12 Nov A Letter to Young Photographers

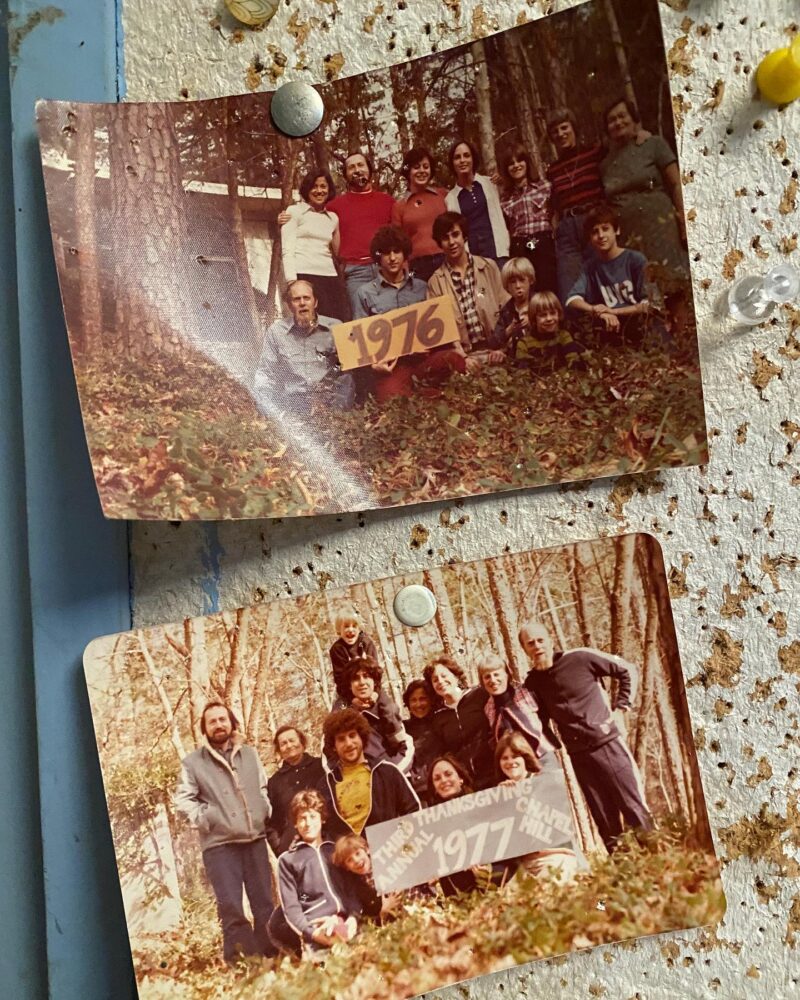

I’m an artist who has spent the past 35 years making music, photos, and films. As you might imagine, I have made a lot of mistakes in 35 years of making work. Some of those mistakes were necessary and useful. Some I repeated more times than I’d like to admit. I didn’t take a traditional route towards becoming a photographer/artist, so I probably made more “mistakes” than other people. I wrote this post a while ago because I wanted to share some thoughts that might help other people skip some of the mistakes. You’ll make plenty of mistakes without this advice but it might help you to think a little bit more clearly about goals and expectations. My daughter read through it and helped me to clarify one point; this advice is for people who are interested in making photography as art. There is absolutely nothing wrong with making photographs as a product, or for commercial purposes. She just made it clear that the focus is more about how to think about making photos that are more about self expression than sales. I have made photos throughout my 30 years of making art. I documented malls in the late 80’s. Then I documented the music scene in the 90’s. Over the next two decades I concentrated on making documentary films. I continued to make photographs, but for the past 20 years my focus was more on the films.

