07 Nov Professional Resistance

Ever since I was a small child I have chafed at doing things the way in which they are supposed to be done. Perhaps this is genetic, or a mash-up between nature and nurture; though I doubt that it was intentional nurturing that kept me on this path. In fact, I am sure that this is not the case because my father and I clashed a good deal about the paths I have chosen to take in life. Ultimately he came around to being fully supportive, but for years he would end our conversations with, “Write when you get work.” As a father myself, with a daughter who is even more resistant to power than I was, I understand him a little better, and I wish I could do more to help her understand how to avoid some of the mistakes I’ve made. At the same time, a lot of those “mistakes” led me in the right direction. There’s a balance between resisting control and being resistant. It can be done with more awareness making it a smoother and wildly more successful process than I engaged in.

Even though I thought that I wanted to be a photographer I chose to get a liberal arts degree. I didn’t have a clear vision for why I didn’t want to go to art school but instead had the sense that it would somehow “corrupt” my ability to be original. I also didn’t think of myself as especially creative and perhaps I was worried that I wouldn’t stand out, or fit in, in art school. I was probably right about that. It took me about 20 more years before I felt that I could call myself an artist, and even then I haven’t felt completely comfortable with that belief until recently. Also, after growing up in a college town I didn’t want to go to a school with a traditional cloistered campus so I went to NYU. In all honesty, it took me a little while to adjust to the city, but after a few months I found myself thriving on the energy of New York.

I was a photographer before I was a musician before I was a photographer before I was a filmmaker before I was a writer. I have never been a professional. Occasionally I have been paid for these different tasks, but more often than not I do the work because I feel that I have to rather than because someone is paying me to do it. I do not doubt that I wouldn’t have much trouble being paid for these skills if I did things a little differently. I am not blaming anyone else for the fact I am not a professional, because in truth, I have never wanted to be one. In some sense, I have always connected professionalism with corruption.

