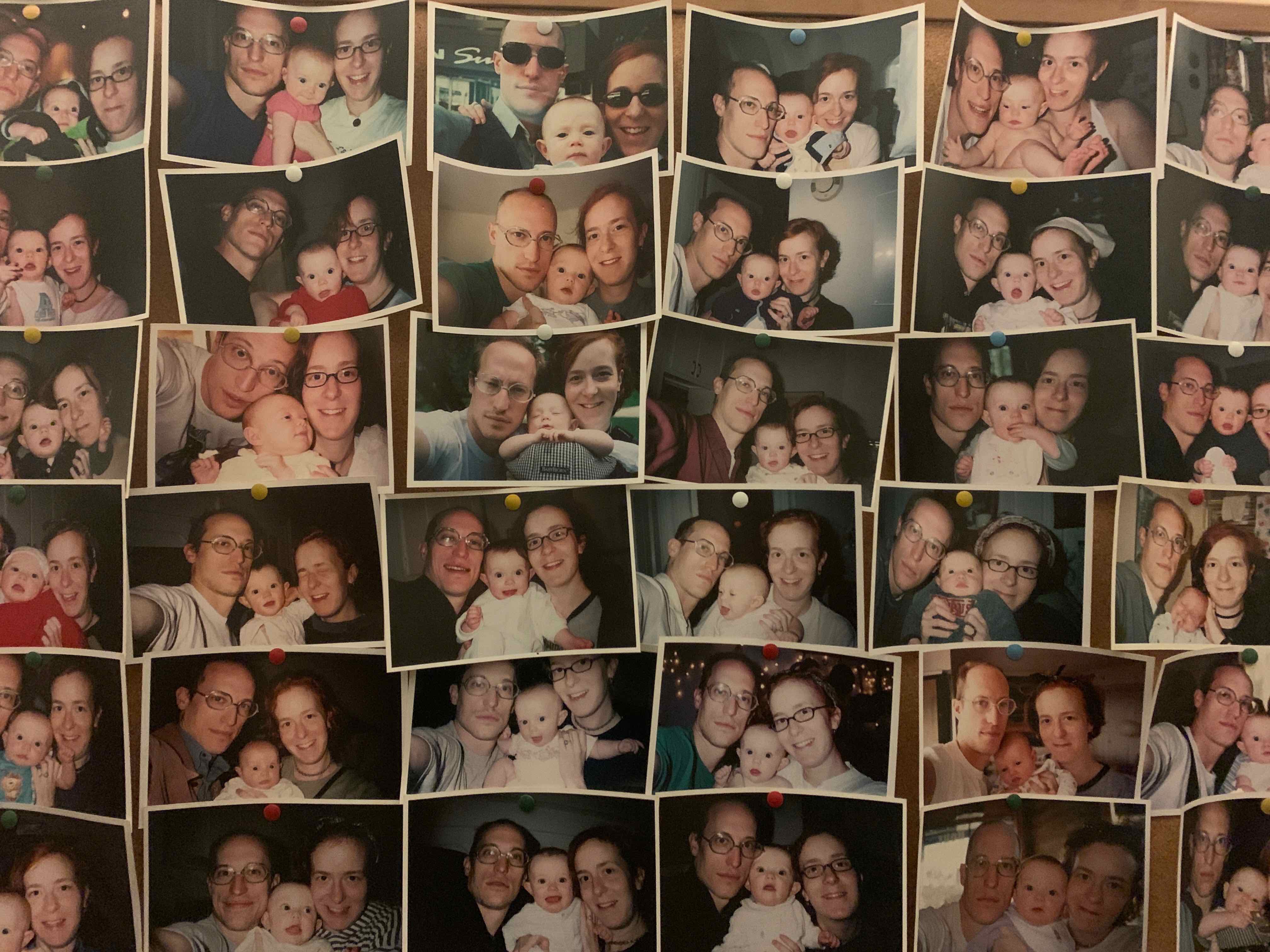

27 Jan Perfect Parenting

From the moment that we found out my wife was pregnant, all I could think about was being a good parent. OK, it wasn’t the only thing I thought about, but it always hovered there as something of primary importance – a profound shift in the way that I saw myself in the world. At the time, I began to reflect on things that I thought my parents had done right, and things that they had done wrong, and resolved to try to avoid the pitfalls they encountered. However, the patterns of behavior we learn as young children are often so deeply embedded that it’s hard to see where we begin and they end.

