19 May The Long Tale of Distribution

Recently I offered to do a workshop for Sidewalk Film Festival. They asked me to focus on distribution since we have distributed all of our own films. A while ago I wrote a post called “Lessons Learned” about the the lessons we learned from making each film. This post shares some themes, but it is a bit more practical in some ways, and less in others. I wrote it out to give myself a frame for the discussion I will do this evening and I’m sharing it hare.

My partners and I have been making and distributing films for 25 years. During that time the aesthetic, technology, and distribution landscapes have shifted dramatically. Technology advances have led to higher production values with less cost, which has led to a flood of product. This has had a profound impact on revenue streams because, with so much product competing for both eyeballs and dollars, distributors are more choosey and due to SVOD, consumers are less likely to pay for films that aren’t within the SVOD ecosystem. Given these challenges, my advice to young filmmakers has less to do with how to make a career out filmmaking, or how to maximize revenue, but instead how to figure out a way to produce meaningful work and to find a way to get it to the audience that will appreciate it. Sometimes this means finding a way to make work even if there isn’t a budget or an audience to begin with. Over time, with some effort, both can be found… maybe.

We have followed this path, and for most of the time we have had limited access to those systems that provide resources and pathways to audience. So, we have had to hustle and make sacrifices, both economically and artistically, in order to move forward with our work. I personally started out by working as a messenger, busboy, typist, PA, and sperm donor in order to support myself. Later, as we got more work made and developed more skills, my partners and I were able to sell some films. We have also taken on some commercial work in order fund our more personal films. At the same time, we have learned to focus our energy on the projects we are passionate about.

Since most of our work has been produced outside of these support systems, distribution was something that we have had to spend inordinate amounts of time on. From this process we have learned some lessons the hard way. Unfortunately, those lessons aren’t hard and fast rules. This is especially true because as long as we have been making films, the distribution pathways have been in flux.

I have a background in DIY culture that has shaped a lot of my artistic goals as well as the pathways I have taken. My advice has less to do with how to make calling card shorts, or getting an agent, lining up mainstream distribution, or achieving financial success. This is not said as an insult to making a calling card short or finding an agent- It’s just not something I have enough experience to discuss. I also don’t have any easy answers for how filmmakers might adjust to the new realities, but I do have the kind of questions that can help filmmakers clarify their own goals for themselves.

The first question would always be “Why do you need to make THIS project?” Without support you have to have passion to get it done, and if you don’t feel a need to make it, it might be difficult to see it all the way through.

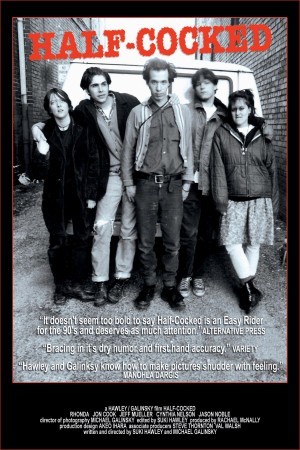

Before I made films, I was in a band and it was that experience which shaped my relationship to filmmaking. At that time, I was also documenting the music world in photos, and our first film, “Half-Cocked”, which was about a bunch of kids who steal a van full of music gear and pretend to be a band in order to stay out on the road, was an extension, and expansion, of that photo work. In order for it to feel right, it had to be “of that world” as much as it was about that world.

One of the first rules of filmmaking is “write what you know”. For our first two films we stayed within that milieu. When we came up with the idea for “Half-Cocked”, it felt like it needed to be made. A few years earlier, right when I had started a band, a friend of mine who worked for the head of MTV told me “Alternative is going to be the next big thing. It’s been decided.” I found this to be shocking and alienating. It made me angry. By the time we chose to make our film I saw that it had come true, and that this commercial reality was starting to have a major impact on the world I was a part of. Staunchly independent bands were signing major label contracts and the cohesion of the music scene was suffering for it. The bands that might have sold 20,000 records on a small label, which helped that label put out 5 or 10 other albums, were signing to the majors which disrupted that entire ecosystem. It felt like we had to document it before it was gone, and that sense of urgency helped push us forward.