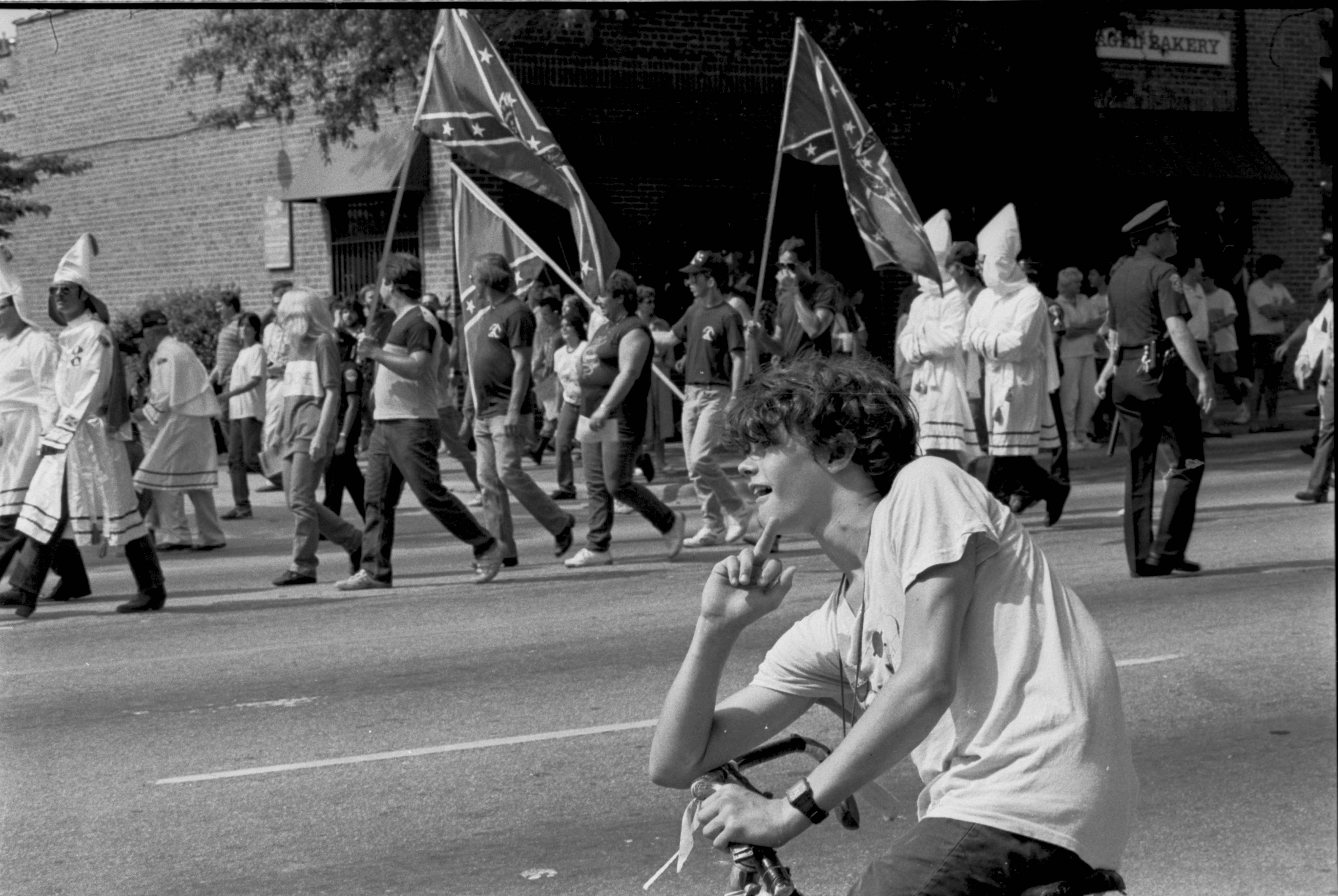

I believe that when we talk about corruption we think of it as a very obvious and present situation in which person A exchanges a resource (often money) in order to secure some sort of direct favor or privilege (a job or a project approval, a visa, etc). However, I equate professionalism with corruption in a very broad sense. I think corruption is much more subtle and often manifests itself as a kind of “willful blindness”. Person A looks the other way (often unconsciously) in order to hang onto a somewhat hidden benefit such as a privilege or a career; complicity in exchange for comfort. In an even broader sense, racism can be viewed in a similar fashion. Most people who enjoy some form of privilege due to their race, gender, or sexual orientation, have a hard time understanding this and often fail to even see or acknowledge it. Yet every day we are given concrete statistical examples of it. It is everywhere, and like almost everyone else I benefit from it, but also struggle with the negatives that it entails.