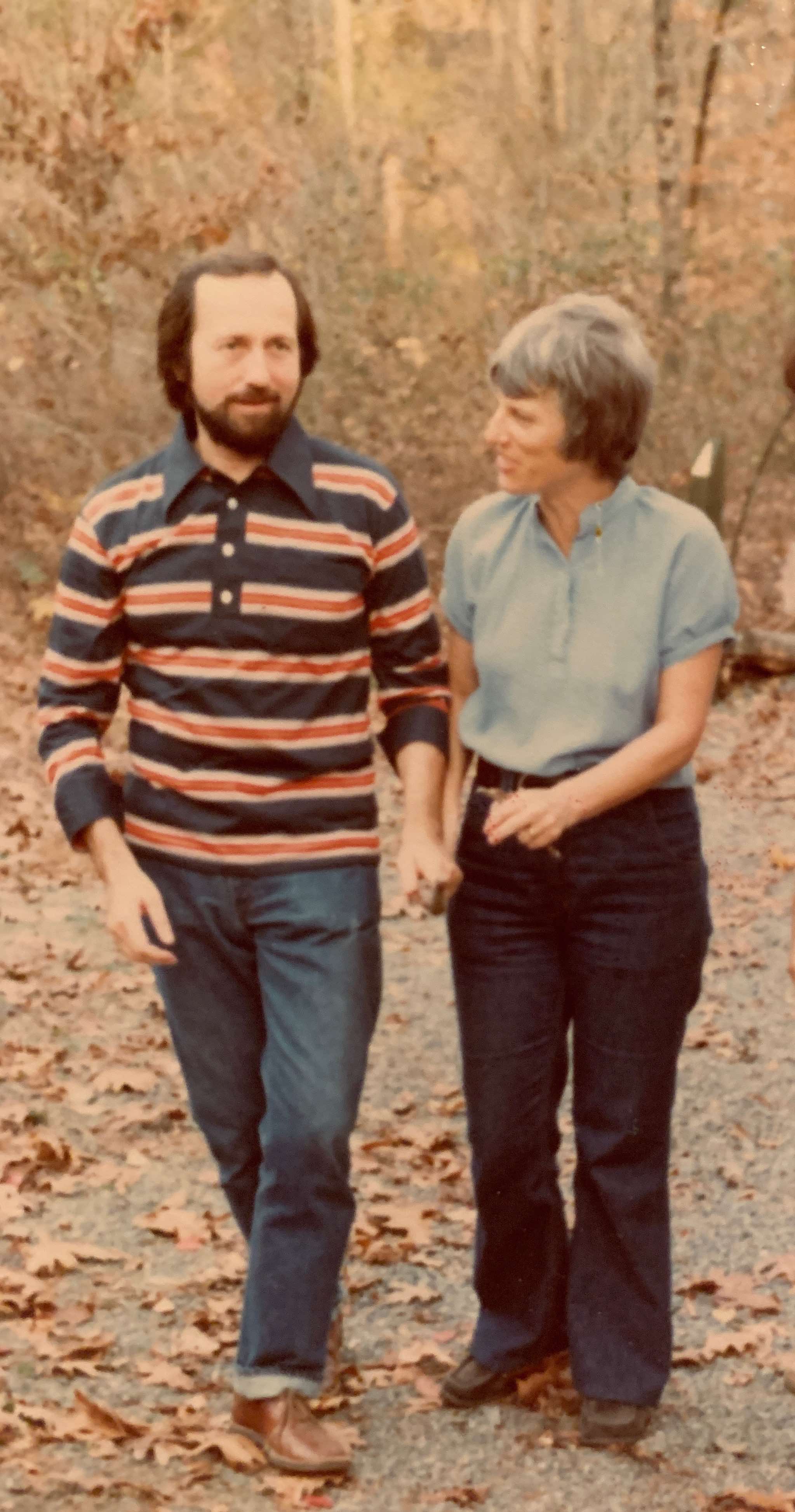

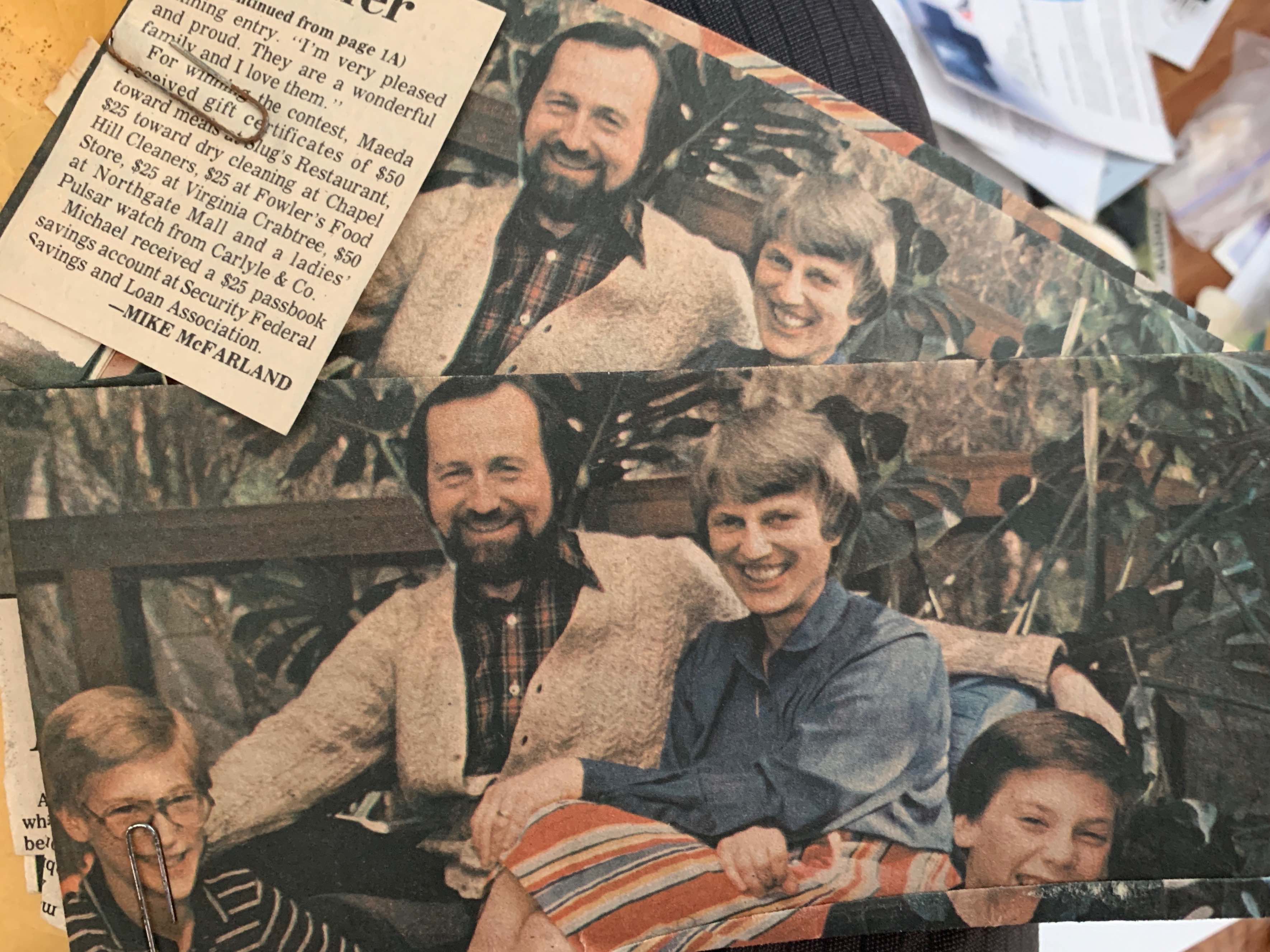

Like all parents, mine brought both their strengths and their shortcomings to the table when they began to intertwine their lives. Both of them were smart, intellectually curious, and had a desire to help others live better lives. My mother got her PhD in social work while my father got his in psychology. Both of them spent their entire careers as professors at the University of North Carolina. My mother did a great deal of research, while my father saw a few patients in private practice, and also led his department for many years. During the ’60s and ’70s, they were also very involved in issues related to social justice.

They did a lot of good in the world, and yet they were far from perfect parents. While no parents are perfect, part of the problem that I faced in dealing with their imperfections was that I was semi-conscious of a cognitive dissonance between their professional focus on healing through awareness, and their personal resistance to taking responsibility for their own behaviors. This disconnect has left me with a deep suspicion of – and resistance to – systems of all kinds. To be very clear, I have done a lot of work to find empathy and acceptance of their “foibles and pratfalls”, and this is not written with anger. Instead, I write as a way to gain more insight for myself and others as I try to unwind the deeper layers of how those patterns affected me. In “All The Rage”, our film about Dr Sarno, I talk about trying to break the chain of behaviors shaped by generations of trauma. It’s through coming to see these patterns that we can begin to break them.

