17 Apr Response Ability

When was the last time you found yourself really upset about something you couldn’t control, like a cancelled flight, or a misplaced car reservation? Did you find yourself yelling at the person at the desk or on the phone? Or, did you simply accept the fact that you’d get on a plane at some point, or behind the wheel of a different car? In the past, I found myself getting enraged in some of these situations. More recently, through a lot of effort, I have slowly learned how to respond rather than react when situations deviate from my expectation. Things have not only gone more smoothly, but the end result of these interactions has been more positive as well.

There is a profound difference between being responsible for something and having the ability to respond. In our culture, we have a hard time differentiating between the two. Responsibility involves judgement; notions of accountability and fault/blame. Having the ability to respond involves a sense of agency. The ability to respond feels very different than being at fault. The difference between the two has a lot to do with perspective. When we react as if someone is at fault then they usually respond defensively. If we are aware of how those interactions play out, we can regulate our reaction, making it possible for us to respond without a sense of either blame or defensiveness. This in turn can make a lot more space for dialogue. In this case, we’re examining the concept from the point of view of interactions between two people. At the same time, this kind of dialogue can also be one that we have with ourselves.

If we extrapolate this reality inwards and focus on our perspective on the world – as well as our expectations for ourselves – we can gain a great deal of insight in the difference between reaction and response. A reaction is seemingly automatic; and it takes place when we are on “auto-pilot”. However, even in a car, auto-pilot is based on a series of algorithms and patterns that are based on learned experience. Here’s where perspective comes into focus. Some of those patterns have to do with how we view ourselves and how we view the world. If we view ourselves in a negative way, and don’t have confidence in our own abilities, we might find that we automatically undermine our ability to achieve our goals. If we hold ourselves to a high standard we might expect the same from others. If they don’t live up to our expectations, this can be enraging. Even if we don’t express that frustration with words, it’s likely that we express it with energy, and often that energy is more confusing and more powerful than words. The more aware we can become of what we are feeling, the more able we are to regulate how we respond to those feelings rather simply react to them.

If we view the world as a dangerous place, we are more likely to react defensively when we feel challenged. If we focus a little more intensely, we can see that this defensive reaction has to do with not only physical threats but also emotional ones. Most of us have heard of the flight or fight response: our bodies automatic response to danger. The algorithms that control our reactions to the world are programed both through our genes and through our experience. Our DNA can change under extreme stress, and these changes can be passed on to our children. Further, the way in which we are raised also affects the way we react to threats. In the wild, we understand those threats to be largely physical. In other words, our body releases stress hormones that help us move more quickly and focus more intensely on a threat. However, when that threat has left, we shake off the fear and go back to a kind of stasis. This process is run from a small almond shape part of our brain called the amygdala. Our senses constantly scan the environment for threats and if the amygdala encounters something it understands to be a danger it goes into action. However, it relies on the thinking brain, or frontal cortex, to develop those reactions. Essentially after a scary situation, like almost getting hit by a bus, the amygdala checks in with the cortex to asks if buses are dangerous. If there is a communication that buses are a threat, then every time we encounter a bus, the amygdala floods the body with stress hormones to prepare to either fight or flee. However, the cortex can intervene. If we become aware of this reaction, then we can re-train the brain to stand down by letting it know that buses aren’t scary- but walking in front of one while on our phone is. The cortex can make an executive function decision to be more presently aware, which takes some of the strain off of the amygdala.

This is where the ability to respond comes in. The more aware we become of our bodies’ physical responses to perceived threats, the more agency we have to respond to those moments. The more we pay attention to our reactions to the world, the more we can see how often we physically react to emotional threats. Fight or flight responses are really geared for threats that might cause us physical harm. Unfortunately, the amygdala has no means of differentiating between a physical and an emotional threat. With awareness, we can turn our attention to re-training the brain to respond to emotional threats rather than to react. This is what I mean by response ability- or developing our ability to respond or react.

Given that our world is increasingly crowded with the kind of threats that our fight or flight system wasn’t designed for, it’s not surprising that our bodies have a hard time handling the stress of modern life. If we react to each of these emotionally difficult situations by flooding our system with stress hormones designed to face a physical threat, it can be very confusing to the body. We are built to face these threats and then stand down, allowing our body to reabsorb and release the chemicals and hormones used to ready us for conflict. If we stay in this state of readiness, it’s akin to being inside a city under siege. It’s hard for resources to get in and waste to get out. In times of peace, cities can focus on streamlining operations and making time for joy. When we understand this and we do the work to re-train the brain to respond rather than react to threats, we find it easier to navigate the ups and downs of life. If we can change our perspective, we can change our life.

