27 May New York Storied

I recently re-subscribed to the New Yorker. I hadn’t renewed a few years ago because I had gotten overwhelmed by issues piling up on the back of the toilet. However, I came to miss the writing and the connection to what’s “happening,” culturally-speaking. When the 25 dollar subscription offer came for the 10th time, I decided I couldn’t refuse. I’m glad it is coming again. I love the cover of the last issue (Comey dragged from a plane by Sessions), and found myself laughing out loud to the fiction piece “A Love Story.” This article on Gerhard Steidl by Rebecca Mead was really interesting to me as well. It was also a bit difficult for me to read. I had a very different experience than my friend Ken Schles did in regards to having a book published by Steidl. This is because while Steidl printed my book “Malls Across America“, it came out on a Steidl imprint called Miles/Steidl and I never had any contact with the man himself.

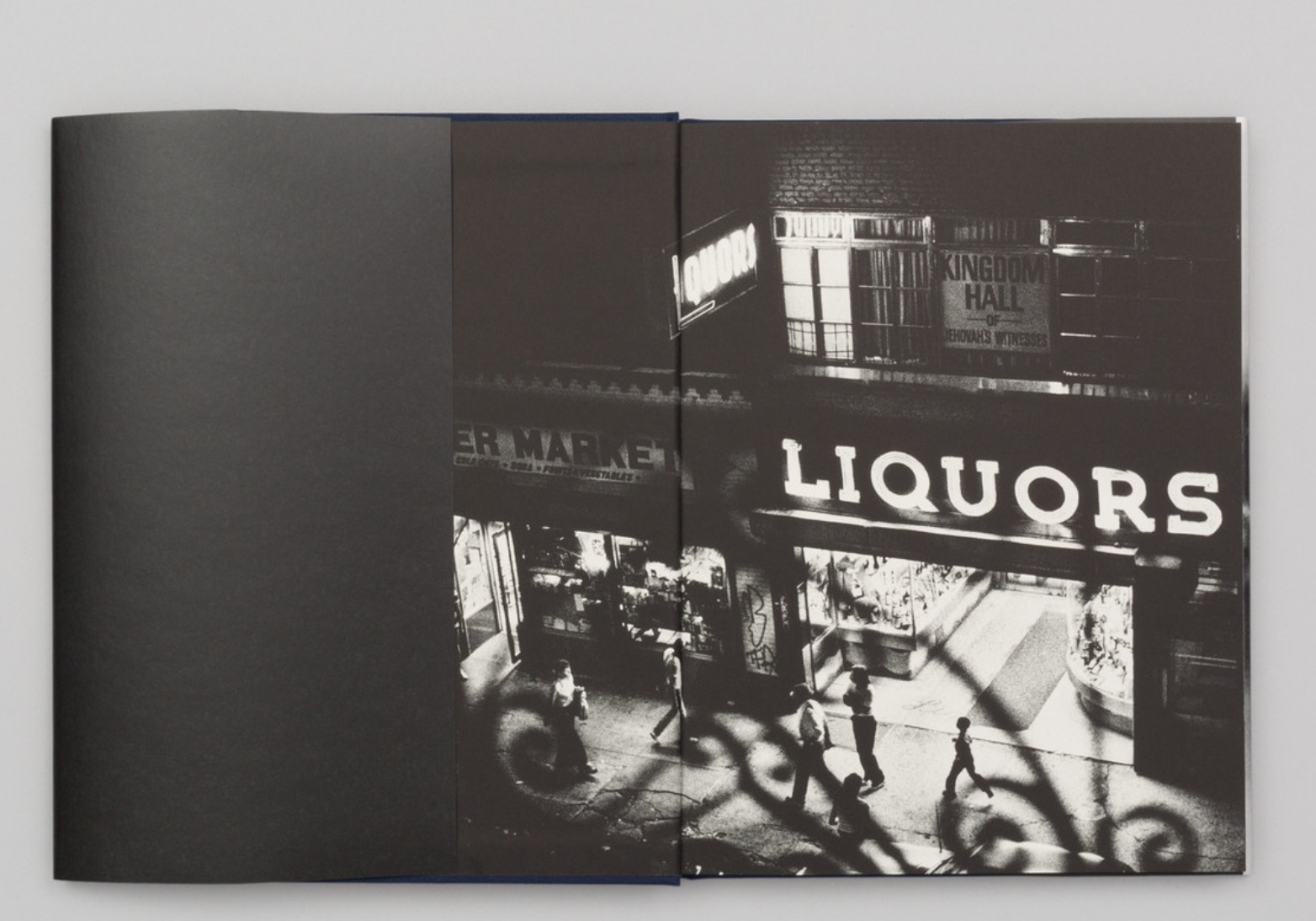

-Inside front cover of Ken Schles’ “Invisible City” recently re-printed by Steidl- image from Steidl website

The world is exceedingly small. When I was putting my mall book together, my kids went to the same school as Rebecca Mead’s son, the the author of the above-mentioned article about Steidl. I mention Ken Schles’ book because he is a friend (and this started out as post on Facebook in which I was tagging him). When I bought a copy of Ken’s book “Invisible City” on the street in 1989, I did not yet know him and in fact never really paid attention to his name because I was completely drawn into the mysterious images in his book. The book made me think a great deal about image-making and how images could build on each other to create a greater whole. It had a profound impact on me as an artist. In fact, I formed such a romantic view of the East Village from his work that I inadvertently ended up moving into an apartment in the same building as Ken that looked out upon the view in the photo above (my view was one floor below the above image). I didn’t realize it was the same view – or that it was the same building – until 6 months later when a friend asked me if I knew Ken. She thought I would like his photos since they were so much like my own. When she said that, I searched for my copy of “the book,” but it took me a couple of weeks to locate it in a box at my previous apartment. Looking through it was shocking because a number of the pictures were taken in my building.

