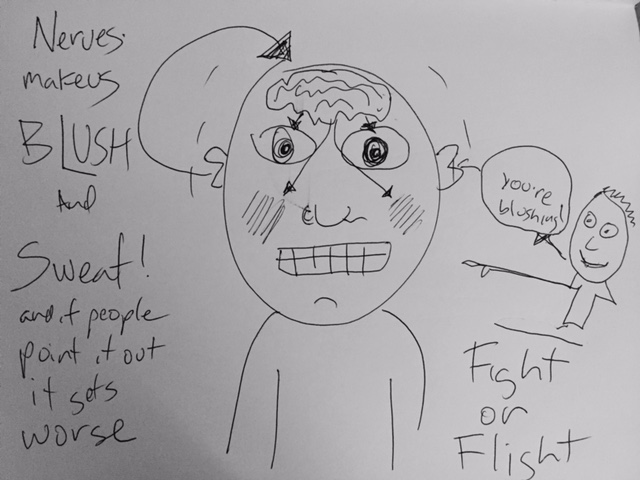

In Act 1, we can see that despite cultural resistance to dealing openly with our emotions, it is simple enough to grasp that when we have an emotional response to a situation or event, we also have a physical reaction. That physical response is often unconscious and automatic, seemingly beyond our control. For example, blushing, or sweating when we are nervous, is not something we have much control over. While most people don’t realize it, pain can also be an unconscious physical response to stress or anxiety. Often these physical responses can create feedback loops that accelerate the effect. For example, when someone blushes or sweats when they are nervous, and it is pointed out to them, they might blush even more.

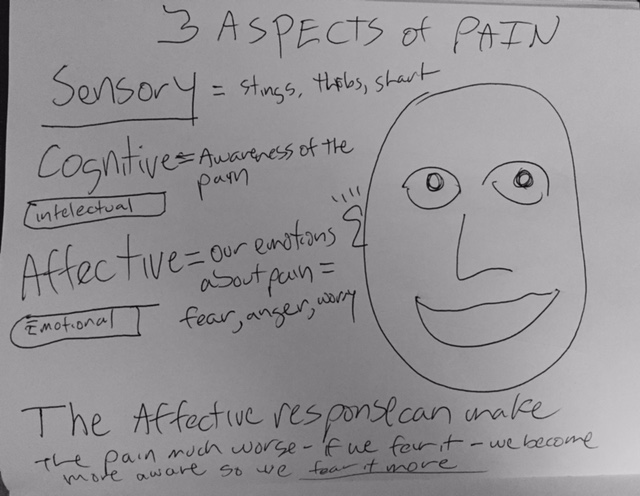

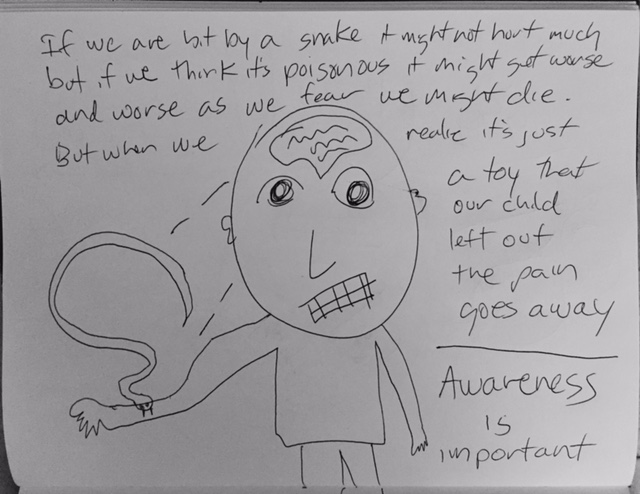

Dr. Schubiner in his book, “Unlearn Your Pain,” discusses the idea that pain has both physical and emotional aspects which he delineates as sensory, cognitive, and affective components. We use the term sensory to describe how it feels; it might sting or be described as stabbing or throbbing. Pain also has a cognitive aspect in terms of our focus on what is causing it, how long it might last, and whether or not there is something to be done about it. The third aspect is the affective component, which consists of our emotional reaction to the pain; which is often based on our cognitive assessment. If we think of the pain as something dangerous, or fear that we might have it for a very long time, then we are likely to respond to it with anxiety.. He points out that these three aspects are processed in different areas of the brain yet they are intertwined and affect each other.