I first wrote this post about 12 years ago when I began to really go back through my messy archive of old photo work. Even though I worked on a lot of photo projects I never really worked professionally as a photographer (either commercially or as an artist), Much of the work I did was vaguely documentary in nature. While a lot of it was mundane enough in the moment to not seem worthy of much attention, that same mundanity seems to have given it a lot more resonance in the future. This has become increasingly clear as the years have passed. When I first wrote this my oldest daughter was 11. Now she’s 23 and studying photography and filmmaking. So, I’m revisiting it in order to provide some useful advice to her as well. I’ve also made an effort to make it less of a letter and a bit more direct with its advice. We live, we learn, and we change. I guess the first bit of advice is don’t be afraid to change. Right now you may be interested in one thing. Maybe it’s punk rock. In five years you might find yourself more interested in free jazz or opera. This doesn’t mean you turned your back on your roots.

Believe in yourself

I often think about advice that might have had a big impact on me when I was a young photographer. From the moment that I took a basic photo class in high school I knew that I wanted to spend my life making images, but I wasn’t sure what that might look like. While I really enjoyed it, and I got a lot of positive feedback for my photos, I did not believe that I had a truly special talent for it. My first bit of advice is don’t trust your self doubt. My winding path, which was often unconsciously steered by that doubt, kind of worked out, but it was sent off course via obstacles of my own creation. If you love photography keep loving it. Keep making images, and continue to hone in on what it is you love about it and why. I did that myself to some degree, but if I had someone to kick me in the right direction, whom I might have listened to, I might have made some different decisions.

Be organized

Make sure to be careful about how you store your work. I was shooting on film and I was not organized. I shot 10 percent of what people shoot today when they shoot digitally so it’s less of a problem than if I was dealing with 10 or 20 times more work. I was terribly disorganized and it’s made everything a lot harder for me. From the moment you start shooting think about an organization protocol. Use key words and dates. At the same time start an organizational file with those key words, dates, and some kind of numbering system. If you can, back it all up on 3 drives. It’s no fun to lose negatives in a flood or a fire, it’s even less fun to have a drive die and lose everything when you could have backed up your work. This is advice I wish I had had. I haven’t lost a lot of work, but I have a lot of work I haven’t even begun to through. Even now, as I scan lots of old work I haven’t set up a protocol for how to name and organize work. It’s idiotic, and it leads to me having to repeatedly repeat work. If you are scanning. Scan at a high quality. If you don’t you’ll end up having to do it all again.

Find mentors; embrace support and feedback

When I got to college I was nervous about taking photography classes. I feared being overly influenced by the expectations of the system. I was also nervous that I would be seen as not talented enough, that I didn’t have a creative enough eye to warrant being in those classes. Instead, I spent several hours a week a a photo book store. There, I had access to so many people’s work that I was able to make sense of what I was interested in. I thought a lot about what those people were doing and what they were trying to do. My decision to not take classes right away was complicated. In some ways it was the right decision because I wasn’t really ready to take them yet. When I finally did take photo classes I had already taken a lot of sociology, anthropology, and philosophy classes. This background shaped the way I began to engage with making images. I thought much more about what they meant than what they looked like. I also started to get some great advice, some of which I’ll detail below. The one thing I didn’t really get from the classes was any understanding of how to engage within the art world. I imagine that I could have if I had tried, but I had a big chip on my shoulder about that system so I wouldn’t have engaged anyway.

