15 Jul A Glut of Goodness Does Not Look Good.

My partners and I have been making, and distributing our own films for 20 years, so people often come to us for advice about how to get their films seen. Unfortunately, I’m not the best person to ask because we don’t always make the best decisions. Like all artists we struggle with getting our work past gatekeepers like festival programmers, distributors, theater owners, and press people. Sometimes we get our work past one, only to run straight into one of the others. Some people think the internet and digital distribution will bring democracy to the process. Unfortunately, the flip side of increased access to the means of production means a glut of product. Increased avenues of distribution means a fractured marketplace, which, when coupled with a glut of product, doesn’t look too good for filmmakers.

Having been through the “increased access to the tools of production” and “increased access to audience” roller coaster as a musician before I was a filmmaker, it’s clear to me that this story is repeating itself. There will be some big winners, and a beach full of people struggling mightily to be heard.

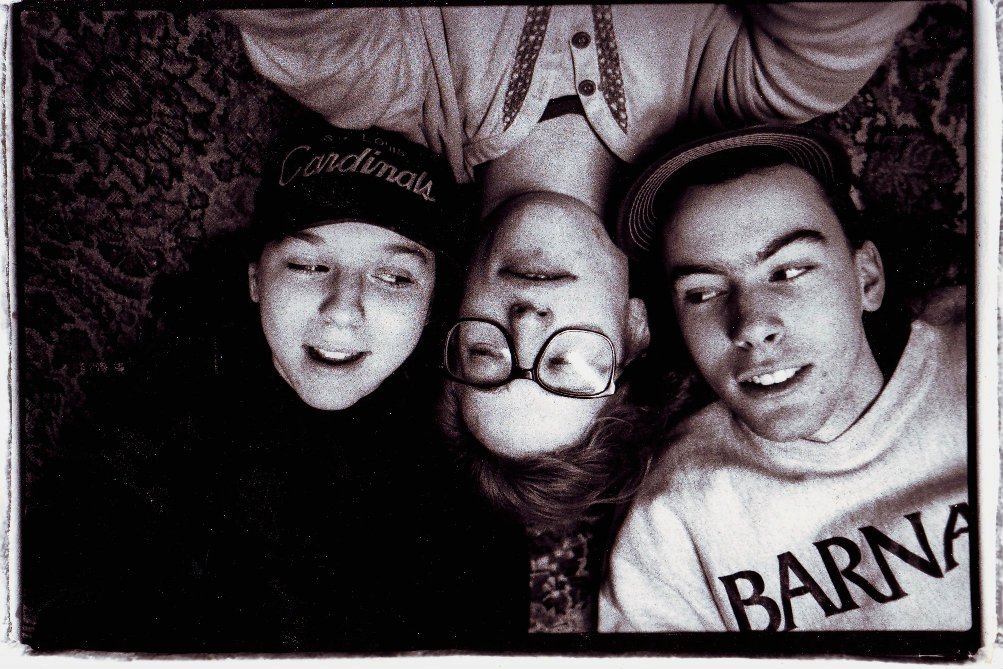

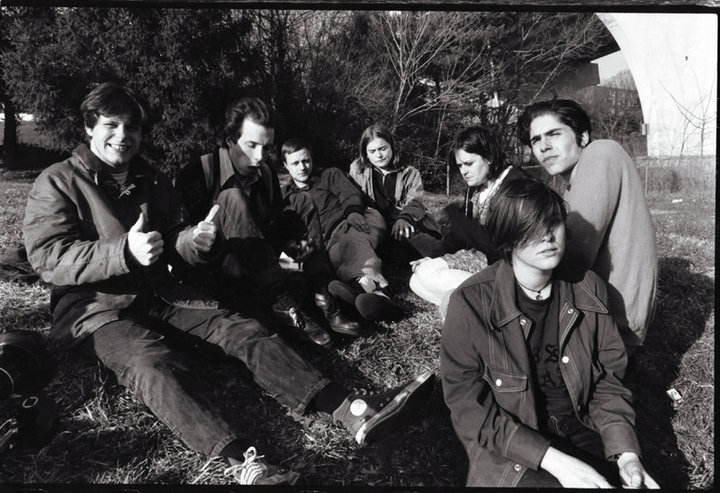

I started a band with some college friends in 1989. By the end of that school year we had made up a few songs and recorded them. This was before the internet was a real part of our lives, and digital sharing of music was still about a decade away. In the late 80’s and early 90’s 4 track machines and other lower cost recording technologies combined with a do it yourself aesthetic to spark a groundswell of 7’ single production. I was a record collector at the time, and at first the flow of new singles was slow and steady. It was an exciting time because interesting new music was bubbling up from Seattle, to Louisville, to Chapel Hill.