Our consciousness of each of these aspects has a powerful relationship to each of these components and how they interact. For example, the more conscious we are of the sensory response, the more likely it is that our cognitive focus will increase, which also means that our emotional response will be more intense. This is where we can begin to focus on how we view the world around us, how we frame things. If we are anxious and respond to pain as something to fear, we might be even more conscious of it, which in turn might increase its intensity. In this scenario, the more attention we pay to the pain, the more likely it is for it to get more intense, which in turn might make our emotional response more negative. This is likely to increase the sensory response which amps up the cycle, creating a feedback loop that makes the pain louder and more powerful. If we feel trapped in the cycle, the neural pathways of pain become even stronger.

Awareness of this process can help us reverse it. As Dr. Sarno points out, his prescription for mind body pain syndromes is knowledge. In this case, uncovering the often invisible/unconscious frame of how we respond to pain on all the different levels gives us the awareness we need to take control of our response. The response matters, and we do have the ability to change our conscious response to situations. It’s not easy but it is possible. When we become aware of the frames through which we view the world, we have even more power to adjust them. In addition to Dr. Sarno’s books, other books like Dr. Schubiner’s “Unlearn Your Pain“, Dr Eric Sherman and Frances Sommer-Anerson’s “Pathways to Pain Relief“, Steve Ozanich’s “The Great Pain Deception”, Dr Schecter’s “Think Away Your Pain“, and Nicole Ferber Sach’s “The Meaning of Truth” all provide a number of tools to help people change their frames and bring more balance into their lives.

By the end of Act 1, it should be pretty clear that our emotions have a powerful effect on our response and relationship to the world around us. When we see danger all around us, even in ways that we aren’t fully conscious of, our body will constantly prepare us for fight or flight. However, this constant level of stress creates physiological changes that can often lead to pain and other illness. In “Unlearn Your Pain”, Dr. Schubiner, like Dr. Sarno before him, gives people tools to increase their awareness of what’s going on, as well as a plan to use that knowledge to change their reactions on both conscious and unconscious levels.

At another point in his book, Dr. Schubiner points out that our brain processes approximately 11 million pieces of information a second, but only about 40 pieces of that information is held in our conscious brain. While we know that many of our bodies’ functions – like our heartbeat and our breath – are automatic, we also have some ability to control them as well. Actions like lifting our foot to walk or throw a ball are learned, but become unconscious acts through repetition, or practice. If we had to spend conscious energy lifting our foot, or coordinating the actions needed to throw a ball, we’d never get anything done. The same process is true of very much of our decision-making.

In order to make decisions, we often default to assumptions and patterns of behavior. We group things for efficiency. If we noticed the complexity of every leaf or blade of grass, we’d have a hard time moving. If we looked through every box of cereal in the store… If we didn’t group people into subsets, it would be hard for us to function in society. However, this same process that allows us to move down the street without getting to know each person we pass, leads to the unconscious frames of racism, classism, and sexism. Scientists are increasingly discovering evidence that our brain creates channels just like a river system. Thoughts flow down familiar pathways, and the more we think these thoughts, be they negative or positive, the deeper those channels run. Just as we can damn a river and create new channels, we can change the patters of thought in our brains. If we spend a little bit of time unpacking how our assumptions and ideas have formed, not only about how we view the world, but how we view ourselves, we can regain some control over these automatic responses.

When we take these same ideas related to consciousness and framing and apply them to the different groupings expressed above, things get even more complex. We experience the world on both an individual and a cultural level. Using the emotion of anxiety, we can begin to think about how an individual might respond to this feeling. Anxiety leads to a physical response like increased heart rate, shortness of breath, and a heightened awareness of danger. Sometimes we don’t even realize we are anxious until we feel these symptoms of the anxiety. When this anxiety becomes chronic, it often also becomes largely unconscious; it becomes a new normal that the individual is largely unaware of. However, the effects of this anxiety continue to affect the body even if we aren’t aware of it. When we are anxious we are often in a fight of flight state of body awareness. However in the modern world the threat that we face is often emotional.