“All the Rage”

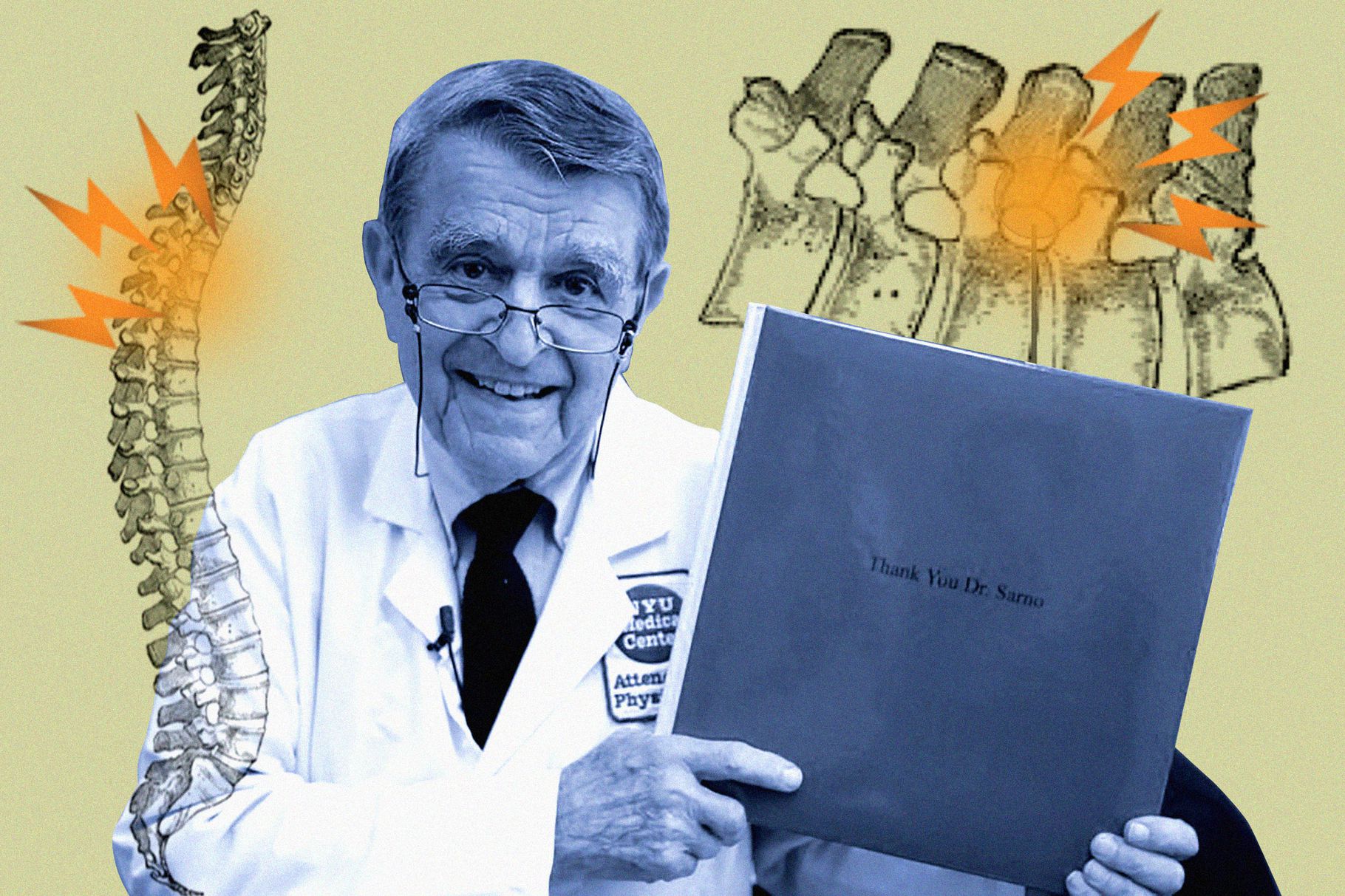

I have spent the past decade immersing myself in trying to understand this to make a film, and to heal myself. My partners and I made “All The Rage,” a documentary about the profound connection between the mind and the body in regards to health. Our film focuses on the work of Dr John Sarno, who made a connection between people’s back pain and the repression of their emotions. His understanding was that we often repress our emotions because, at a very young age, we learned that it is dangerous to express them. Further, he postulated that since we unconsciously view these emotions as dangerous, our brain causes pain in order to distract us from the emotions, because they seem more dangerous than the pain. Illuminating this connection gives people the ability to respond with more emotional awareness. Unfortunately, most people respond to this idea with a defensive posture; rejecting this understanding as saying “it’s all in their head” or that they are somehow “responsible” for their own pain. This is understandable. Who wants to feel like they are being told that the pain is their own fault? Yet, this defensive posture is part of the problem.