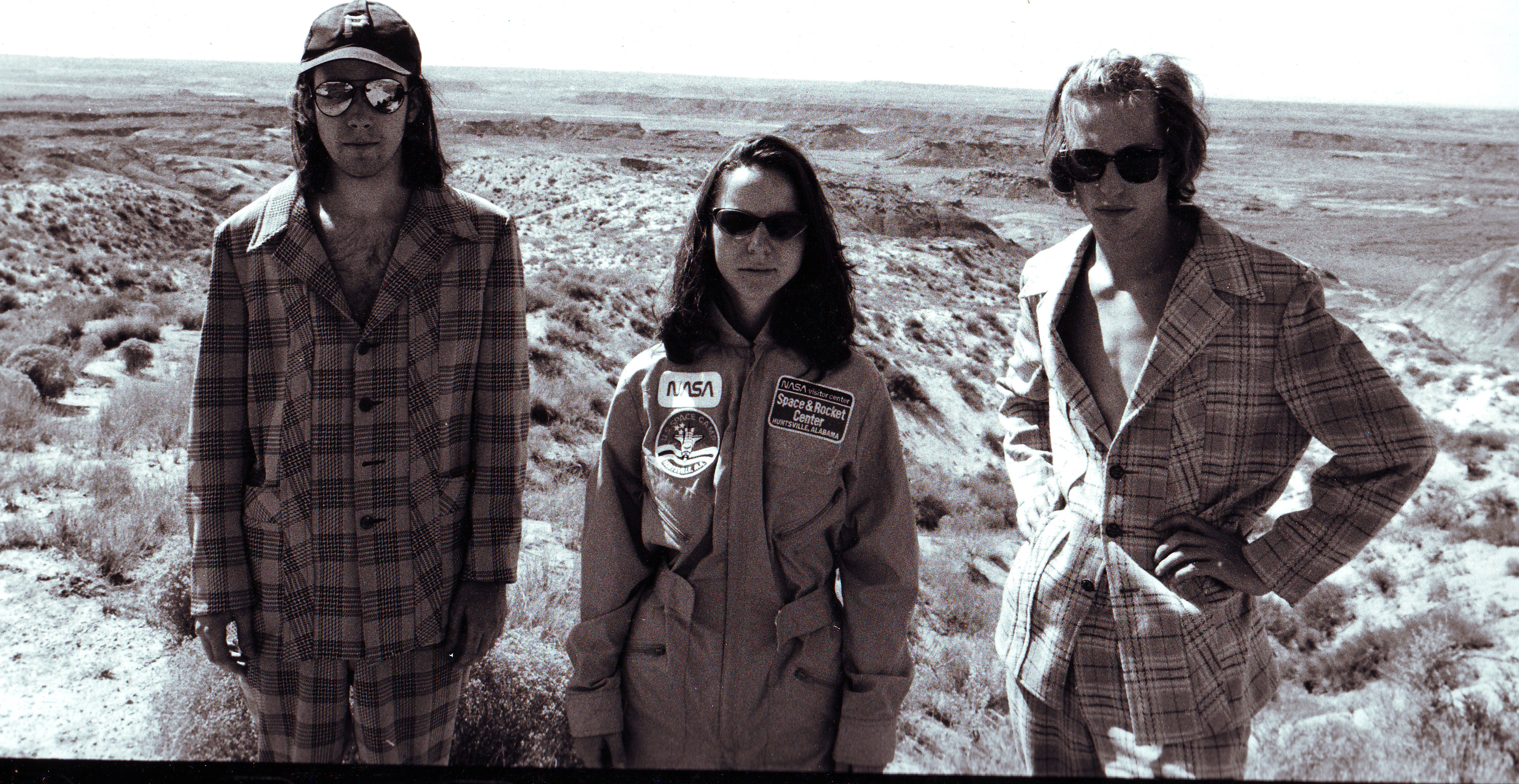

In our first film “Half-Cocked” Ian Svenonius turns to his “sister” and says “Haven’t you heard of etiquette? It greases the cogs of social interaction. You should try it sometime.” On some level etiquette is socialized corruption. We learn how to behave in certain ways and these ways become “who we are” to such a degree that we can’t even see it- that is unless we end up on the wrong side of that equation. In that case, it can be pretty enraging. Growing up as the child of college professors in a University town I was on the “right side” of that equation, but I still had the sense that something was wrong with the situation. I didn’t have a solid sense of what that meant, and I couldn’t really put it into words, but as far as I could tell there was something hopelessly corrupt about how it all worked.

Cake Sleepyhead from rumur on Vimeo.

During my childhood Senator Jesse Helms held sway over the political community in North Carolina. He famously stated that they should put a fence around my hometown of Chapel Hill and call it the zoo because it was seen as a hotbed of liberal activism. I wasn’t a big fan of Jesse Helms, and I didn’t think of my town as a zoo, but I too had the sense that something was out of balance even if I couldn’t put it into words. Chapel Hill felt like an island and there was something that was almost too soft and comfortable about the life that my parents had built for us. Again, while I had no way to describe why it bothered me, I did react to that feeling in a myriad of ways- including often following the path of most resistance.

In college I was a religious studies major- not because I wanted to get a Ph.D. but instead because I happened to be drawn towards classes like Theism, Atheism, and Existentialism. I completed the major without meaning to. While in college I spent most of my time going to rock shows and record stores. I was a terrible musician but I was still drawn towards being in a band because I didn’t want to be a consumer; I wanted to be a participant.