If the anxious individual is part of a family grouping, we can imagine that all of the other people in the family feel the effect of that anxiety as well, and often respond to it in ways they aren’t aware of. Imagine this same person is in a fender bender, and their heightened state of worry leads to whiplash. Both Dr. Sarno and Dr. Schubiner point to a series of studies that show that both anxiety and the expectation of injury play a clear role in the development of the syndrome we call whiplash. For example demolition derby drivers don’t get whiplash. If the physical aspect of accidents caused whiplash then these drivers would certainly get it. When one person gets whiplash, or back pain, or fibromyalgia, It’s more likely that others in their community will also get these symptoms. This is called social contagion. If this person is not conscious of being chronically anxious, or that their anxiety might be a causative factor for their pain, then they will mostly likely have a negative affective response. In other words their sense of fear and resentment in reaction to the pain might increase which will in turn increase their focus on the pain which in turn has a tendency to increase the sensory awareness of the pain. However, helping the person to understand this process gives them the opportunity to unwind it.

The way that energy and ideas flow between individuals and within groups is relevant to the issue of pain but it also has much broader and complex resonance. When we look at how unconscious anxiety affects a family, we also can see how it affects a school community, a corporation, or a nation. When we dig deeper, we can see how the way we respond both consciously and unconsciously affects individual systems in a body. Perhaps the anxiety manifests itself most strongly in one person’s gut, and they get a terrible stomach pain. If their affective response is to think they might be dying, then the rest of their body is seized with anxiety and the problem gets worse. If they instead realize that the pain spiked because they ate a half-pound burger on top of unconscious anxiety, their anxiety will likely not increase. From a societal viewpoint, we often talk about the emotional health of an economy. If society is anxiety ridden about the future, people are unlikely to spend their resources and things get out of balance. If they are too optimistic and overspend, things can also get out of balance. How an individual – or a group – frames a situation, affects its response to it. We need a certain amount of stress in order to function, it drives us to protect ourselves and gather the resources that we need. However, if we have too much stress it can harm us. We need to find balance

In terms of the structure of the film the subtext of each Act deals with balance in different ways. We have seen that in Act 1 the focus is on Dr. Sarno’s effort to bring balance back to his practice and his patients. In Act 2 other doctors are joining in the struggle and there is an effort to bring back the balance between mind and body in the whole system. In Act 3, the focus becomes balance within society. One of the doctors featured in Act 2, Dr. Gabor Mate, is writing a book called “Capitalism is Killing us”. When we combine this idea with the research of Dr. Sapolsky who discovered that low status primates have lower health outcomes, and that of Dr. Nadine Burke Harris who realized that she was mostly treating the symptoms of stress in her high poverty clinic, we can begin to see how a myriad of factors affect our health. When Dr. Burke-Harris realized how powerfully the stresses of living in poverty affected her patients she looked for research that might illuminate her discovery. She quickly found the ACE study hiding in plain sight. This study in which 17,000 individuals were asked about 10 possible stressful situations that they might have encountered in childhood including, sexual abuse, parental divorce, parental death, etc. If they had 4 or more adverse events they were 4 times more likely to get cancer or heart disease.

It becomes clear that the key to health care reform is dealing with the problems on the individual level, on the healthcare level, and on the societal level. As people (patients), we need to become more aware of not only the idea of the mind body connection, but the connection between our own thoughts and how our bodies react to them. The health care system needs to give more power to patients to activate their own healing, and our society has to recognize how powerfully inequality affects us all.

We have some work to do. The first step is awareness. Then we move on to action.

Rameshwar Das

Posted at 03:53h, 26 JuneMichael,

Glad to hear All The Rage is moving along.

I can say my perspective and integration with my practice deepened from the interview I participated in with you and Ram Dass. More and more I see the unconscious as also a nova of spiritual energy and love, besides all the negative repressed emotion Dr. Sarno endeavored to bring to awareness as a way to treat suffering. Meditation and practice tap into that Mother Lode too. …It feels like the dark energy of the universe is also love. It’s all here.

Namaste

Rameshwar Das