Find your collaborators

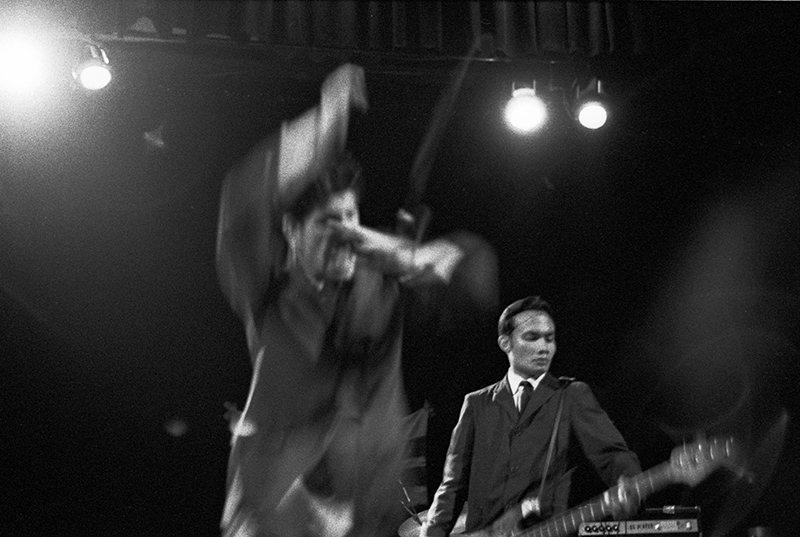

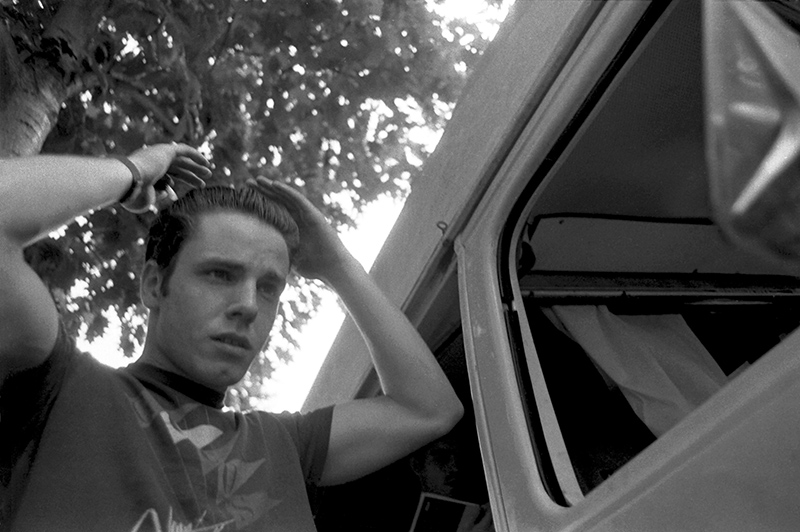

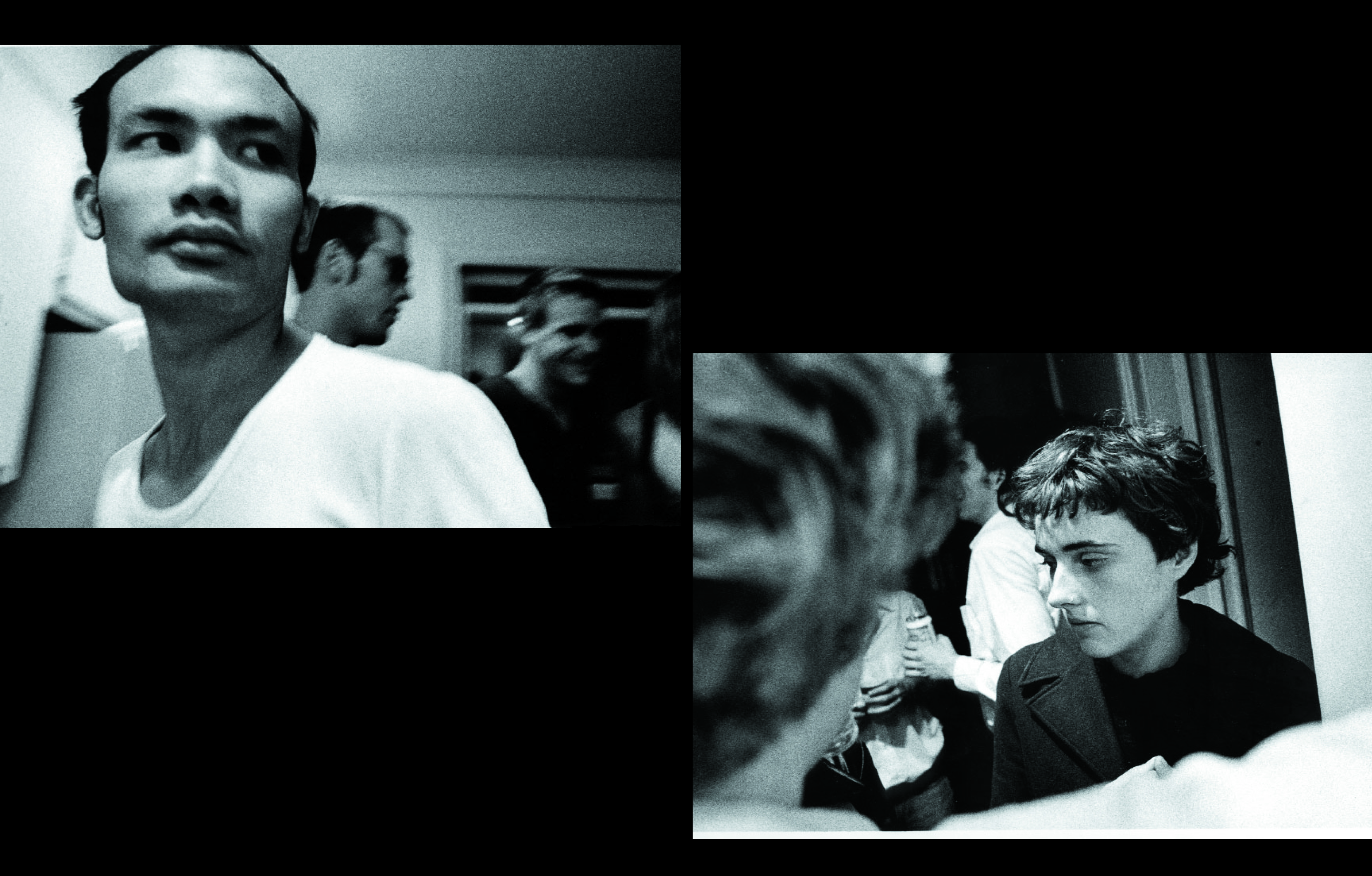

I made a few friends in my photo classes, but I found my community in the music scene. By the time I took my second class I had started a band. Even before starting the band I had begun to take some pictures of bands. Once I was in a band I began to shoot even more, and in a more personal and connected way. The music scene I was a part of was not interested in fame or “success”, and for the most part the bands I shot didn’t achieve any kind of main stream success. This means that I am one of the few people who took photos of them, and that the audience for that work is not a big one. To me though, it gives the work more cultural value because there is a lot less of it. Within this community I found my collaborators and this helped me to find my foundation. All of my 20’s was spent immersed in this community and it gave me a way to make music, images, and films with a sense of purpose.