If you are conceptualizing a film you want to make, there’s a lot of value in trying to figure out what kind of stories, actors, characters (if it’s a documentary), and locations you have access to. While it’s nice to dream big, It’s a good idea to think about figuring out how to make a film that is possible for you to make. This is especially true at the start, because we learn the most by doing. My daughter is 18 and plans to study film in college. I have been practically begging her to make things, anything. The more you fail, the more you learn. With inexpensive cameras and no film cost, there are unlimited possibilities in terms of how many times we can fail. This process becomes something of a practice, like practicing the guitar or engaging in meditation. We learn what these things are by doing them over and over, occasionally with feedback or instruction- though those aren’t absolutely necessary for learning to occur. The best teachers help us hone in on what we are already doing and helping us to do it better. The worst teachers tell us we are doing it wrong.

I did not take any film classes in college but I had a few photo ones. In my first class in the art school my teacher gave me the most important advice I ever got and it still is foundational to my filmmaking practice. She told us that during a critique of each other’s work we should not tell the other artists what we liked or didn’t like about their work, but instead focus on what we saw in it, what we were getting from it, and help them to understand what was coming through and how they might focus their effort. This not only helped me to be a better ally, it also helped me to differentiate between useful and less useful critiques. As we do our rough cut screenings it helps us hear what’s being communicated, and what’s confusing people. Rather than respond to their exact notes we are able to figure out how to adjust our work so it accomplishes what we want it to.

It’s also a good idea to think about who the audience for those films are. You don’t have to limit it to that audience, but having some sense of it can help shape your aesthetic and your process. Sometimes we start to find our audience and our peers by putting our work into the world. One of the early lessons we learned was to “dare to suck”. If you are afraid of failing you will play it safe. If you play it safe you won’t challenge yourself artistically or emotionally. It’s these challenges that push us to grow. However, if we do this, we also have to be able to recognize the failures as failures and learn from them. Sometimes these “failures” aren’t really failures as much as failures to live up to our goals and expectations. They also may just be failures in the sense that we fail to find and connect with our audience. If our audience is very targeted its a little easier to reach it, but even then it can be difficult.

When Suki and I were making Half-Cocked, we were vaguely thinking about distribution, but we didn’t really know what that would look like except that we hoped to take it to film festivals where we might find someone to distribute it for us. At that time, the route was pretty clear; Film Festivals led to possible indie distribution via independent theaters. Then maybe it would end up on cable and DVD. We knew that it wasn’t a “Hollywood movie” we were making, but we both grew up seeing a lot of films in our local art house theaters. Further, the success of Richard Linklater’s “Slacker” made it seem even more possible that our film might find an audience via this route.

When we were making the film the internet was still not a major part of our communication or entertainment lives. It was growing, but we didn’t even have email until we had a script, and our email was the name of the film (halfcook@aol.com). I think AOL censored the name halfcocked – and my partner Suki and I shared the account. I guess that was lifetimes ago. The point is, we had to do everything in ways that was wildly more difficult than it is today. We shot on film, so we couldn’t shoot so much of it. We edited on film, so we had to keep track of every little piece of both the sound and the picture during editing. It made the editing much slower and much more specific. All of the shooting required lights (and an understanding of how light worked), processing, and money. We relied a lot on the book “Feature Film Making at Used Car Prices”. My partner Suki was in graduate film school, and she had gotten an undergrad degree in film, so she pretty much knew the ropes, but there were a lot more moving parts back then, and so many things that could go wrong. It took all of our energy to keep it moving forward, which left us no room to think about what we’d do with it.

We also had some kind of Sundance distribution handout that had a list of festivals. None of this stuff was online, so we had to rely on experts and connections. We didn’t have a lot of those, so the first year after finishing the film was tough. The truth is, my partner Suki had worked in the office at Sundance in LA and at the summer sessions in Utah. She didn’t feel comfortable reaching out to her old boss. That was probably the biggest mistake we made. Had the film played there it might have gotten seen within the film eco-system which would have helped us a great deal. It’s one thing to try to force connections with people, and its another thing entirely to not reach out to the people that you know. So always be respectful of other people, but also reach out to those people that you know.