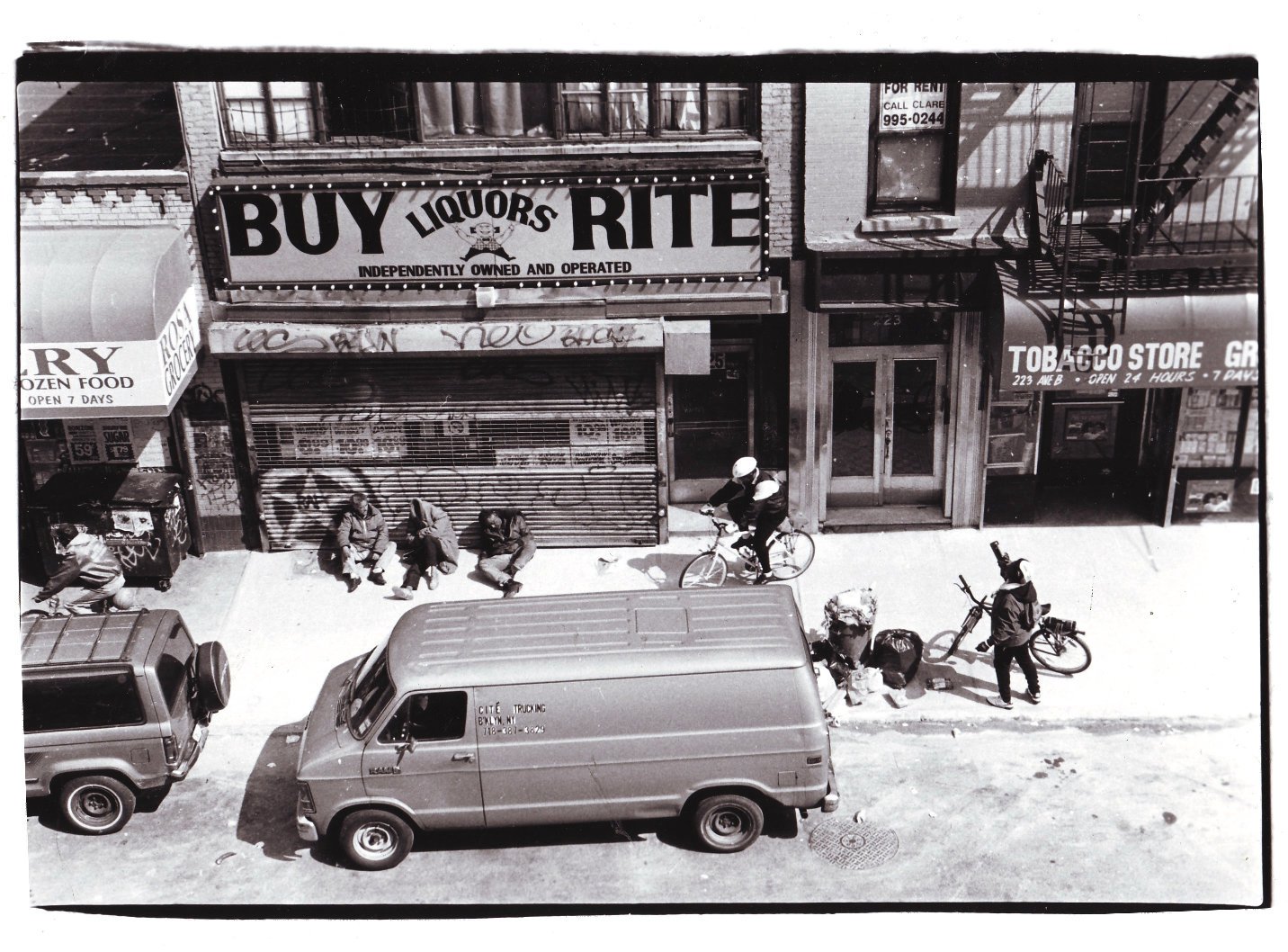

-This is a photo I shot from my own window before I realized that my apartment was related to Ken’s book