Start making work

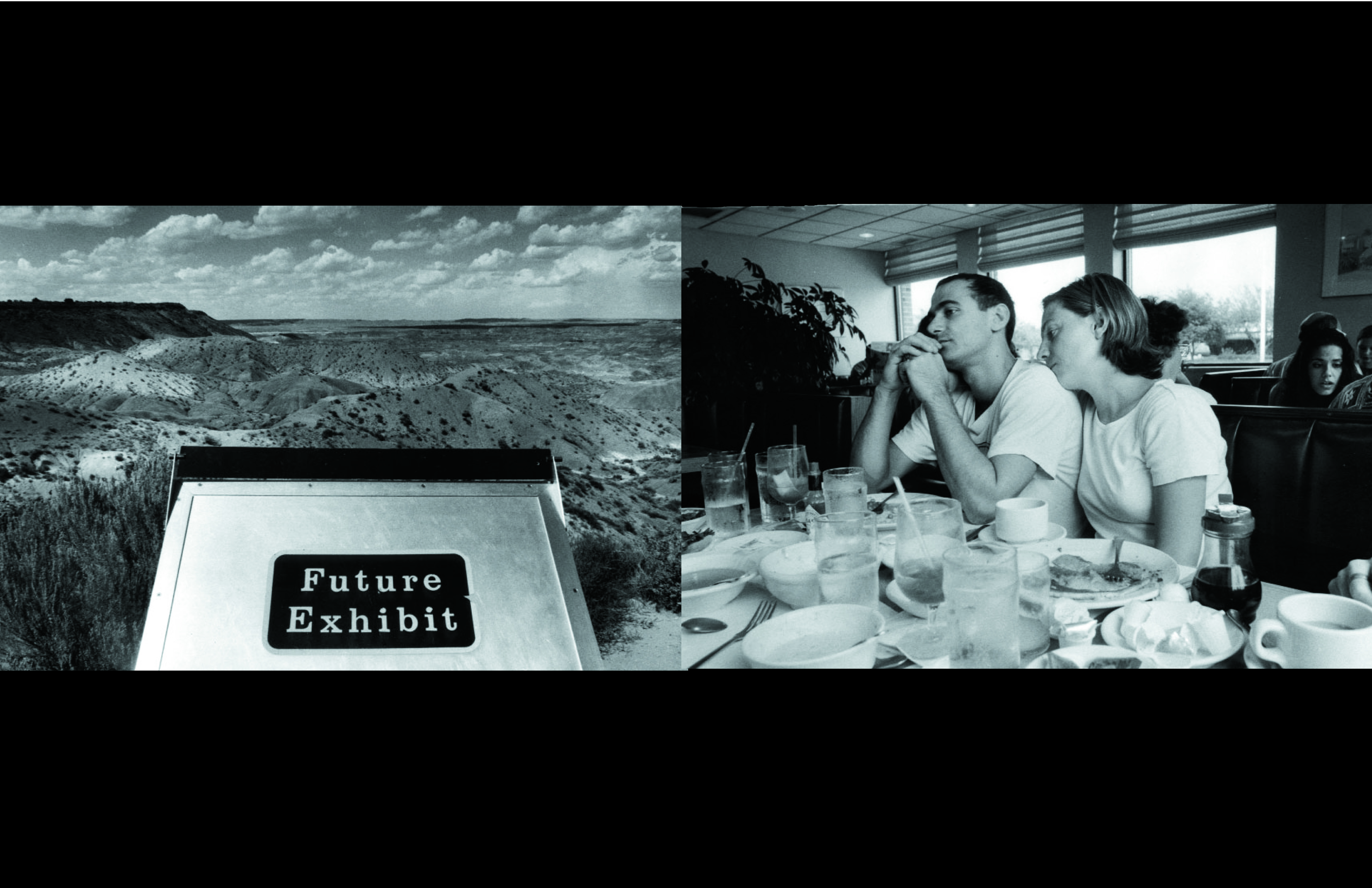

Before I started making work I was practicing. I didn’t know the difference until I did. All of that practice is still work, but it’s largely directionless. I didn’t really begin to make work until I took my first photo class. It was a color printing class, and after we learned the basics we spent the rest of the semester focused on a project. My project was shooting in a mall on Long Island. The teacher appreciated the work and encouraged me to continue it. That summer I drove across the country taking photos in malls. I was definitely not a pro, but the images have a focus and a sense of purpose. As I previously noted, I took a lot of anthropology and sociology classes. For me the mall project was aimed at capturing the mundane details of the mall that would undoubtedly slip away. Unfortunately, that meant that these images didn’t mean much to people at the time. 30 years later they mean a great deal, but that was a long time for a 20 year old to wait. In any case, it was a body of work that had some kind of focus to it.

Learn to look and listen

The next year I took a class in the art school that was a lot more rigorous and focused. After our first assignment we had to show our work to the class. My teacher, Lorie Novak, explained, “As we go around and talk about each other’s work I want you to remember that we don’t want to know what you like or don’t like. That doesn’t matter. Your job in this space it so look at what their work is doing, and what they are trying to do. Sometimes they don’t know yet, and we might see things in it that they don’t. We aren’t here to criticize them, but to help them make more sense of what’s coming across.” [that’s my paraphrasing]

This is the most important piece of advice I ever got. It didn’t just teach me how to give feedback but also how to make use of it. I became a filmmaker and we often do dozens of work in progress screenings of our films for small groups. We learn the most just by observing people as they watch. We look for what engages them; what bores them, and whey the get lost. After the film we can get feedback and we know which feedback is useful largely because it is the feedback that isn’t about their personal likes and dislikes. It helps me to listen better as well. Sometimes it’s hard to not dismiss critique that we don’t want to hear, but it’s always a mistake. We don’t have to do what people tell us, but we need to pay attention to what people are seeing in the work.

