01 Nov The Semmelweis Effect

WHEN HEALERS ARE AHEAD OF HISTORY

While historians credit Louis Pasteur with articulating the germ theory of disease, many others came before him who began to tease out the ideas that led to this deeper understanding of illness. One of these doctors, the 18th century physician Ignatz Semmelweis, spent much of his time taking care of women who developed puerperal fever (childbed fever) after giving birth at a hospital in Vienna. The hospital where he worked had two delivery areas. In the first, physicians came to deliver babies after spending mornings doing surgeries as well as autopsies; many of which were done on women who had died of puerperal fever. The second birthing area was run by midwives who solely focused on helping with childbirth. Semmelweis noticed that a higher rate of women who gave birth with a doctor died of fever, and that only half as many who went to midwives did (16% compared to 7%). He wondered if there was a connection between doctors moving from surgery and autopsies to entering the delivery room and the illness. He ran an experiment where he had doctors and midwives wash their hands before helping with delivery for a year. Subsequently, the percentage of women who died of fever went down to around 2% in both groups. However, despite the evidence that the washing of hands somehow prevented the disease, his colleagues rejected his findings as being akin to witchcraft. While this kind of resistance to change can be seen within all systems, it also appears that Semmelweis was not a great communicator. According to one article:

Semmelweis with his undiplomatic behavior made more professional enemies than friends in Vienna and had to leave for Budapest to work in a city hospital for the rest of his life. Semmelweis published a book “Etiology, the concept, and the prevention of puerperal fever” in 1860, after 13 years of his study. The book had an unwelcome response; it was criticized for poor language and unprofessional writing style. Semmelweis could not tolerate the criticism and suffered with bouts of depression, rage, paranoia, and forgetfulness. He ended up in a mental asylum and died in 1865.

History is often written by those with the most power, as well as the best communication and social skills. Those who are better able to walk a fine line – gently challenging systems that they are a part of rather than attacking the system – often have more success at changing a system than those who are not.

DR. SARNO AS A MODERN DAY SEMMELWEIS

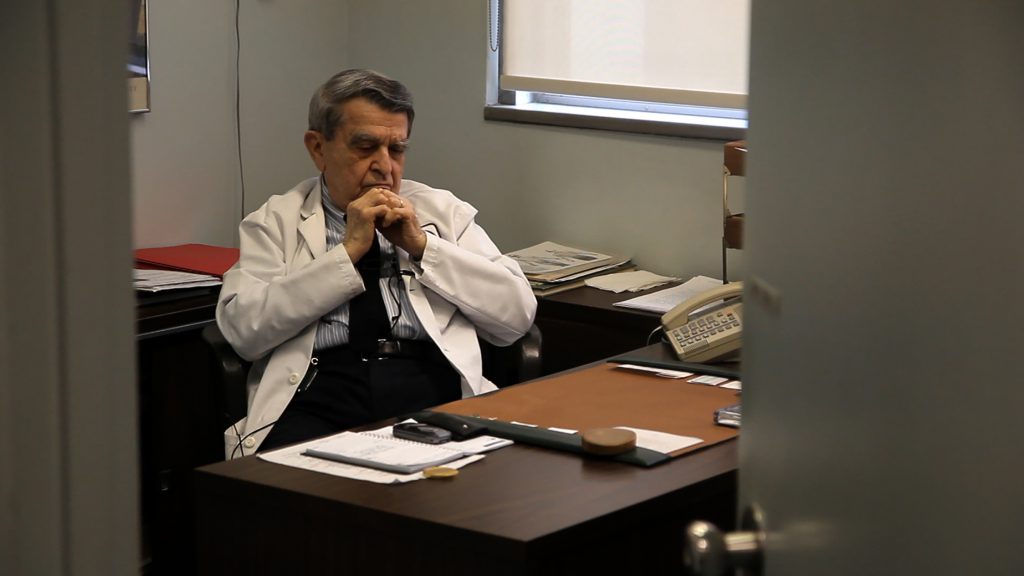

A more recent corollary to this problem is the story of Dr John Sarno, who came to believe that back pain was often a mind body problem which was caused by the repression of emotions rather than structural issues like a “herniated disc”. While Dr. Sarno did not have as much difficulty communicating as Dr. Semmelweis, his profoundly progressive ideas about his field were not embraced in his lifetime. Being pushed to the edges of the medical system was difficult for Dr Sarno, but he found a way to reach patients, as well as a handful of other practitioners, through a series of books that examined the mind body connection.

