20 Nov Technology Spiral

This morning, I started to write a post about the evolution of humanity’s relationship to photography. Then, kind of like technological innovation, it spiraled off in several competing directions. That’s not such a problem for me, but it does push up against systematic expectations of communication; something that I typically struggle with. I’m going to go ahead and start with photography, but I want to be clear that this is only partly about photography and technology, both of which have had mutually impactful relationships with ideas and culture.

Photography and Technology

The development of photography fundamentally changed our relationship to the self. Previously, Narcissus was enraptured by his reflection in water. The mirror made us more intimately connected to ourselves, and photography increased that impact because it made us more connected to not only our expansive and historical selves, but also to our ancestors. Perhaps it’s not accurate to say “more connected”, but instead, changed our sense of connection to ourselves and our ancestors.

At its inception, photography was not for the masses, but when Kodak went into high gear on affordable personal photography things began to shift dramatically. When photos became moving pictures society once again began to shift. Fairytales and myths have a distinctly different impact when turned into moving images. One only has to think about “Birth of a Nation” and “Triumph of the Will” to imagine the ongoing depth and power of these stories turned into pictures. The stories that these two films embedded into mass consciousness still have an effect on deep seated ideas that thread through our culture, ebbing and re-emerging over time. Nearly 40 years ago I shot photos at a Klan march in my hometown. At the time, it felt like a last gasp of an outdated form of racism. With Trump’s campaign and election victory these ideas have once again begun to emerge publicly in ways that feel shocking, yet undeniably present.

The birth of the personal computer, like the personal camera, has had an epoch making impact on our lives. The unfolding flow of technological innovation that this power unleashed has been unprecedented in regards to business, art, culture, education, politics, and war. For now I’m going to focus on art and culture.

Both digital sound and image capturing, in conjunction with the emergence of the internet/social media have had profound impacts on our relationship with images, both still and moving, as well as in connection with sound. Ultimately an exploration of this impact is connected to our relationship to ideas and self awareness. In many ways these technologies have made us more connected. At the same time that they have created opportunities for connection, they have also exponentially increased our sense of division as well. Algorithms that confirm our beliefs, and connect us to others who believe similar things tend to also make us feel more resistant to, and divided against, ideas that undermine our beliefs. The unintended consequence of a greater sense of belonging is a greater sense that people who believe ideas that we don’t believe in, are our enemy.

For the past 25 years my partners and I have primarily worked on documentary films. As I will discuss below, technology made this more possible, but over time, that same technology flooded the zone with content, which made it harder to find outlets for our work. During that period we made 4 political documentaries. These films became increasingly less able to find funding or bring in revenue. They also, when looked at as a series, document an increasing sense of division within the realm of partisan politics, the increasing impact of money and media consolidation on political discourse, and an ever increasing sense that the voices of citizens were being lost in the echo chamber of politics. This last issue reached an inflection point in 2011 with the explosion of the occupy movement, and this impact was writ large on the results of the 2024 election. We’ll get to that in a moment.

Digital Media and Streaming Changed Everything

I remember how profoundly the prevalence of prosumer video cameras impacted filmmaking. When Suki and I made our first movies, we had to shoot them on film because that was the only way you could get a movie seen or distributed. Beta cameras existed, but they were expensive and cumbersome and they definitely looked very much like video which differentiated the footage from film. small digital video cameras came out that had broadcast quality images. It really changed everything. All of a sudden there was a steady stream of more complicated and interesting documentaries, and people started to experiment with lower budget narratives shot on video. It made it possible for us to start making documentaries. Our first one got shortlisted for the Oscar. At the time it was not such a crowded field of films that qualified to be submitted. Now it’s a deluge. Also, at that time we weren’t allowed to tell anyone.