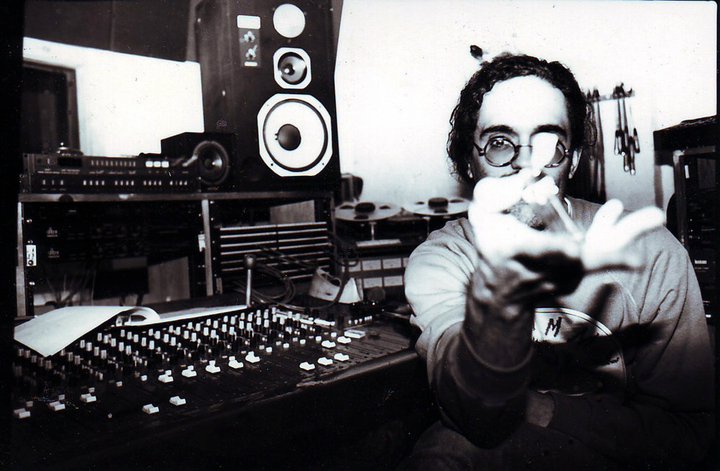

After 8 months of practicing we wanted to record a demo and ended up recording with a musical hero of ours as he ran the cheapest, fastest studio around. We were a bit of a mess but the recording came out sounding pretty good. We met a drummer that summer who liked our band and he had a small label. He put out our first single and got decent airplay on college radio. Lower recording costs and low cost 7” inch pressing made it possible for almost anyone to make a record. At first it was exciting, and then it quickly became unbearable. Each year the number of “indie rock” bands putting out music seemed to increase exponentially. It got so bad that our friend Tim put out a single with his band Two Dollar Guitar called, “Everybody’s in a Band”.

Digital production and distribution made the torrent of music a tsunami. After four albums, a half dozen singles and EPs, and a decade of touring, I left the band in 1999 to concentrate on filmmaking. I left at the tail end of the recording of our last record. It came out, but it didn’t really make a dent in the world. I think it was by far our strongest album.

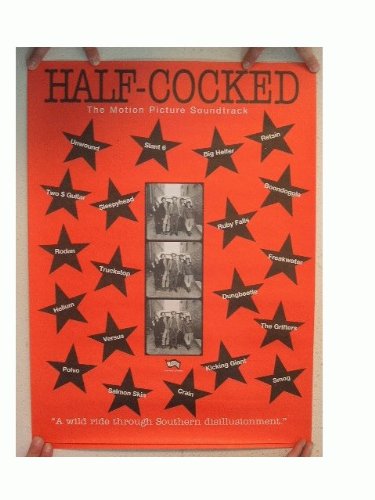

I had started making films while I was in a band. In 1994, before video became a viable way to make films we shot our first feature on 16mm. Even though there were a lot fewer films then, we still had trouble getting our films past the gatekeepers. As such we have had to be both creative and tenacious. When we finished our first film, “Half-Cocked,” a black and white ode to underground music in the early 90’s, we were surprised by an amazing review in Variety. A friend had brought a writer to our cast and crew screening. We got a call from every Hollywood studio, but unsurprisingly, none called back after they’d viewed our glacially paced art film. However, it was a bit surprising when over the next 6 months, the film was rejected from at least 30 film festivals. Finally, nearly a year after we finished it the Athens (Ohio) film festival agreed to show it, and a few months later it played a couple of newly formed underground film festivals in New York and Chicago.

However, we hadn’t waited around. Instead we took it on the road showing it mostly in rock clubs, bringing it directly to its audience. We eventually put out the VHS on the same record label that put out the soundtrack.