While he had well documented success in treating patients through both his practice and his books, his ideas were dismissed by those in his field because he didn’t support his work with randomized control trials. Dr Sarno came to question the overriding paradigms of rehabilitation medicine because he found little success treating his patients with the methods that he had been taught to use: bed rest, traction, physical therapy, surgery etc. When he looked at the literature to support these treatments, he could find no compelling evidence that justified any of the practices he had been taught to use. A great fan of Sherlock Holmes, he went to look at his patients’ charts for clues. He found that over 80 percent of them had a history of 2 or more other illnesses that were believed to have a emotional or psychosomatic connection. He spent a couple of years talking with his patients about what was going on in their lives and he came to see that many of them were clearly repressing uncomfortable emotions, thoughts, and feelings. For example, he had one patients who thought his back pain was from his increased weight. It turned out that his weight had shot up because his wife and mother didn’t get along very well, and several nights a week he snuck over to his mother’s house where he ate dinner with her and then went home and had dinner with his wife. His real problem was that he had two overly controlling women in his life and he couldn’t say “no” to either of them.

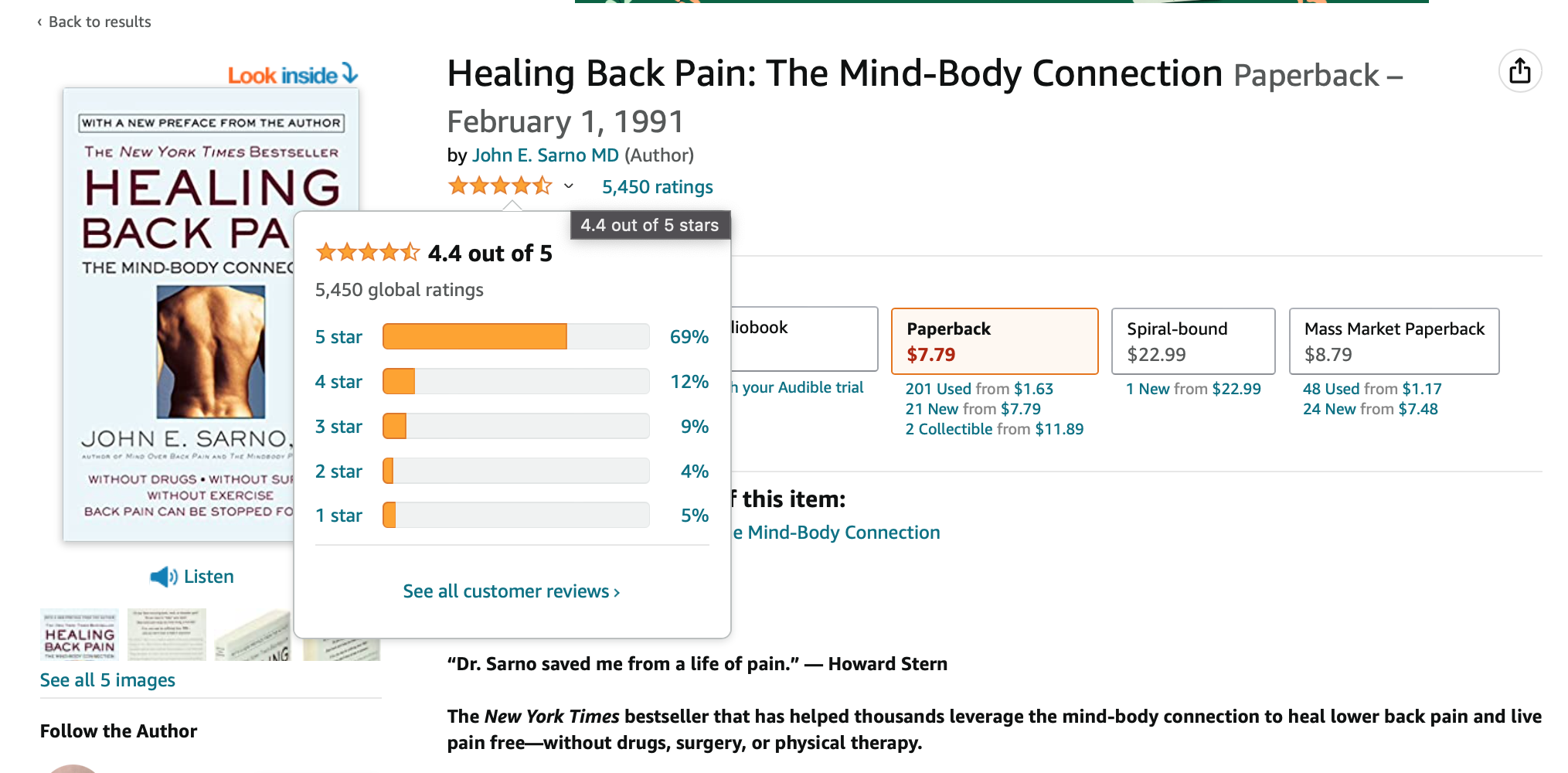

He began to instruct his patients to bring their attention to their emotions rather than the physical pain because he saw these problems as a distraction from, or a manifestation of, more complex emotional issue that they were too afraid to confront, or even see. When he got patients to embrace the emotional underpinning of their pain problem, he found that he had a great deal of success with healing their pain. One of these patients was a book agent who got Sarno a deal for his first book, “Mind Over Back Pain” in 1984. That book and the ones that followed, including the best seller “Healing Back Pain”, reached millions of people. Not every person had a miracle cure from reading the book, but plenty did. If you’re curious, you can search for “Dr Sarno” on twitter where you will find thousands of testimonials. You’ll also find a lot of people calling him a “quack”. While neither these tweets nor the thousands of wildly positive reviews of his books on Amazon (90% positive ratings – 69% 5 star) constitute “scientific data”, it’s hard to argue that he’s a total quack after reading through these thoughtful reviews.