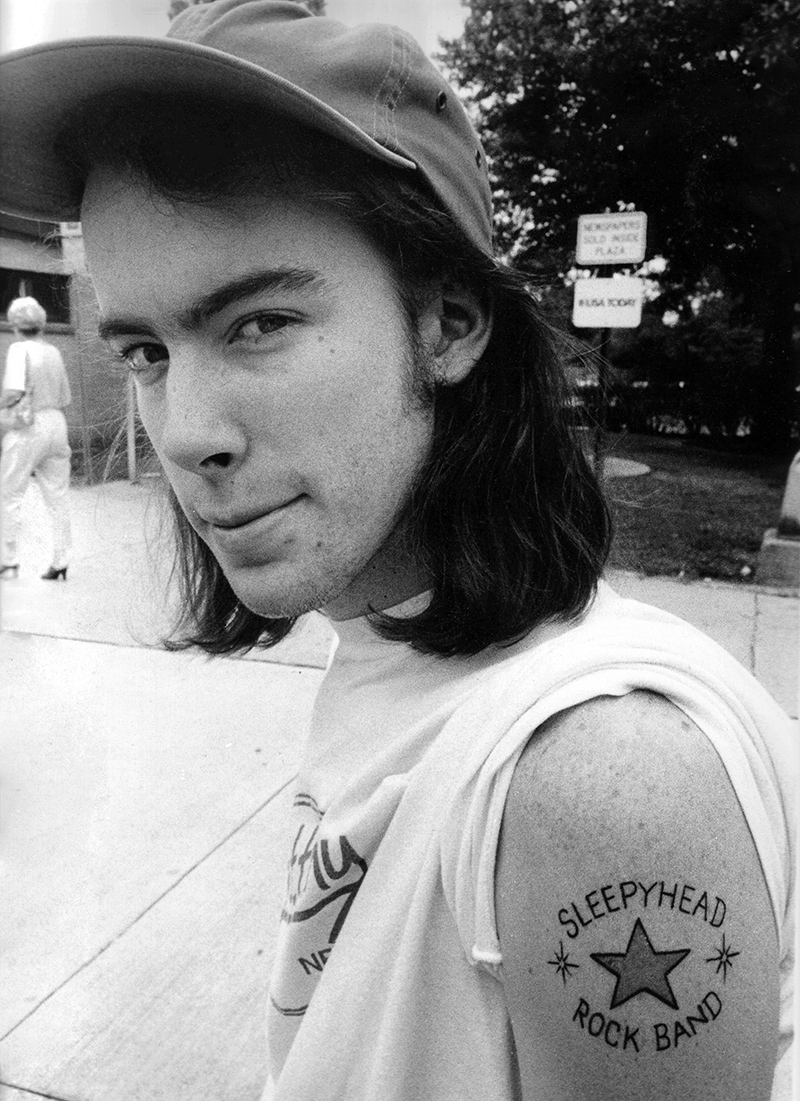

Before we made films, I was in a band, and the availability of lower cost recording possibilities, like cassette based 4 track recorders, made it so much more possible for people to experiment with music. That sparked a Lofi revolution, which coincided with an explosion in underground connectivity, and communication. It was a very exciting time. My band recorded a demo tape six months after we started to learn how to play together and, a few months after that, it was getting played on college radio stations even before we had pressed a single. When we finally did put out a single I imagine that there were about 500 singles produced that year within that underground community. A couple of years later that had risen to 5000 and all of a sudden it had become overwhelming. After a decade in music I was burnt out and overwhelmed. I can’t imagine the pressure there is on kids today to be aware of every new trend in their increasingly networked superstructures of loosely tied connectivities.

The Internet and Social Media

Technology has always impacted our lives. When we started our band, the Internet existed, but it was not a part of our lives. When I was in college, we did not yet have email or Internet access. It was only about three or four years later that AOL opened up the possibility of having email. So, Trying to book a tour pre-Internet was not very easy, but the connections that were made were deeper and more rewarding.

I started out talking about ideas related to photography, and the proliferation of images, partly because it was through photography that I first started to step on the pathway towards becoming an artist. When I started a band I also started to document the music scene I was a part of. Typically systems want you to be a part of one of them, but for me all of the forms of art are interconnected. In many ways I see film as the highest art because it involves storytelling, writing, image, sound, music, structure, design….. all of the arts. For me the path to being an artist was to have a hand in every aspect, including the distribution. Everything that I have done has been adjacent to systems but never really a part of any of them in a grounding way (except for music on some level).