My first piece of really solid advice is to think about how you might get your film seen by your target audience- and if possible begin engaging with the audience- even before you’ve shot a frame of film. Belief is a powerful drug. I didn’t have the knowledge of just how hard it would be to make the film, so I believed it was possible. I was the optimist. Once we decided we were making a film, before we had even 3 pages written, I began to tell people about it. This was brilliant and/or incredibly stupid. However, the belief that I had, and the pressure I added helped to get it done. After talking about it as much as I did we kind of had to make it.

By creating the understanding that it would exist we built up a sense of expectation and awareness. This also gave us a reason to reach out to bands who might give us a song for a soundtrack. While we didn’t reach out to Suki’s Sundance contacts we did reach out to a record label that we knew, Matador Records, and they gave us a small advance for the soundtrack which, though small, paid for all of our film and processing. For years I had taken pictures of bands for free, so, many were happy to give us a song to help us get the film made. In the end, that label also took a chance and released the VHS as well as the soundtrack and that’s how most people ended up seeing it. Before the internet movies could slowly go viral via VHS. It happened with “Heavy Metal Parking Lot”. While our film didn’t exactly go viral, it’s kind of amazing how many people saw the few thousand VHS tapes that were produced.

THE FIRST SHOOT

We were young, had to rely on a lot of people, and had no money. It was a very hard shoot, way harder than I could have imagined. Given all the obstacles we faced in making it, the film was surprisingly good. However, while there was a clear audience for the film in the music world, we had trouble enacting our distribution plan which relied on film festivals to get people to know about it. Despite getting a wildly positive review in Variety from our cast and crew screening, we spent a full year submitting it to film festivals and got rejected by 35 of them before we gave up and set up a month of weekend screenings in an art gallery on Ludlow Street in NY.

That was an amazing experience and it prompted us to start showing it in rock clubs. If Lesson 1) was “make what you know”, Lesson 2) is, “if you hit obstacles within the film system, bring it to the audience directly”. Lesson 3) might have been – “make connections, because without them you’re lost”. We didn’t have strong film connections but we did have a lot of music scene ones. For us, going directly to the audience meant showing our rock and roll-themed film in rock clubs. We had to do it via a 16 mm projector plugged into the soundboard. Thankfully, the clubs were willing to show it and we had the energy to go and do it.

Now there are a lot of other ways to do that kind of distribution- there are even whole online systems to crowd source the audience –Gathr (which we have used). However, you will still face the same problem that we did at the time; asses in the seats doesn’t necessarily translate into dollars in the pocket- especially if you have to be present at the screenings to make it happen like we did. With Gathr we were able to get the films seen in more places but the work to revenue ration is pretty damn low. We got the film to the audience, but we didn’t understand enough about building and maintaining an audience in a way that would help to sustain us. This is something that we are still working to understand 25 year later. Lesson 4) “engage and connect”. If we had done a better job of that from the get go we might have had a lot more success reaching our audience with subsequent films.

To be fair to us, pre-internet this was wildly hard to maintain because it would have meant bi monthly postal mailings. Over time we have built up a fairly robust website and Facebook pages for each film, but we haven’t been able to build the kind of audience that would make it possible for us to keep cranking things out.- and this is partly because the way we work doesn’t lend itself to “branding” and in fact we hate the idea of “branding”, but in the end branding is the way that people connect with an audience.

To Recap-

1) Make what you know

2) If you hit obstacles with industry go directly to your audience

3) make connections within the system (this actually might be rule number 2)

4) engage and connect.

All of those probably seem very obvious, but they weren’t to me when we started out.

Again, our efforts to go direct to the audience went really well. However, they didn’t bring in any real revenue. From a financial perspective, “Half-Cocked” wasn’t a great loss because we spent very little money to make it. However, it took a lot of labor from a lot of people to get it done. Creatively, there were a lot of lessons learned, and there was much about it that was deeply rewarding. Still, it was frustrating that while we got it in front of the audience that wanted to see it, it never really made it into the realm of the film world.