When I made street photos in a mall the work was more of a commentary on the commercialization of the public space than the people in that space

Be Thoughtful

As a photographer, I believe it is important that we have the freedom to take pictures in the public space. Street photography wouldn’t exist without this right. At the same time, rights also come with responsibilities. It’s important to be thoughtful about how others might feel about how they are represented in your images. When I drove across the country to shoot in malls I had strong feelings in relation to commercial culture; I didn’t like it. However, when I set out to document in the malls I was very aware of not bringing judgement to my process. I had no interest in making fun of mall culture. In the short term, the work was seen as boring, I think largely because it wasn’t making any kind of “commentary” on the space. When I showed them to people their response was generally, “yeah, that’s people in a mall.” 35 years later the work had a different resonance. This is not to say that we should not make work that makes commentary. I think there is absolutely a need, and a place, for that. However, when we are making work that involves taking pictures of other people it’s best to think about their humanity first. I personally think street photography is wonderful. Still, it can also be problematic when we are blind to some of the deeper implications of our work.

Use what you have

I was in my mid 20’s in 1994 when my future wife and I made a film- on film with no money or support. We set out to take on a close to impossible task. My partner understood how hard it would be, but luckily I didn’t, or I might have not believed we would accomplish it. It was very hard, but from the moment we came up with the idea I could see it happening. 30 years later I understand how important it is to believe in your goals. We got it made but we still struggled to get it seen,

We couldn’t find anyone interested in helping us to distribute it so we threw a projector and our 16mm print in a van and toured it around showing it mostly in rock clubs. That got real boring real quick. When you’re in a band each night offers up the opportunity for creativity, for reacting to the situation you are given. If you show a film it’s like re-living groundhog day; now matter what you do the film is not gonna change. To make our travels more bearable we created an improv band called “drop ceiling” (see bottom for a video of a train ride from NY to NC featuring a live Drop Ceiling performance ) and one of our motto’s was “daring to suck”. Even in an improv band it was too easy to fall back into familiar patterns and tropes, so we had to work hard to try new things, and just as often as not, they did suck. However, when they worked it was often magical. If you ever want to develop your own vision and your own style it can really help if you are willing to sometimes really suck.

Shoot Everything

My next piece of advice would be to shoot everything. It’s a lot easier to wade through images later on then it is to go back in time and capture something that no longer exists. I’ve recently been going back through pictures that I shot 25 years ago and struggling with the fact that in some cases I only shot five or six images of a band. Half the time I got at least one good shot, and sometimes I got none. Whats interesting now though is that the images that didn’t seem so good back then feel wildly important now. I’m also frustrated that I didn’t shoot more mundane images. I think I was trying a little too hard to have every image “say something”. What that “something” is I’m not sure, but with some hindsight I probably would have shot more than I did when I was starting out. Cost and time were certainly a factor, but I also wasn’t sure what it was I was looking for.

Find your focus

At some point you’ll develop a sense of what it is you’re looking for, and you’ll start to shoot less, and with more focus. For now though, shoot a lot and then spend time with your images trying to figure out what works for you and what doesn’t. Don’t be afraid to share them with others but do so without the expectation of praise or affirmation. The key it to listen to feedback without immediately responding to it nor internalizing it. Over the last few years I have been posting a steady stream of images to instagram. I appreciate it when people like certain images. Sometimes it baffles me why they like one image more than others. Even though I have been making images for 30 years I’m still interested in how and what people respond to. This doesn’t mean that I try to shoot images based on what people are looking for, but instead that it helps me to understand what other people are seeing. In some sense all work is about communication and I want to know what’s coming across.