As I worked in all of these forms, I intersected with ways in which they were all profoundly impacted by technology, and that impact changed the very nature of their existence and the relationship between artist and audience via distribution and community. I want to highlight how these technologies created access to tools for creation and distribution that opened up amazing levels of possibility. They also opened up a flood of content, which then diluted the possibility of sustainable distribution. Over and over again, excitement about access and possibility was rapidly overtaken by tech that allowed an ever smaller group of people to benefit from the outpouring of content. That has been combined with a public that has been overwhelmed by possibility. People spend more time trying to figure out what to watch than they do watching. More often than not my wife and I try to find something for half an hour and then just give up. People also listen to the same 100 songs on Spotify because the algorithm knows what they like. Sometimes those algorithms lead to new discoveries, but rarely in a way that creates a sustainable path for the artist.

While social media made it possible to connect with people we hadn’t seen in a while, it has also flooded us with a kind of overflow of loose ties that can be overwhelming. New tech has made it that much harder, and less likely, for us to connect in more concrete ways. We are all too overwhelmed to process the flood of information, ideas, images, and content that we are barraged with each day. These forces have made it almost impossible for us to look outside of our bubbles and tend to limit our ability to be thoughtful.

I think this is a big part of the reason we are looking at a completely unprecedented political situation. Trump’s underlying argument that the power structures that were in place needed disruption. I agree that this is true. I don’t think the best way to get there is destruction. However, if our institutions get destroyed we might ask – how do we build them back better?

We all Think Differently

My mind works in somewhat fractured ways, and while this following idea might not seem related to our political climate, I think if you allow yourself to zoom out with me you’ll understand both the context of these ideas, and why they are of particular interest to me. I don’t know exactly why, but I have always been very suspicious of systems, but also wary of those who want to destroy systems completely. In short, I think the systems are necessary in regards to warding off chaos. However, systems have a tendency to get too entrenched in their own rules and methodologies and blind themselves to important information that might suggest shifts or changes.

I was never completely rebellious; I liked punk rock but never dressed like a punk. I hated school, but I got good grades. I challenged my teachers, who sometimes called my parents, but I never got suspended -etc. Like Groucho Marx, I never wanted to be a part of a club that would have me. This meant that even though I loved taking pictures, I didn’t want to take pictures the way they were expected to be taken, and I also didn’t want to compete with other people for attention or validation. We live in capitalism. This is not just a monetary system, it is also a cultural system. Even before people began to talk about artists as “brands”, Andy Warhol made his mark by living in the space between art and commerce. In some sense he wasn’t doing anything new, but much like Donald Trump has done with politics, Warhol exploded the art system by mocking and embracing it at the same time, and then bending it to his will. His seemingly offhand statement that everyone will be famous for15 minutes in the future becomes more profoundly true with every click of the clock.

I started to think about this idea in relation to photography this morning. I was thinking about my own photography. I’ve always had crappy cameras. I think that for me the image has always been a spark for ideas rather than a focus on aesthetic qualities. I love well made and powerful images, but I feel resistant to trying to find a decisive moment, or define the value of image making in that way. For me images that are less perfect are more interesting. I can appreciate Steely Dan but I would much rather listen to Sonic Youth. I want art that makes me think rather than work that feels perfect and organized. That’s my preference, yet I absolutely appreciate both. However, in photography, even within the realm of social media, gate keepers still control lots of access to audiences. This doesn’t mean that it’s not possible to find an audience for one’s work. However, even though my mall images have gone wildly viral dozens of times, and I have made two books that are widely sought after, I have found it almost impossible to find a “reputable gallery” that would help me to get my work in front of collectors who create real world value for these kind of images. Since I don’t exist within that system it is hard for that system to see my work as having value.

Social Media

My daughter Fiona is like me in so many ways; maybe a little bit too much, which led her to be resistant to me in the ways that children often try to avoid being their parents. Like me, she had a lot of self doubt and did a good amount of invidious comparison. With social media that became very problematic. She’d open instagram and see steady streams of cool art that made her feel terrible about herself. In large part she has overcome that impulse, but it still crops up. Social media has a tendency to both connect us, and, partly due to capitalism, leads us to compete for scarce resources of attention, money, and livelihood. AI is only increasing that problem

Politics

The same algorithms that deliver us artwork or music that appeals to us also tends to create little pools of connection that trap us. This isn’t a nefarious plot, but it is the way that the platforms can hold us within their realm. The more we stay in their realm the more they can sell things to us, and a lot of what they sell to us is the sense of value they create by connecting us. When they connect us due to interest, aesthetic alignment, intellectual agreement, or political fealty, the more power and influence they gain. They then sell that power and influence to advertisers. We are caught up in a psychological shitstorm experiment and when we look back at the last few election cycles we can see the impact of these forces.