My father was a loving and active parent who held us a lot, rolled on the floor with us, and laughed deeply. He also set nearly impossible standards for us to live up to in regards to performance in school. He expected us to act like little adults when we were barely able to act like kids. His expectations had to do with belief in our capacity to excel, but our inability to meet those expectations was stressful, and it affected our self esteem. He was doing the best that he could for sure, but even when we got older and could articulate the problem, he had a very hard time addressing it. Even then, I understood that his intentions were positive, but I was still enraged by his inability to listen, even when I was being calm and clear. Still, he worked at it, and the gift of his wedding speech, which addressed these ideas in a metaphorical way, is a tool that I constantly use to address my own resistance to change. My father died way too young, but thankfully we’d come to a much better understanding by the time he passed. The 14th anniversary of his death from being hit by a car is coming up this Saturday. I’ll be on an 8 hour drive and I’ll be thinking about him.

While my father set high standards, my mother’s deeply unconditional support for my creative output didn’t so much balance out my father’s expectations as get undermined by them. The gulf between their gazes was so great that it created a sense of distrust for both authority and my own worth. Again, especially in retrospect, I do not fault either of them for their actions; they were doing the best that they could. However, I can lean in to their unwillingness to change as leverage to make more room for change of my own life.

Individually, they both had profoundly positive impacts on me. As the cook, my father taught by example, and I learned a good deal from him. My mother was a passionate advocate for civil rights and women’s rights, and a great booster of her children as well as her colleagues. I picked up a lot from that, and it shapes my sense of who I should be in positive ways . My parents forced me to do a lot of things I didn’t want to do, most of which I’m grateful for in retrospect. I did not force my children to do very much because I remembered how much I hated being forced to do things. Sometimes I regret this – I think in the long term a little bit more pressure to lean into discomfort might have helped them develop a little bit more resilience.

While it was clear that my parents loved each other, their fights were numerous and often unrelenting. This is where the difference between their words and their actions was so profound. I would say that this, more than anything else, undermined my sense of trust for authority. When I was in college, I came home for vacation and got into a small altercation with my mother, who then held a grudge for the rest of my visit, kind of freezing me out, as she had often done with my father. There was no real resolve to it, and while we didn’t have many fights after that that I can recall, it created a distance that was only bridged many years later; and only when we were forced to deal with it because of my father‘s death. Still, being forced to deal with it meant that we began to have many more very difficult drawn out conversations (i.e. fights). My mother had a deep need for autonomy which manifested as a refusal to take responsibility for herself. For example, when we had a disagreement about something like the fact that her anxiety was causing her to have seizures, she would fall back on “you have your perspective and I have mine”. Three days after that refusal to address the problem, she had a seizure, fell, and crushed her skull. Thankfully, I had done a lot of work to learn how to respond to those difficulties. For years I would try relentlessly to get her to take my perspective. Ultimately, I learned to not repress my anger but instead to let it flow through, to respond rather than react.

The intransigence was still difficult, but working on having empathy for her inability to listen made it possible to get through these events without exploding with rage. Further, as her condition declined due to her increasing dementia, which was exacerbated by the fall, I leaned into accepting her where she was, and that ended up making her more comfortable.

As a parent, I consciously work to not make the same mistakes as my parents, while still holding onto the awareness that the patterns run deep. One time, when my oldest daughter was about five, she was really frustrating me and I got angry. My brother scolded me by saying, “you’re acting just like Dad.” I screamed back, “I am Dad!” He was right, and I found it very hard to untangle those patterns. Awareness helps, but it’s not a simple answer. Awareness lights a path, but seeing it doesn’t make it easy to move down it. Working on “All The Rage” did a lot to illuminate the path, and I haven’t rushed down it, but I can say with some confidence that I’ve moved down it quite a bit. I do work on being the best parent I can be, and I fail at it a lot. I also understand that the greatest failure is to accept those failures as a matter of course. Instead, I try to be thankful for them because they give me an opportunity to lead, by taking responsibility for those mistakes in ways that make room for change.

John Rosenthal

Posted at 04:25h, 23 FebruaryThoughtful.