Our next film, “Radiation” found some success on the festival circuit, showing at Sundance, SXSW, and over 40 other international fests, but it never got any kind of distribution. That same year, 1999, we seized the means of production; acquiring a video camera, and we started making documentaries. Our first effort, “Horns and Halos” had a bumpy festival ride but was eventually short listed for the Oscar after we put it in theaters ourselves. It was picked up by HBO as well as several other international TV stations. At the time, TV paid fairly well, and we were able to scrape by for a couple of years while we worked on our next film, “Code 33”, where we followed Miami cops for an entire summer as they searched for a notorious serial rapist. Again, we struggled to get it made. We got into some good festivals and got amazing reviews but we couldn’t sell it. Eventually our cops became famous on a TV show, our rapist escaped, and after he was re-captured we shot the trial. We chopped our movie and added the new footage and sold it as a two hour TV special. It was nice to get paid but depressing to tear apart the film we were so proud of.

We had already started several other projects when we made Code 33, and we finished one of those, “Battle for Brooklyn” in early 2011. During the 10 year period from 2001-2011 we had applied for at least 2 dozen grants but we never got any. Kickstarter came along as we struggled to get it done, and we became one of the first projects to raise over $25,000 on this new platform. While we didn’t get any of the grants we applied for, we did get some support from one wealthy donor via a group called the Moving Picture Institute. When we were very broke my brother also stepped in to help out.

In order to make sure that the film connected with people we did over 25 small group screenings as we honed the cut. We knew it was done when no one checked their phone during the screening. After getting rejected from a number of important US festivals, we were invited to the most important North American documentary festival, Hot Docs. At the festival the response was ecstatic. Our first screening erupted in a standing ovation. Out of over 200 films in the festival our film was the 16th most popular with audiences. Usually when you play your film at a festival like Hot Docs, other festivals want to show it. For some reason no one else would. Still we were able to arrange to screen it at the Brooklyn Festival as the opening night film, which meant it got a lot of press and attention. We then opened it theatrically the following week, and we did amazingly well at the box office. Then to our great surprise, no other theater would book the film, thinking that it only did well in New York because it was a local story.

The herculean effort that it took to do this on our own crushed me. By the time we opened the film in New York, I was so stressed out that my left leg was seized up in a constant cramp. I could barely walk from the car to the theater where I introduced and did Q and A for every screening that opening weekend. I was so burnt out and frustrated when no one else would show it that I ended up collapsing in pain on my office floor, and remained stuck there for almost two weeks. I had a lot of time to reflect, and I vowed to do things differently moving forward. We also began to work in earnest on our film about the work of Dr. John Sarno. Eventually, as the Occupy movement took off, interest in our film grew as the film dealt with similar themes. In the end our efforts paid off and Battle became our second film to be short listed for the Oscar.

In the meantime, we got some funding to move forward on another documentary about Noreen Gosch’s efforts to obtain justice for her son Johnny, who had been snatched off the street in 1982 while delivering newspapers in Iowa. The local police still consider him a missing person, rather than a victim of a kidnapping despite reams of evidence to the contrary. We got the funding for a short TV version but retained the rights to make a feature. We then spent another year crafting a narrative that we are exceptionally proud of.

Unfortunately, we once again clanged against the gates. After being rejected from a few major film festivals we decided to go ahead and premiere the film at Slamdance (out of competion) because we feared repeating the same process that we faced with “Battle for Brooklyn”. We believed that with our track record of making strong docs, that we could get people to pay attention at Slamdance. We were wrong. Once again, no major festivals would take our film, and despite playing at nearly a dozen smaller festivals, winning special jury awards at both Newport Beach and Chicago Underground, and the audience award at the Brooklyn Film Festival, we have gotten only a couple of blog reviews of the film (all ecstatic), and a very nice quote from John Waters – “An amazing, lunatic documentary that will leave you creeped-out, excited and surprised.” When I googled the film just now a rotten tomatoes link came up. They have no reviews and can’t seem to find any images for the film. In many ways, our film barely exists. However, having been at many screenings of the film, I know that it has a powerful effect on people. The disconnect between the quality of the film, the audience response, and our ability to get it seen, can be incredibly frustrating.

While we are great storytellers, we haven’t always done the best job telling our own story. We make films about people with problems, and that, in itself, is problematic. Gatekeepers want clarity; they want a white hat and a black hat. We make films about the person in the gray hat.

I do what I can to help people navigate the constantly changing world of production and distribution. My best advice though is to trust your gut. Your gut never lies.

No Comments