Back to the Movies

When we started to make documentaries our first one was quite political, but it was also steeped in the underground music world, within which we had made our first two film. The main character of that film, “Horns and Halos”, was an underground publisher who had put out books for a lot of musicians we knew. We had not met him when we found out that he was going to re-publish a discredited bio of GW Bush that had been pulled from the shelves after it was revealed that the author was a felon. To make a long story short, the book had a hastily added afterword tat alleged the younger Bush had been arrested for cocaine and that his father had gotten him into a community service program to hide that problem. The sources were anonymous. The new publisher ran into problems and the book got pulled again and was ultimately re-published yet again after Bush won and at a press conference he revealed that the source was Karl Rove, Bush’s hard hitting campaign manager, and known dirty trickster. The “discredited author” trope had killed the story- after that it was forever untrue. So, from a practical point of view it makes a lot of sense. However, a month after revealing that news, the author killed himself. That made the movie more interesting, but it was also devastating. That election was complicated and the dirty tricks emerged during the recount where Republican assets sowed chaos during the count and ultimately it was the hanging chads on the ballots that mark a steep decline in the validity of democratic institutions. All three of Trump’s Supreme Court nominees were lawyers in support of Bush in that election. The long arc of history leans to supporting those who fight for “noble” causes.

A few years after making that film we started a documentary about a community fight in NY. It was a nearly decade long examination in how one party rule (NY was so solidly democratic that the primary tended to decide the winner – yet very few people voted in primaries relative to the general election so a smaller number of people determined representation) creates incentives for mild levels of corruption. This kind of corruption is less about money passing hands than agreeing to vote as told in order to maintain one’s position. In any case the subtext of the film was that the community was sold out to the benefit of a developer. Shortly after we finished that film the Occupy movement started. While we were shooting Horns and Halos the WTO protests had roiled Seattle. Those protests were largely built around the idea that globalization, while bringing down prices, was also bringing down wages and aiding in the hyper concentration of wealth. As we shot Battle for Brooklyn we saw how the banking crisis led to a bail out banks, without much punishment or correction. The rallying cry at Occupy was “Banks got Bought Out We Got Sold Out”. People felt let down by the government. Libertarians and the Left found common ground in that space. Trump swooped in and gathered up that rage to seize victory in 2016.