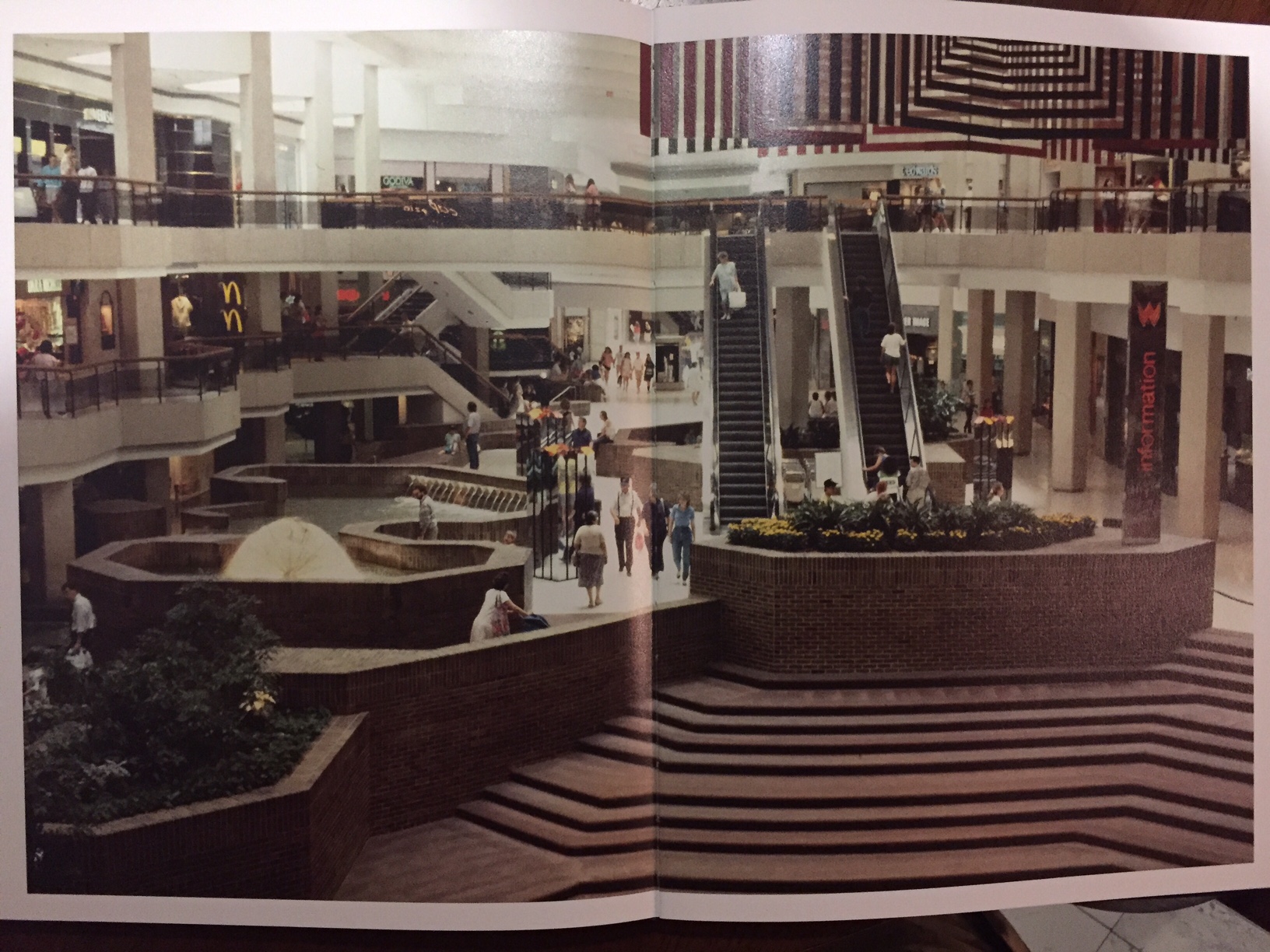

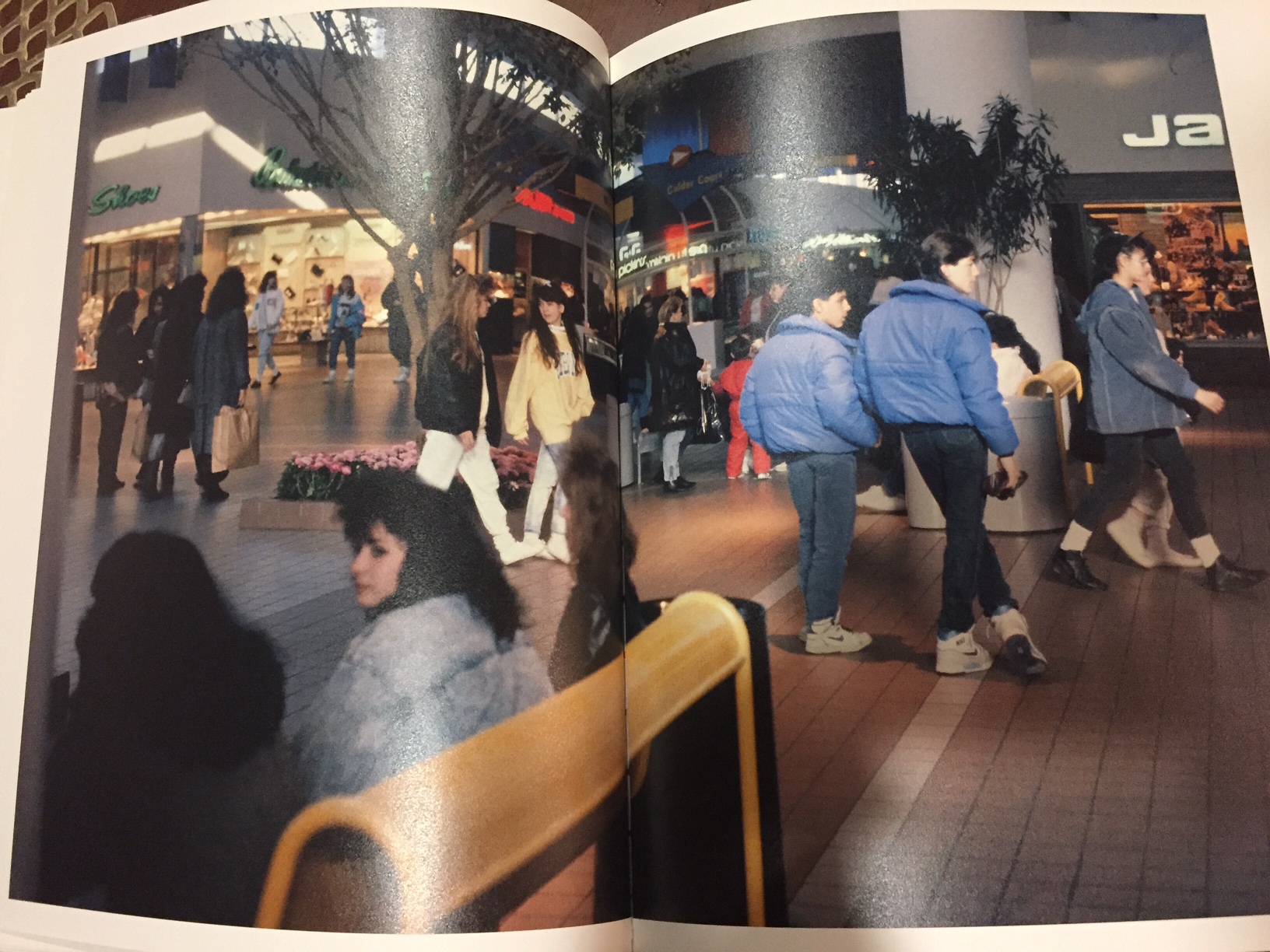

I shot the mall photos the summer before I found Ken’s book. Driving across the country to shoot in malls was my first real project. My second was shooting in a street market on Astor Place – documenting the vendors there. The mall shoot was an extension of a project that was done for a class, and the Astor Place shoot was also done for a class project. While my teachers appreciated the work, it wasn’t really seen much beyond those classrooms. I tired showing the mall slides to a couple of galleries, but I had no idea what I was doing and nothing happened. Even though I knew I wanted to make photos, I didn’t want to go to art school. While I was shooting the Astor Place project, I was also starting a band with friends and that became a pathway towards a life of making art.

Throughout the 90’s, I continued to shoot photos, documenting the bands in the scene that I was a part of. When I met Suki Hawley, we started to make films together and I began to increasingly focus my energy on that. While I published a book of my tour photos, I never really pursued photography as a “career”. About 20 plus years after I shot the mall images, I found a box of slides in a drawer and began to scan them. I put a few online and almost immediately they went viral. The response to the images was profound. When I shot them, I was a young photographer