We made a music-themed follow up to “Half-Cocked” called “Radiation”, shooting it in Spain about three years after finishing “Half-Cocked”. This film had a lot more success on the festival circuit. Once again, we used not only what we knew, but also who we knew, to get it made. The main character was a guy who put out records for my band in Spain and set up tours for us. So we set up a tour for “Half-Cocked” and we used the locations to film in. We wrote a script based around what we had to work with. We shot it on 16mm but edited on video and blew it up to 35mm for its festival run. We got some great excitement from the distributor Palm Pictures after it screened at Sundance, NYUFF, and SXSW. They were going to distribute it if an important theater, Film Forum, showed it. Despite the fact that Suki had worked there selling popcorn, they weren’t interested, and the distributor passed. We probably could have lobbied them to show it, but once again we didn’t use the connections we had to make it happen.

Frankly, after that, no one outside of the festival circuit saw the film. This was pretty crushing. While the same audience existed for this film, it was on 35mm, which meant we couldn’t project it on film in rock clubs, and digital projection wasn’t yet good enough to take it out that way. While we had some good festival support, we didn’t have the resources to push it into regular theaters. If I had to do it again, I’m not sure what I would do. I might have found a way to get it on screen ourselves but we were burnt out and broke. Like our first film, it didn’t cost what a comparable film might have cost because we did it with such a small crew. Still the full budget was over 100k, which was a lot more 20 years ago, and we were never able to pay anyone back. That bothered us a lot. We had also hoped that the film would help us, and others, with their careers. It did do that for a few people, but we were still at the edges of the film world and weren’t sure how to push forward with another film without support. We were a little demoralized by the experience and we still had no real understanding of how to work within the film world.

DIGITAL

That’s when Digital video cameras started to become available and we pivoted to documentary because we could do everything ourselves. The technology was perfect for those films but not exactly up to snuff for narrative work just yet. We kind of fell into that world, but we weren’t really of that world. We had no “background” in documentary so we were starting over from scratch in many ways in terms of connections. At the time I was working at a music website and Suki was doing some editing for other people. We were also trying to get other projects off the ground. Having our own camera opened up a world of possibilities though. Over the next 15 years we made a half dozen documentaries- for the most part without any budget in advance. This gave us a lot of artistic freedom, but it also made it increasingly hard to sell the films because companies pivoted towards documentaries that were produced in house rather than acquired.

The first doc we made was about an underground publisher who was re-publishing a discredited bio of GW Bush. It was a long up and down process as we struggled to follow the story and keep it moving forward with no outside resources. To be clear, we applied for dozens of grants, but our work didn’t fit the expectations of most of them.Our last day of shooting was sept 9, 2011. The film was almost done and this final scene followed our main character as he moved out of the basement of the building he was the superintendent of. He had squatted the basement for his publishing company. Two days later the twin towers fell and no one wanted to say anything critical about Bush for almost a year. So we were in kind of a limbo. Eventually we got the film into the Toronto Film Festival and that helped us launch distribution of it ourselves, and we got it short listed for the Oscar. That helped us sell it to several TV channels including HBO and we actually grossed about 250K which was a great deal of money for us.

This helped us to get our next film started. “Code 33” was a doc about the search for a serial rapist. Once again we had to get the thing made before we could do anything with it… kind of. We got editing money from HBO after we shot the whole thing. We then showed them a rough cut and they passed on it without any notes. That was it. We went on to finish it but they were really the only channel that might have acquired it- and despite incredible reviews in Variety and Hollywood Reporter they wouldn’t consider it again. We showed it to all the distributors but no one knew what to do with it. Later the cops became stars on an A&E show called The First 48, so they gave us a big chance of money to shoot the trial as well and recut our film into television. That floated us for a while and it helped us to hold onto the idea that persistence matters. It would have been very easy to give up, but luckily it worked out.

At this point my filmmaking partner and I were nearing 40 and felt a need to get a little more stability. We were working on several unfunded films and with our partner David we were pitching a lot of ideas but found it very difficult to get funding in advance. Over about a 5-8 year period we applied for upwards of 100 grants and didn’t get any of them. Once again our greatest asset was our persistence. While we started a few projects we weren’t able to finish, we finished several projects that took nearly ten years to finish, and we have others that we have worked on for even longer.