While he had no luck in convincing medical colleagues that the mind body connection was relevant to their work, several people that he helped went on to become doctors and carried on his work. Some of them – including Dr David Schechter, Dr Howard Schubiner, and Alan Gordon – have carried on his work and begun to publish studies based on methods grounded in his work. Dr Schubiner, who recently was involved in a very compelling study that is largely based on his work had this to say about Dr Sarno’s place in history: “Thomas Kuhn wrote about this in The Structure of Scientific Revolution. What he showed through all of these paradigm shifts in science was that ridicule occurs first. Then comes discrepancies in the science…something’s not right, something’s wrong in what we’re doing… and then comes the data. And now we have the data. We know how the brain works. We know that the back’s not broken most of the time. This paradigm is going to shift and Dr. Sarno is going to get the credit that he deserves. And when it shifts, everyone will say, ‘Oh yeah- we knew it all along.’” While Dr Sarno’s name is not yet written in the history books, I believe that he will get the credit he deserves for starting a deeper conversation about the power of mind body medicine.

MIND BODY MEDICINE BEGINS TO ENTER MAINSTREAM AWARENESS

A little over one year ago, on Sept 29, 2021, JAMA published a study authored by Yoni K Asher PhD, Alan Gordon LCSW, and Howard Schubiner,MD, Effect of Pain Reprocessing Therapy vs Placebo and Usual Care for Patients With Chronic Back Pain. Both Gordon and Schubiner, who were mentioned above, were patients of Dr Sarno. After finding healing themselves, they built on Dr. Sarno’s mind body approach and devoted their practice to continuing his work, and building upon it. Alan Gordon published the book “The Way Out” just a few weeks before the study came out and Dr Schubiner’s book “Unlearn Your Pain” came out in 2010. Asher, Gordon, and Schubiner’s study was met with profound interest, yet it also faced a great deal of skepticism. Still, it was one of the most read studies of 2021. A Washington Post piece by Nathaniel Frank, the director of the “What We Know Project” at Cornell University which aggregates scholarly research for the general public, was published on Oct 15, 2021. This article made it clear just how important the study was.