with more passion than skill, and they exist in a space between professional and amateur. They captured the feeling of the mall in a simple way that made people feel comfortable. Over the last several years, they have continued to go viral repeatedly. At the time, I quickly did a Kickstarter in order to raise funds to make a book- and that made them go even more viral. When that happened, I was approached by a designer named Peter Miles. He came over to my house to check them out. As he looked through the images, I was rushing around trying to finish our film “Battle for Brooklyn“.

Mr Miles told me that he doesn’t spend time on the internet, but that a friend of his had insisted he check these images out. As I rushed around, he went through my collection of slides and then offered to put out a book on one of his imprints – either through Rizzoli or Steidl. As a fan of photo books, I knew of Steidl, of course – and had even filmed a conversation of his with Robert Frank at the New York Public Library years earlier. I decided to go with Rizzoli because I had kind of a bad feeling about the “art world,” and on Rizzoli the book would be available in malls!- which only seemed fitting. He also made it clear that with Rizzoli I “would get paid”. While having a book published by the publisher whose photo books had originally inspired the work was very tempting (Robert Frank and William Eggelston and Gary Winnogrand), I really wanted it to be widely available. The very next day I went to the Hot Docs Film Festival with “Battle For Brooklyn,” and the first film I saw was “How to Make A Book With Steidl.” In the movie, he is shown as the absolute champion of artists.

As you might imagine, I texted Peter after the film and said, “it has to be Steidl”. The Kickstarter was still going on, and the next day Kickstarter made it “Project of the Day” which led to getting 100 pledges in an hour (this was 2011, so it wasn’t yet as huge as it is now). I talked with Peter about making an edition for just the Kickstarter backers, as I didn’t want to make them wait too long. He didn’t want that and agreed to push to get the book made sooner than later (as you can see in the article above, Steidl isn’t great about schedules).

Shortly after getting back from Hot Docs, the stress of dealing with our movie slammed me to the floor. I was literally stuck on my office floor for 17 days – unable to move. During that time, Peter came over to go over the images again. As I lay there, I told him the saga of each of our projects – how much effort and pain it had taken to get them made and the great resistance we faced as we tried to get them out into the world. He said, “you’ve just never gotten a break, have you?” It seemed in some sense that perhaps having my book published by Steidl might be a break. A gallery might even show the work, I thought.