A few years later, as we worked to finish our next film “Battle for Brooklyn” we turned to the upstart crowdfunding site Kickstarter about three months after it launched. We ran a successful campaign to raise 25K to get us over the finish line. While it wasn’t a huge sum in terms of what films actually cost the process of raising the money connected us to our audience directly and made them partners when it came time to release the film. This was a film about a community fighting a massive land grab. We got a lot of big fest rejections. However, once we got into Hot Docs we decided on our release plan which involved distributing it to theaters ourselves. We planned to show it at two festivals we had good relationships with- Brooklyn Film Festival and Rooftop Films within a week of each other and then launch it in theaters the next week. The plan worked out perfectly. It was opening night at the Brooklyn FF and then played at Rooftop. It got huge press support and did really well at the Theater. I did q and a at every screening and ran myself into the ground. Unfortunately it was hard for us to get other theaters to run it after that as it was seen as a “local” story. Still, like “Horns and Halos”- and another film we distributed for friends, “Occupation: Dreamland”, we got it Short-listed for the Oscar.

Here’s where the shift in distribution patterns hit us hard. Despite the critical support, the box office success, and the Oscar short listing, we had no offers to put it on TV. We were able to sell about 100 copies at educational rates and eventually sold it to Direct TV for 30k. However, we spent 10 years on the film and didn’t come close to making back our hard costs. In many ways the film got seen, but the revenue wasn’t there at all. However, we made the film because we were concerned about what was happening. The developer that was going to benefit from the taking of the land spent millions on publicity and that shaped the public understanding of the narrative. Our film changed that narrative, and it helped dozens of other communities gain insight into what was going on. So on that level it was a major success. It also paved the way for us to get our first grant, a Guggenheim, and that was an important boost.

We pivoted with our next film. We finally got some production budget for a film about a mother searching for her missing son for 30 years. MSNBC agreed to pay of an hour long TV piece but wouldn’t give us a budget for a full feature film. However, the agreed to let us release our own film after they aired their hour long film. The budget allowed us to shoot the whole thing. We turned in our cut of “Missing Johnny” and it was supposed to air on a Sunday. However that week there was a mass school shooting in Connecticut and it was pulled. They aired it later but I don’t think anyone saw it. It took us another year to make our film, “Who Took Johnny”. We premiered it at Slamdance and played it at a few other festivals but couldn’t drum up real interest. A year later Sidewalk asked to show it and the led to an offer from a sales rep who got it on Amazon and iTunes and sold it to Netflix – where it totally took off. However, the audience wasn’t really a film world one, and since it wasn’t a festival hit it almost didn’t exist in that world. Once again we used Kickstarter to help us finish it and that also helped us to promote it.

We did the same thing with our next film “All The Rage”. This film, about a doctor who believes that back pain is a mind body problems should have had a lot going for it; the doctor sold millions of books and had countless famous fans, many of whom are in the film. However, his ideas are so emotionally and intellectually challenging to people that it was almost impossible to get anything written about it. Once again, we turned to Kickstarter to get it done. We raised a good amount of money to finish it and help cover some of our publicity costs. We hired 4 of the best publicists in documentary- and couldn’t get anything beyond a mostly dismissive reviews written. For the past three years I have worked on the distribution almost every day. We put it in theaters and got it qualified for the Oscar. It was the first film we failed to get short listed that we distributed. After about a year we put it up on Vimeo on demand first because we had the most control over that, it could be in every country, and we got more of the revenue. Over the past 3 years we have made over 60k on that platform. We also used Gathr to get it in theaters. We then got it up on Amazon and iTunes using Bitmax. We have made major efforts to connect with the health care and wellness communities, and the audience for the film continues to grow. Like “Battle for Brooklyn” it also had a massive impact on people. Hundreds of people have let us know that the film saved their lives. So, in that sense, it is by far the most important film we’ve made.

In the end, if we focus on work that has meaning to us, it will have meaning for others. Success isn’t always best measured in terms of money earned, or eyeballs reached. Instead, real and lasting value comes from connecting with others in way that give their lives more meaning.

No Comments