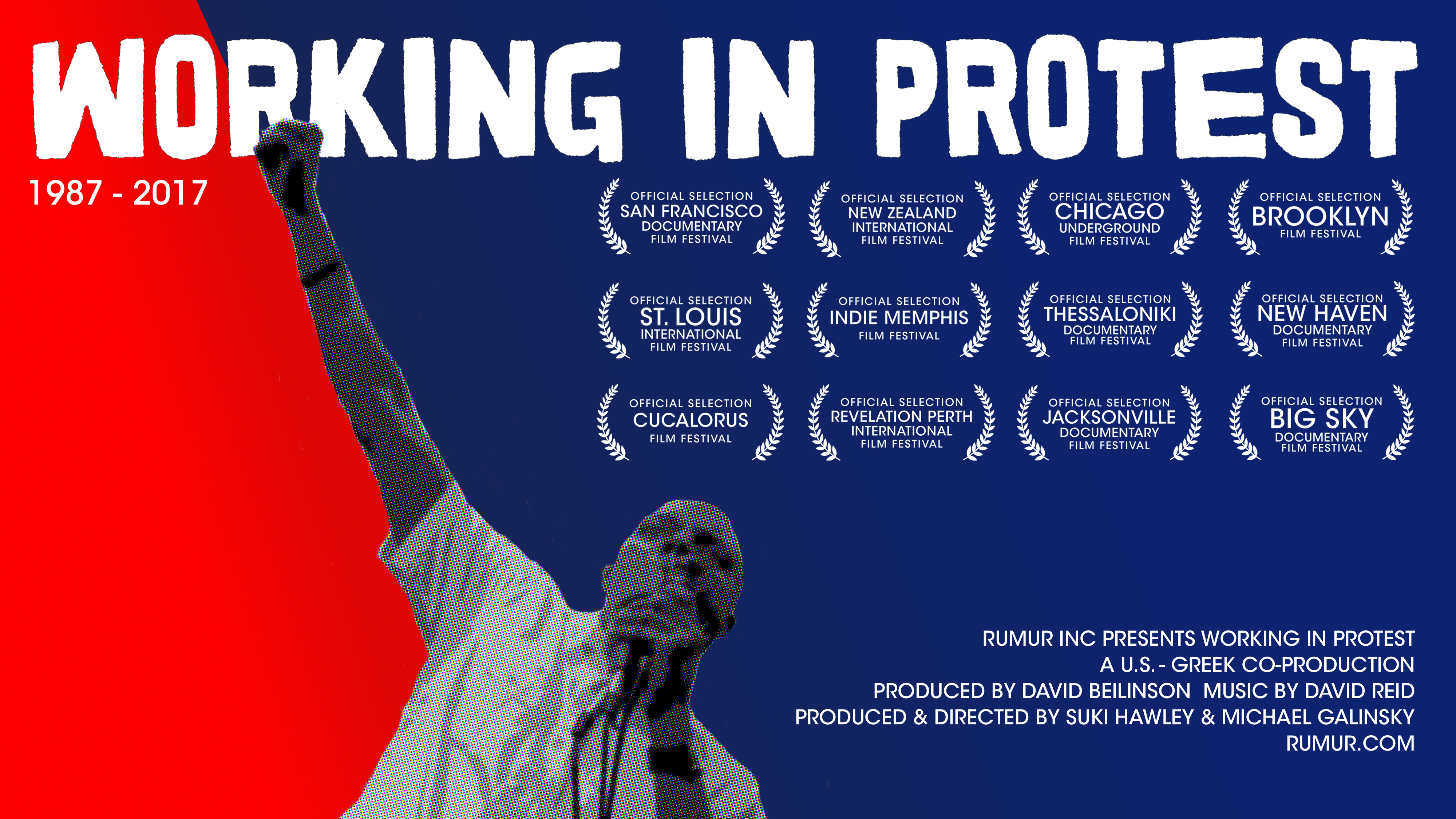

After Battle for Brooklyn, I had begun to shoot a great deal at Occupy. I continued to shoot at protests in North Carolina. I filmed at a Bernie Rally and a Trump Rally. Both pulled in ecstatic audiences. I filmed outside of a Clinton rally which did not have the same energy of excitement. Bernie and Trump represented change. Hilary represented the status quo. During that campaign we began to take all of the short work we had made around politics and wove into a film called “Working in Protest’. That film painted a picture of an increasingly divided and fractured America.

When we made our first documentary “Horns and Halos” we had no budget. We got no grants and we did all of the work ourselves. We struggled to get it seen at first because our last day of shooting was the day before 9/11 and the surge of patriotism after that made it impossible to raise questions about the government. A year later when the wars were in a quagmire that shifted a little bit. We were able to put it in theaters and sell it to many different TV stations around the world. We actually made money. With Battle for Brooklyn we once again self distributed and got good reviews, but we made no sales to television despite getting shortlisted for the Oscar. We made no money. With Working in Protest we went to a lot of festivals and after putting it up on Vimeo on Demand we had 2 rentals for a total of 3 dollars in revenue. Still, we think it’s an important document and is even more impactful right now because it paints a vivid picture of the problems of hyper partisanism.

Working in Protest finishes at the Inauguration of Donald Trump. Like most of the movie it is an observation rather than a judgment or argument. We didn’t expect Working in Protest to make us any money. Instead, we saw the value in creating work that has more value in the future than in the moment. When work is observational it has less heat or draw. However, years later it has much more power in its simplicity. Work that has advocacy intentions tends to reveal a bit less about what a situation feels like in the moment because the stronger point of view shapes how it’s viewed. The difference is subtle, but tends to be more obvious in the future.

We continued to do that work documentation as Trump’s actions led to more protest. The protests got angrier and the division grew. We filmed a series of protests centered around the fight over a Confederate Statue on the campus of The University of North Carolina, in my hometown of Chapel Hill, NC. These protests were spread over two school years. The protests largely happened in the fall. After the first year we found out students were making a film and we gave the class all of our footage. When the protests started up again we filmed and quickly realized that we could weave those protests together as we had done with Working In Protest. This film was not about the issues that were driving the conflict over the statue. We did not interview anyone or provide much context. The film was called The Commons because it focused on what was taking place in the literal common space. There was a lot of rage and almost no possibility of discussion.