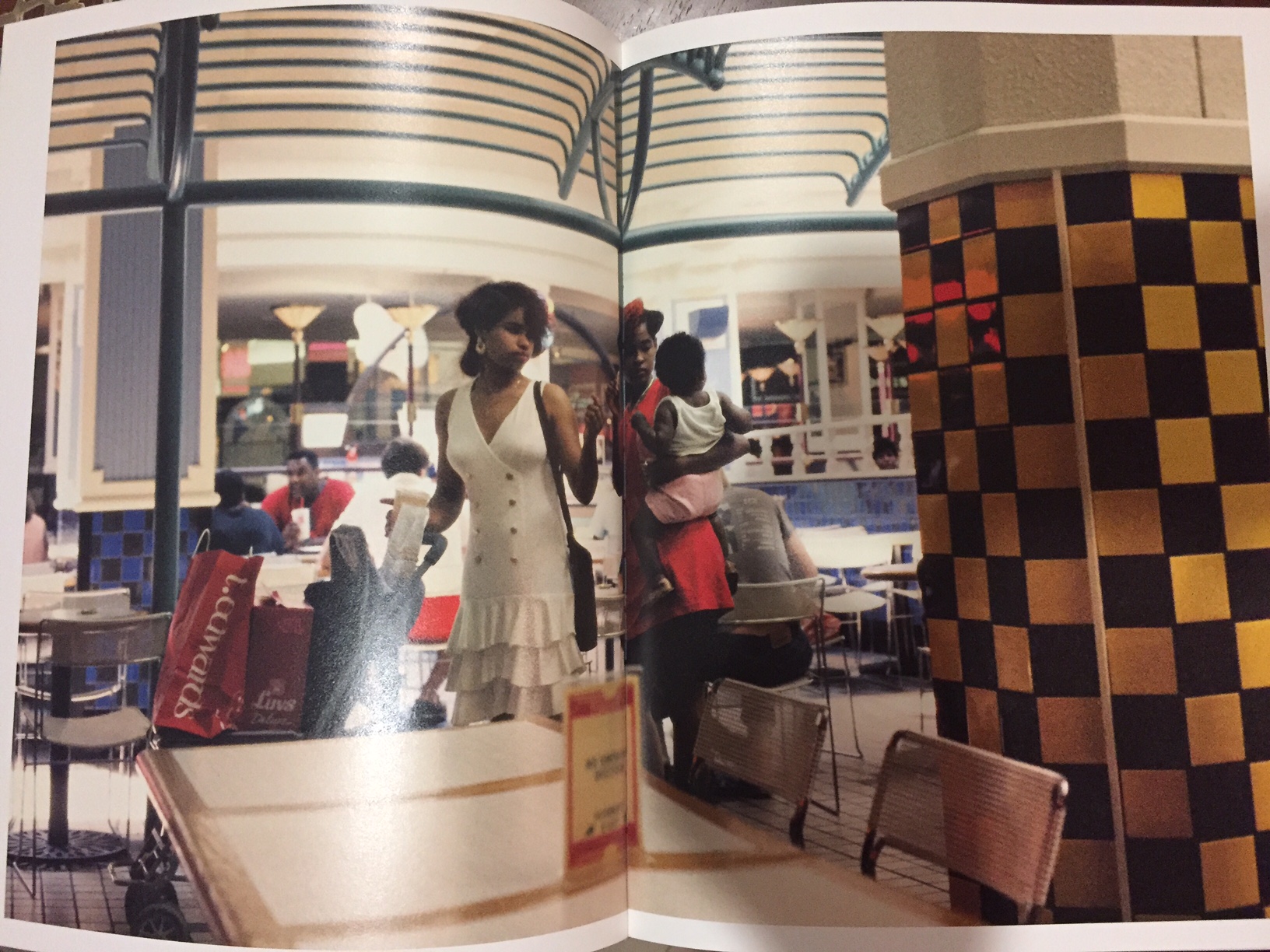

Peter is a very talented designer. He had a strong plan for the book, and we generally agreed about the images and the layout. A few weeks after we first met, I went to my childhood home and found two boxes of “reject slides” that contained a number of strong images. Originally, they were images that didn’t jump out, but their simple nature made them age particularly well. Sometimes it is the mundane images that have the most power when we look backwards. I chose out about 12 of these images, and showed the whole set to Peter. He chose the same 12, so we were clearly on the same page. The only concern I had was that he wanted double-page spreads for each image – the book would have to lay flat so there would be no gutter. The book was laid out and awaited a time to print.