Find respect

Respect what others have to say about your photographs but don’t respect it more than your own feelings and impulses. Look at as many photographs by as many photographers as you can. Think about what you like about them and what you don’t like and go back to the ones that you don’t like to see what you might learn. Just because you don’t understand the work doesn’t mean that there isn’t something there. Don’t be afraid of being derivative of people you like; that’s how you learn. We weren’t born knowing how to talk but learn to speak by hearing other voices. Eventually, if we’re lucky, we find our own voice. I believe that I was too resistant to other influences and that slowed me down. Still these influences worked their way into my process and the mash up of many different voices helped me to find my own. I took three photo classes in college and I got a lot from all of them. Mostly I learned how to listen to criticism without reacting and I learned to listen more carefully when people were talking about the work itself, and what they saw in it, rather than what they liked or didn’t like. Mostly though, I spent several hours a week at a photo book store called “A photographer’s place”. I browsed all the books I could find. This was before the internet existed so the way to experience work was in books, or in galleries. Galleries made me uncomfortable though and I preferred books. Flipping through all of these books made me more appreciative of photographs as part of a whole, that weren’t about a single image, but instead how the work held together- and how the order and the layout of a book was as important to the story as anything else.

Be in the now while knowing that the work will mean more in the future.

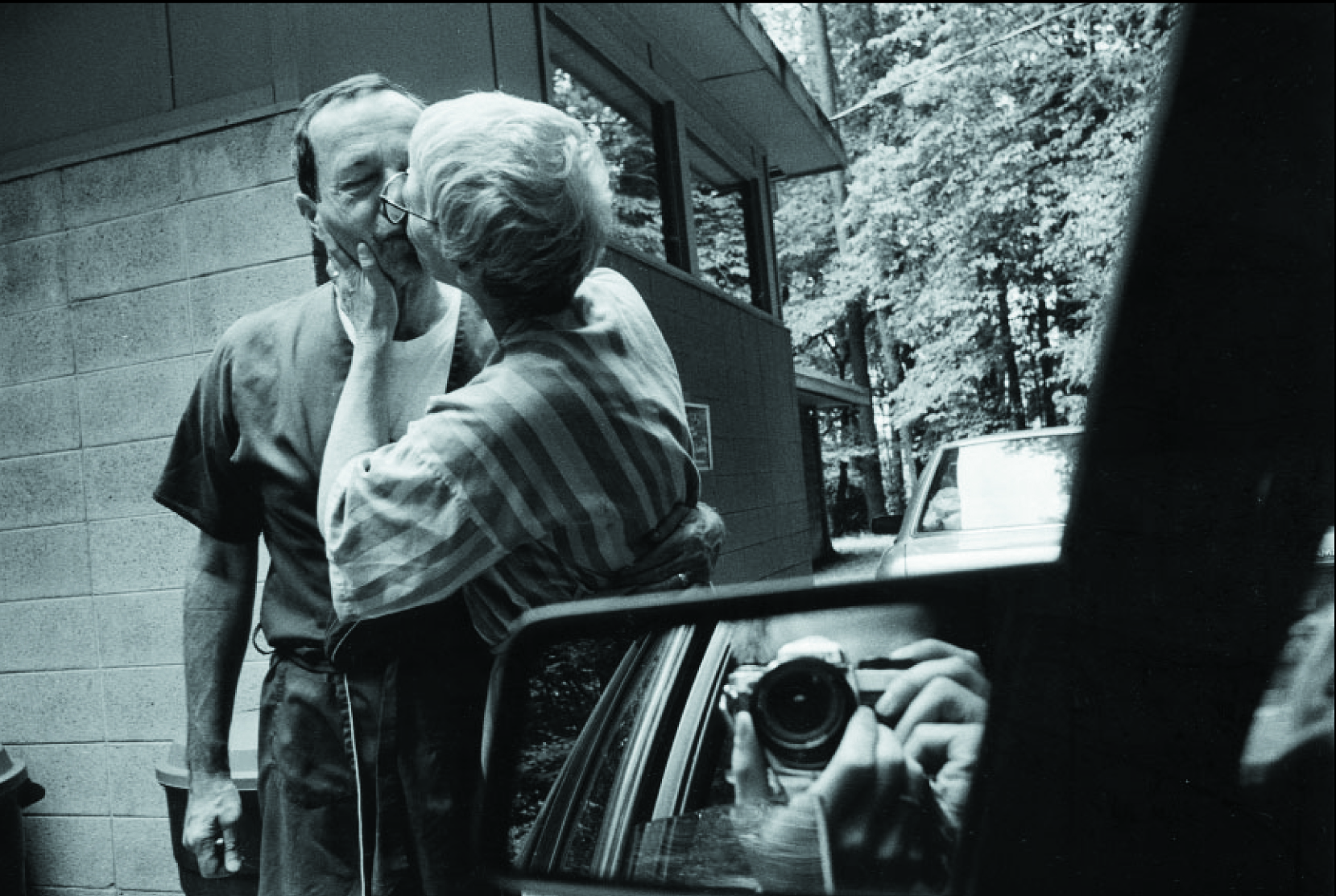

Photographs, like most art, gain more meaning over time. This is why it’s so important to shoot a lot and put much of it away for the future. Think of it as an investment. I’m 46 years old now (52 now) and I started making photographs when I was 15. That’s a little bit over 30 years. What I’ve come to see is that people’s memories of the past kind of reset at around 25 years. At this point the images take on a meaning that no one could’ve predicted. They have a history and emotional impact that is not easy to describe. I think that this effect is even more profound for images that are more observant than they are shaped. When I shot my mall project in 1989 very few people could see any value in it all. I was astoundingly fortunate to have a teacher who encouraged and supported me. If not I probably wouldn’t have driven across the country shooting in