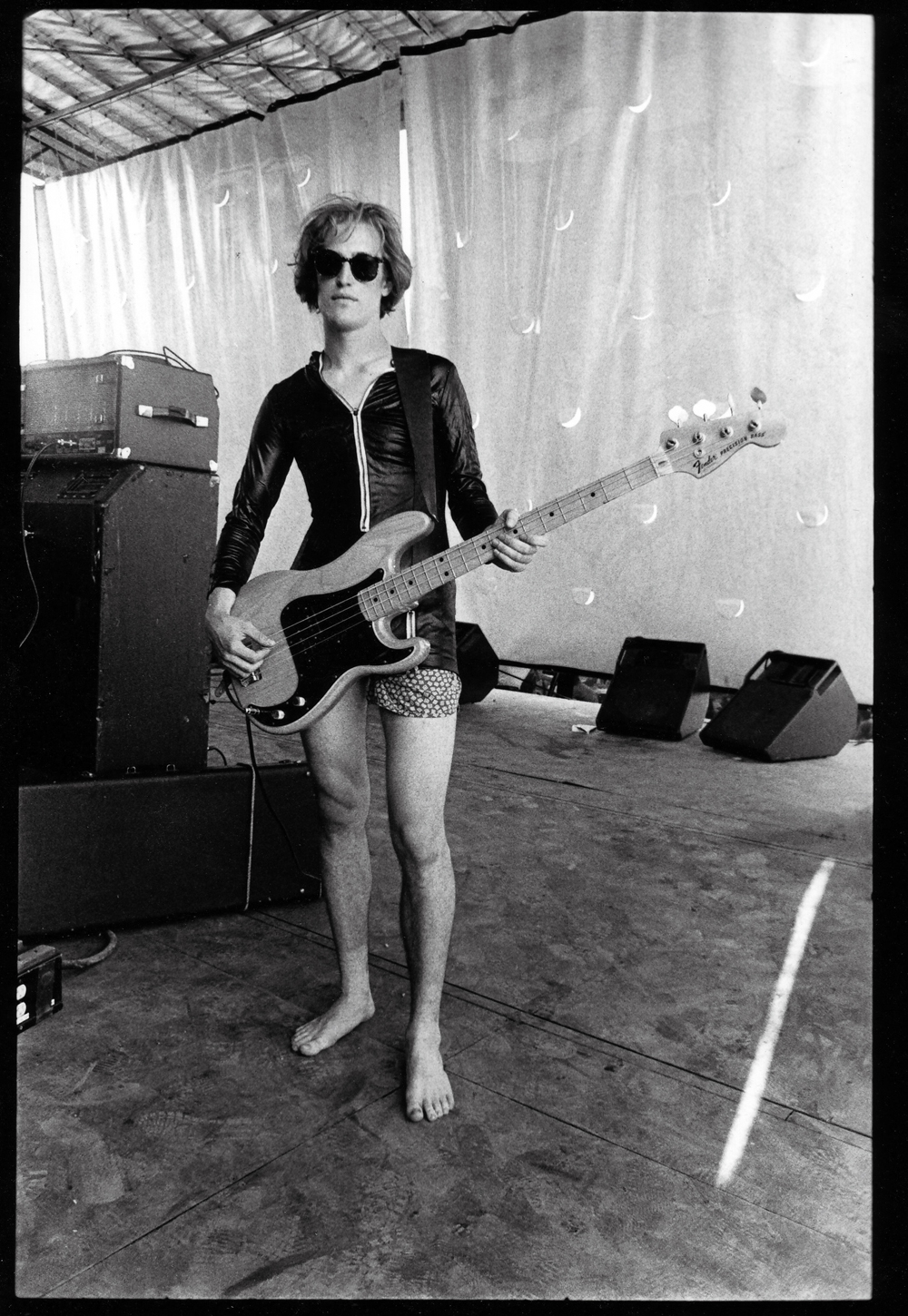

In the voiceover that starts our film Radiation we had the character say “The problem was that I was drawn to music about problems.” This wasn’t actually a problem for me, but it was true about the music that I was drawn towards. I liked songs that felt wrong and I didn’t want to know how I was “supposed to play” my bass. I ended up playing in a band for a decade, and by the point that I did know how to play, it had lost a lot of its charm. It was never going to be a job for me but it had become a grind.