Throughout this process I had no contact with anyone at Steidl at all. I never signed a document or got an email from the company. As the article makes clear, one of the great things about the Steidl process for artists is the focus on making them happy with the work. Unfortunately for me, I was never seen as the artist. As far as Steidl is concerned, Peter Miles is the artist that he works with to produce books. Peter was never anything but respectful to me, and he worked with me in the way that I had hoped Steidl might. Still, as far as Steidl was concerned, I did not exist. In I think the spring of 2013, I got an email from Peter. He was going to Germany to print several books with Steidl, including “Malls Across America,” and explained that it didn’t make sense for me to be there because it might take days or weeks till it got to press. I was disappointed, but I didn’t have any say in the matter really. I was new to this world of art, and I tried not to rock the boat. My Kickstarter backers were increasingly angry at having to wait, so I just crossed my fingers that it would happen.

Peter sent me some images of the book on press and it was exciting. A couple of weeks later, he came home and brought me the folded unstitched pages. The printing was incredible. It didn’t seem like printing but instead a direct transfer of the images themselves. It was clear, though, that it wasn’t going to be a lay-flat book, and I was worried about how the guttering would be. A couple of months later, I got a release date and I met with the publicist in New York. I told her that I would work to make it go viral and I urged them to be ready for it. It was clear that she didn’t really believe me.

As the time for the book approached, I gave a few images to some of the sites that had made it go in the first place- Buzzfeed, Retronaut, and a couple of others. It went nuts once again. The publicist was shocked- but she also got a lot going on for it as well. When I shot the images, I was a 20-year-old, somewhat shy kid. For the most part, I shot from the hip without looking through the lens. I did this partly because I didn’t want to interact with the subjects but also because I liked the idea that “chance” was involved. I didn’t want to make images that looked like they were supposed to look. Yet I did want people to be drawn to them. As much as I rejected the art world, I wanted the work to be accepted by it. I found it strange and frustrating that the work could go so viral, and touch so many people, yet it still had no respect from anyone in the art world. Like so much of the work that I have done as an artist, it was too “in between” for the system to know what to do with. When I was in a band, we were too weird for the people who wanted things to be straight- and too straight for the people who wanted noisy weirdness. Our films were too straight for the underground (though somewhat embraced by it) and too weird for the mainstream. Yet when people heard my band’s records they liked them and when we showed our movies people liked them. It’s always the gatekeepers who don’t know what to do with our work and that keep us on the sidelines.

As I said, in addition to my efforts, the publicist was able to get a lot mainstream press. She arranged for a great interview from Gizmodo. Their article had an Amazon clicker and it shot past 600 sales. They even sold 40 or so copies of Robert Frank’s “The Americans.” It became clear right away that the book would never make it to the stores because it would sell out on Amazon before it could reach them. I was under the impression that 3 thousand copies had been printed, but was recently told it was only 1500. I had to buy 400 copies from Steidl to give my Kickstarter backers. They wanted 25 a book, but agreed to 20 when I explained that I would already be losing a lot of money on the deal. Since I had sold the books on Kickstarter for $35, the shipping was going to crush any profit I might have made from the project- especially since so many were foreign and the shipping was as much as $30 for many of those.

When the books came, they were beautiful- but the guttering of the images was a big problem. 25% of the images suffered from this, and it got a lot of terrible reviews online due to this issue. However, the press in general was incredibly positive (probably because they mostly got the PDF). I got a copy of the book to the Wall Street Journal, and they did an amazing piece. Time Magazine put it on the best books of the year list and did a Lightbox feature. The only store in the US that I know of that got copies was Dashwood Books. They didn’t want to do a meet the author signing, so I went in and just signed all of their copies – drawing pictures in each one. I met with one guy who assured me that galleries would be beating down my door within a month. I tried reaching out to several, but couldn’t find a taker.