We showed that film at a festival only weeks after the base of the statue was removed. The response was powerful. At our third screening a filmmaker who was involved in the film that was started in the class that we had given our footage to led a protest of 25 other students demanding that we never show the film again. Their argument was that while it was legal to film, it wasn’t ethical, because we had not gotten permission from the protesters. They also said we had done our work in secret, along with many other complaints. The only thing that I felt safe to clarify was that we had shared all of the work in the film publicly as we made it and that we had seen the film she had made, and that it had many of our scenes in it exactly as we had shot them- which belied the claim that we had done our work in secret, but also that they seemed to have indicated it was ok with them because they had shown it at a festival as is. Her response was that the had to remove it because it was “polluted by our white gaze”.

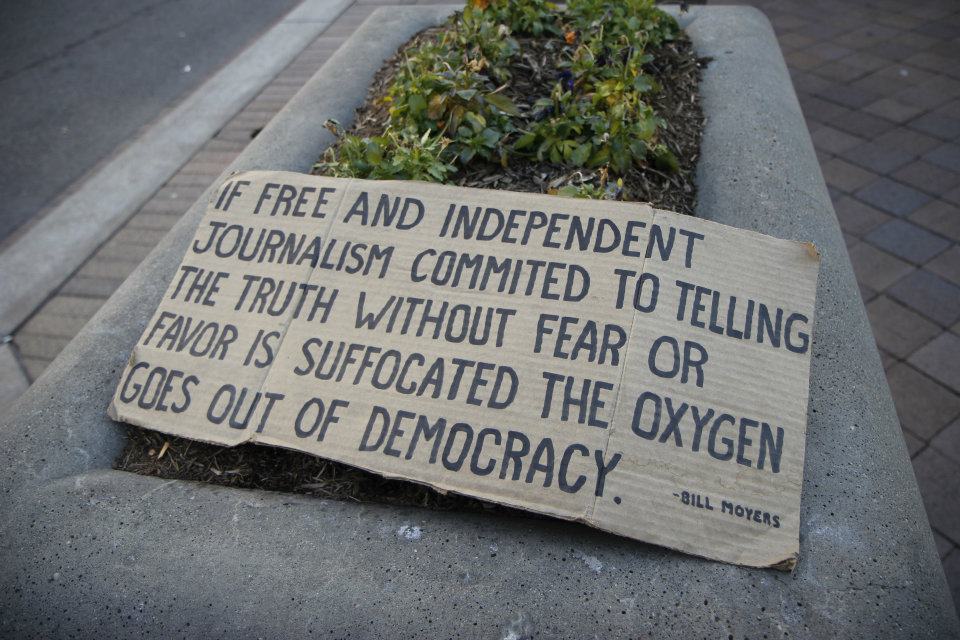

The goal of the film was to drive conversation about what to do about the near impossibility of our division, a division that seemed driven by a desire to divide us. So, given that the film seemed destined to drive only more conflict, and the fact that no one in the documentary community was willing to make the point that free speech and the freedom to film public events is important to democracy, we pulled the film from festivals. However, now, after the election it seems more important to have these discussions and we are trying to figure out how to go about getting the work seen and discussed.

Forward

We are definitely at a cultural and political inflection point. The Right gets in line behind a leader and the left fights over details. A good deal of the rage that Trump was able to use to his advantage was driven by the assertion that the left – via “the woke mind virus” wants to censor us. I had no interest then, and no interest now, in embracing the right’s rage. However, it is hard to describe how debilitating it was to get canceled in the way that we were. It also points to a problem that needs to be addressed. If we are going to move forward as a culture we are going to have to dial down the rage and listen more. Rage is Blinding. In fact one of our most recent non-political films is called “All The Rage”. It’s about how our own rage blinds us from feeling, or seeing, the traumas that we have buried deep inside us. The fear of experiencing these uncomfortable feelings often causes us great stress that manifests as pain and illness. When we sit with those feelings and that rage we learn to let some of it go. Once we do that we are more capable of being less reactive- which makes it possible to listen and communicate with others who do not already agree with us.

No Comments