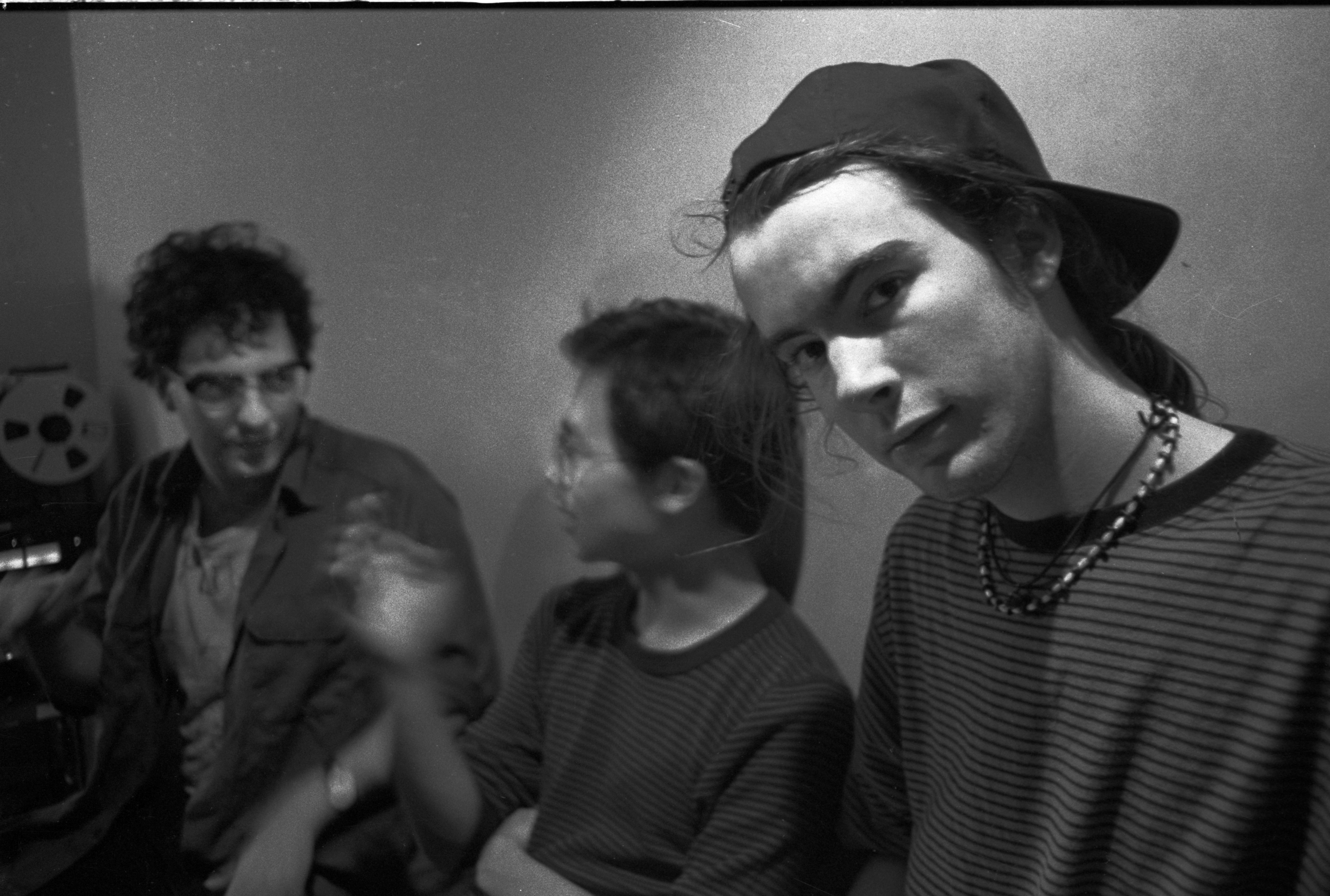

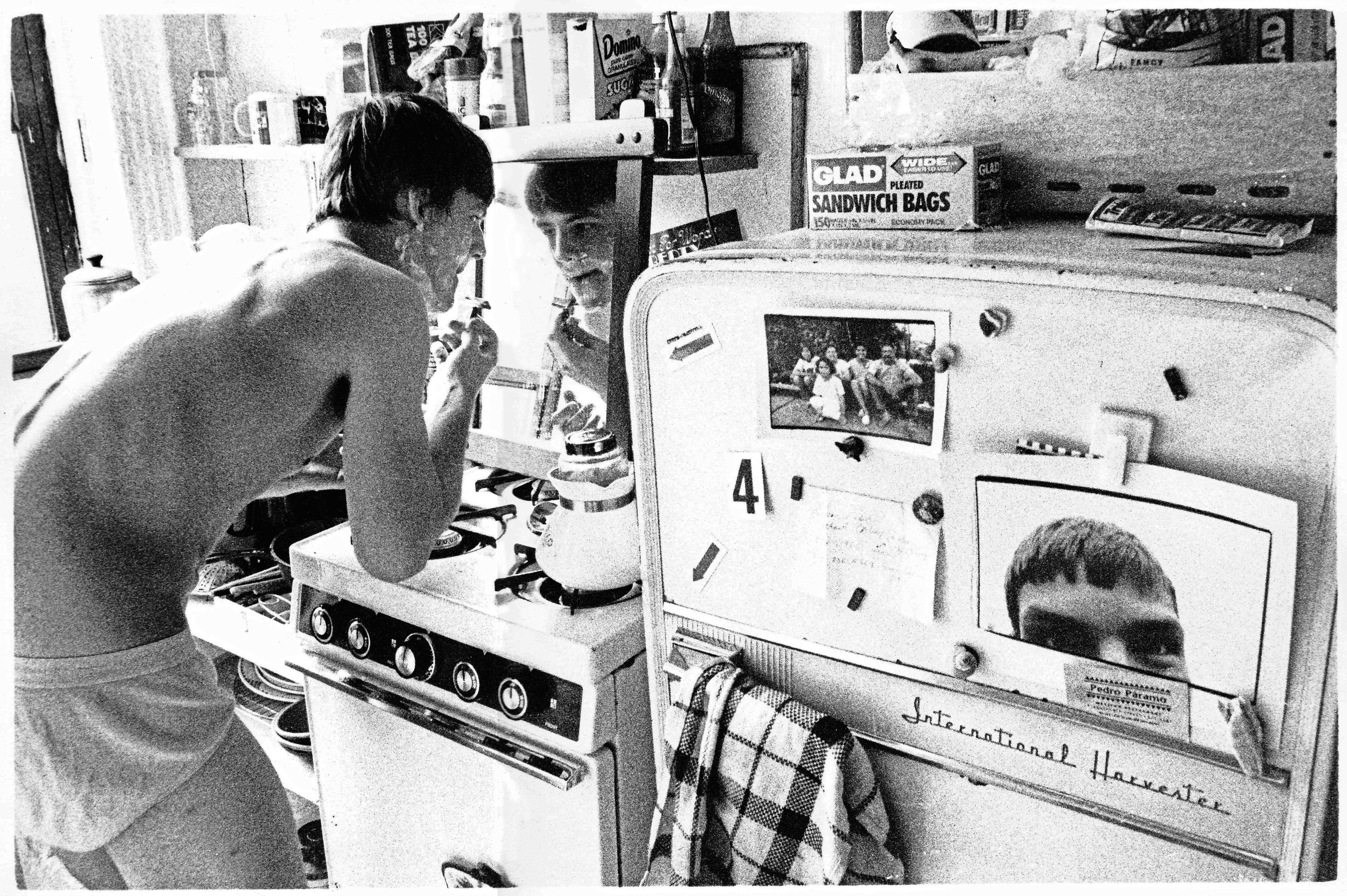

While I was in the band I was also documenting that world; first as a fan and then as a musician. I got a few jobs taking pictures of bands. Every time it was a job I strained under the pressure. I absolutely hated it. Most of my best band promo shots were grabbed right after they played. I chafed against expectation and every time I had a big job I totally blew it. If I was being asked to create something that conformed to an expectation I froze up. A couple of times I was asked to show a portfolio. I gaffer taped images to the front of a case I’d found in the street. I didn’t get a lot of jobs that way- but I also knew that the jobs that I might get with the “right kind” of portfolio were not jobs that I would be any good at.

I tried to show my work to a few gallery people but since I hadn’t gone to art school I didn’t know the drill. I didn’t have a studio and I didn’t make the kind of photos that jumped out at people. I generally just wanted to capture things rather than make things happen. That led to images that felt a bit mundane at the time, but have a certain verisimilitude 20 years on. I think the same is true of our films and in some ways the music that my band made. Some people saw the value at the time, but I do think a lot of it holds up.

I’ve been thinking a lot about these ideas as we hustle to put the final touches on a 12 year documentary project about a doctor that’s also become something of a personal narrative. The old pictures, and videos come in handy. A good part of the narrative deals with how these outward struggles to find a way to get my work seen, and to create a life outside of being a “professional” can be hard on the psyche and the body. Groups have norms for a reason. Professional standards aren’t all bad by any means. However, for someone who chafes against the standards, it can be a struggle. I haven’t gotten to the bottom of my deep distrust of power, structures, and institutions, but I have gotten a little bit more comfortable with myself. I’m gonna call that a success.

No Comments