Because the book basically sold out before it hit most stores, the price shot up right away – The price was $36 on amazon when it was new, but immediately it went to $150 and stayed there. I was told they would re-print the book the next fall. I arranged to have Retronaut repost some images and their article got 186,000 shares. However, they didn’t re-print the book.

I was prompted to write this post because someone just tagged me on Instagram saying the only book they want is “Malls Across America.” I’m interested in doing another edition and several publishers want to do it, but part of the problem is I just don’t have the time or the resources to deal with it. I asked Peter to find out about royalties, but I think his deal with them is that they print his books and he gets some copies. He doesn’t expect money from them – he just likes to make the books and they like to work with him. He offered to pay me himself, but for me it’s really the principle of it. I find it so hard to understand why they couldn’t be bothered to ever communicate with me. Peter told me up front that if I did it with Rizzoli “the book will be widely available and it will be nice and you will get paid. But if it’s Steidl, we’ll get to do whatever we want, it will be beautiful, and somewhat exclusive and you won’t likely see any money for a long time.” My thought at the time was that they wouldn’t sell many books since they don’t have the kind of distribution as Rizzoli – and Peter made some books with them that had little chance of finding a market. I knew that the book would sell, so I didn’t see that as a problem. I should have asked more questions- but I was out of my league and hoping that it just might be the break I needed. I thought, if the book comes out on Steidl, then people will take me and the work seriously. That happened to some degree, but the work keeps getting stolen online, and I still don’t have a way to benefit from it.

In order to jump start another book, I recently wrote to the company to ask for the scans of my images. Again, I have no way to reach “the man himself,” and have had only the most limited contact with the company. I wrote to them explaining that since they hadn’t paid me for the 3000 books that sold, they should send me all of my scans on a drive. I got a terse response – clarifying that it was only 1500 books that had been printed and that they would print out the email and show it to Steidl. I’m not holding my breath. Peter told me a long time ago that it was very unlikely that they would share the scans with me, but I figured I should at least ask.

I’m not writing this to argue that Steidl betrayed me in some way. He did not. He never promised me anything and he printed a wonderful book. I wasn’t a part of their world when this project started, and I was not welcomed into it in when they printed the book. That should’t surprise me – it was my instinct in the beginning that my path was not in this world. When I read the recent New Yorker article about Steidl, which described his devotion to his artists and his craft, I meditated on how it made me feel. It did bother me that that system sees so little value in the work itself. In a world that is so focused on exclusivity, it shouldn’t be surprising that work which has populist appeal might be dismissed. A couple of years ago when the book was exploding in popularity and I couldn’t get the company to respond to me, I was frustrated and angry. However, at this point I can step back from the situation and accept it. I don’t appreciate being dismissed, but I don’t let it get to me that much either.

When I was younger, I had more desire for “success”. Part of that had to do with ego; the desire to be respected. A bigger part of wanting to make work and get it seen was a desire to have the ability to make work without so much struggle and compromise. However, over the years I’ve found that the struggle and the compromises create more complex and interesting work. The mistakes that often come from lack of budget and support force us to look at things differently. I turned 48 in February. I don’t feel old, but I have come to be more aware that I will not live forever. I think more about what kind of work I want to do, and I look backwards more at what I have done.

Over the past couple of years, a number of sites have run the mall images without contacting me, paying me, or crediting me. I have a lawyer now who helps me, but the piracy is rampant. The art world doesn’t think the work has value, but site after site sees value in using the images to create value for themselves. Just today, a friend tagged me on Facebook. Another website had straight-up stolen my images and made a slick slide show. I filmed it off the computer so I have documentation when I sue them. They don’t give me any credit for the work, but instead give credit to another site that stole the work and didn’t give me credit- as if to argue that it’s legal because they weren’t the first to steal it. While I am happy that people connect with the work, I am no longer happy that people steal it at will. It was my hope that having the book come out on Steidl would give the work a sense of legitimacy in the art world. One gallery that Peter Miles works with did put two images in a show, but neither sold. I have told many people over the years, “At some point, MOMA will acquire the whole set of images.” I still believe that. Go ahead and goole malls 1989 or malls 1980’s. Pretty much the only images that come up are mine.

No Comments