Dr. Sarno came to understand the problem when none of the treatments he had been taught for back pain were successful. First he looked for data to support the standard treatments and could find nothing convincing. He then checked his patients’ charts and found that 80 percent of them had a history of 2 or more other issues that were commonly understood to have a mind body connection, or a relationship to stress; skin issues, colitis, ulcers, headaches, vertigo etc. Armed with this knowledge, he talked with patients about what was going on in their lives. He found patterns of behavior that made it clear people were often pushing aside feelings in order to avoid conflict. When he helped patients make the connection between the pain and this process, they often got better. Over many years he developed a deeper understanding of what he dubbed Tension Myositis Syndrome (TMS). Myositis means muscle, and later he changed it to Tension Myoneural Syndrome when he recognized that nerves were drivers of the problem. Many people now use TMS to mean The Mindbody Syndrome. I think of it as simply being human.

A key thing to understand about “unconscious emotions” is that they are hidden from our present understanding. In many ways, they become a part of “who we are,” so illuminating these patterns can feel like we are losing our sense of ourselves. This gets us into complex discussions of the ego and the unconscious. For our purposes, I’d like to keep it simpler and just point out that “unconscious emotions” are also unconscious emotional reactions. For example, I’d like everyone to think for the ways we often react to the demands and expectations of our parents. My parents have both passed away. I loved them, yet I also had a lot of difficulties in dealing with them. My father set unreasonable expectations for me, and this created conflicts between us. It led to me reacting to him with rage more often than I’d like to recall. As I detail in our film, once I had graduated from college and committed to making art and being in a band, he ended every one of our weekly conversations with “write when you get work.” No matter how many times I told him that I was working and that his comment was demeaning and that it pissed me off, he could not stop himself. At one point, I threw my heavy phone across the room and went phone-less for months. It was an unconscious reaction. If I had done a bit more work on dealing with those emotions, I might have been able to respond without that kind of rage reaction. Frankly, now I have a little more empathy for him. I can see that his comment came from a place of fear. He feared that I would not be able to take care of myself if I didn’t get a graduate degree, or a stable job. Unfortunately, because he communicated this desire to help me from a place of fear, it pushed me into a defensive posture. In some ways, he was right. My life path has been much more difficult both emotionally and financially because it was outside of most systems. However, if he had had more capacity to listen to me he might have been able to offer guidance that was useful.

I think a lot about balance, and visualize conversation in relation to how we speak and listen. If we listen in a defensive way, we create resistance that people often react to by becoming more forceful. In general, neither party is fully aware of what’s going on, and a series of reactions can lead to increasing levels of conflict. When we listen without resistance, even when someone is pushing into our space, we can often avoid conflict. Unfortunately, often when we try to listen without resistance, we are unconsciously repressing those reactions and the person we are dealing with may react to that energy without realizing it. It can take a lot of work to shift from a reactive posture to a responsive one. However, the rewards are quite powerful. When we can get to a place of more emotional awareness, we experience more peace.

The process of making All the Rage involved dozens of rough cut screenings to help us understand how the film was connecting with people. At first, those who were more skeptical wanted more facts and information. Since they had trouble accepting the very simple idea that the mind and body interact in ways that can have long term negative health implications, they wanted – even needed – scientific proof. Unfortunately, because they were so skeptical, no amount of data was going to convince them and the more we put in, the more skeptical they became. Eventually, we came to see that we had to make the film personal and emotional. Soon, we cut out almost all of the data because it was something that people would get stuck on. Once they got involved in the story of how emotions affect us and how our emotional patterns are difficult, yet not impossible, to break, they began to make connections to their own emotional patterns. In short, any effort we made to “prove” Dr Sarno was correct was met with a defensive reaction. The same is true of trying to get the film in front of people. So, we have learned to offer it up as a gift without any expectation. That in itself has been a practice of becoming more able to respond. It has not always been easy. The reviews in both the NY Times and the LA Times personally shamed me for being in the film. My first reaction was to feel some shame. However, I was able to think through it and recognize how absurd their reaction to a film that was. It is explicitly about how our culture shames us for having emotions, which leads to the repression of those emotions, which leads to pain and illness, and yet they were so resistant to that idea that they doubled down on that process. Once I as able to be more fully aware of my reaction, I was able to respond with less emotion and more empathy. I thought about the fact that most people are reviewers precisely because they are judgmental – and that they are judgmental because they want to reflect outward rather than inward. The film is designed to ease people towards looking inward, and if they are avoidant of that, the defensive response would be to shame the person who pushed them in that direction. In the end, it was most frustrating because it made the film that much less likely to reach people.

No Comments