malls. Those images have an air of amateurism. I shot with a crappy camera and I was a somewhat shy 20 year old. I went out as a hidden observer and mostly shot from the hip. I was inspired by Gary Winnogrand but I didn’t want to be him. I purposefully shot in color because the mall was so much about color, but also because I didn’t want to be seen as ripping off either him or Robert Frank. I loved William Eggleston too, and the way color made his work. I didn’t want to shoot like Eggleston though. Is the work derivative? It certainly is. However, 25 years later that hardly matters. What does matter is that the work is connecting with people in a very deep way.

Trust that the work will settle into itself

On one level I did trust my vision back in 1989 – but I didn’t trust myself enough to argue that point. At the same time, the work needed time to grow into itself. I don’t think that this means that the work lacks vision, but instead that, that vision needed time to come into focus. I’m finding that the same is true of a lot of the music related work that I did in the 90’s. It’s now about 25 years old and it too is coming into focus. [update- from 2018- the second and third sleepyhead album- and that film half-cocked are getting a second life- drawing room records is releasing those albums with a booklet of photos- and we scanned Half-Cocked in HD and will be getting it out] We can look at it nostalgia, but I think it’s something different than that. 25 years is about the time that it takes for our memories to move from being connected to our present consciousness to a different set of memory banks. When those banks are triggered we are struck by how different things have become. This is not a scientific understanding mind you, just a way of trying to put words to a feeling. These older images feel different and they affect us in a different way emotionally. It’s important to understand this because we aren’t just making images for now, but even more for the future.

Don’t be afraid of the mundane

I shot a lot of things that were mundane, or felt mundane. I rarely printed these at the time as I only had the resources to make one or two prints per roll, but they’ve been aging nicely and it’s been powerful to go through them and find things that work. The most random and mundane images trigger memories that we didn’t even know we had. They spark feelings in ways that more controlled images do not. So as you go forward; trust yourself, be willing to make mistakes, and shoot a lot of things that feel unimportant. It is only later that we can see the value in these moments, but I promise you the value is there.

No Comments