The latest evidence comes in a peer-reviewed study just published in the journal JAMA Psychiatry that includes striking results from a randomized controlled trial conducted at the University of Colorado at Boulder. In the study, 151 subjects with persistent back pain were randomly assigned to one of three groups. A third of them were given no treatment other than their usual care (the control group), a third were given a placebo, and a third were given eight one-hour sessions of a new treatment called “pain reprocessing therapy” (PRT). Developed by Alan Gordon, director of the Pain Psychology Center in Los Angeles, the technique teaches patients to reinterpret pain as a neutral sensation coming from the brain rather than as evidence of a dangerous physical condition. As people come to view their pain as uncomfortable but nonthreatening, their brains rewire the neural pathways that were generating the pain signals, and the pain subsides. […]

This new research is the latest to validate Sarno’s theory that much chronic pain is not structural but is a mind-body phenomenon, and that changing our perceptions — gaining knowledge, altering beliefs, thinking and feeling differently — can dramatically reduce the pain.

This does not mean the pain is imagined or “all in the head.” It’s a brain response, like blushing, crying or elevated heart rate — all bodily reactions to emotional stimuli. “Pain is an opinion,” neuroscientists often say, suggesting not that pain isn’t factually present but that all pain is generated by our brains, and is thus reliant on the brain’s fallible perception of danger.

I’d been waiting for the study to come out for years and hoped that it might move the needle on awareness of Dr. Sarno’s work. I’m a filmmaker, and with my partners Suki Hawley, and David Beilinson, I made a documentary about Dr. Sarno that is also very personal, so I was very excited about the impact this study was having.

THE RESISTANCE

The previous year I had pitched Erik Vance, the editor of the Well Column in The New York Times, about doing an article about Dr Sarno and our film. He had recently taken over the position at Well and had put out a call for pitches on twitter. I sent him a request that he run something about the impact of Dr. Sarno’s work. My note confused him a little; he was unsure about whether or not I was a “writer” pitching a freelance article. I was happy to write one, but I was not really a freelance journalist; I was writing more with a pinch of hope that a new editor might consider recognizing Dr Sarno’s contributions to the field. For some context: the Times had never written about Dr Sarno until they published an obituary the weekend that our film about his work opened. While the film got a decent review in the Times, we were unable to get anyone, in any outlet whatsoever, to write a substantive article about his work. Still, in the years since the film had come out, awareness of the impact of trauma on health had increased dramatically, and that in turn has led to a greater awareness of an evolving understanding of pain that was more in line with Dr Sarno’s thinking. I figured that a new editor might be interested in looking at this shift. I was wrong.

He was deeply skeptical of Dr Sarno’s work and explained that it was “a little late to write about Dr Sarno”. This response was both expected and a little shocking. I pushed back on Vance’s contention that it was too late to give Dr Sarno credit for his work. After several increasingly exasperated responses, the editor explained that he might be interested in covering Dr Sarno’s work if an eminent neurologist like Tor Wager were to do a study of his methods. I was aware that Wager was involved in the previously mentioned study. He was doing FMRI’s of patients brains to see how the mind body treatment impacted them vs placebo, or standard care. So, when the study came out a year after we first talked, I immediately sent it to the editor. I did not get a response. I believe I also sent him Nathaniel Frank’s piece as well when it was published two weeks later.

A few weeks after that “The Well” section ran a multi article series on chronic pain which included a piece written by a science writer who was healed by using Dr. Sarno’s methods. While the author states that she was “cured” by following Dr. Sarno’s recommendations, her piece begins by undermining the validity of the work, revealing the kind of bias against the impact of emotions that has been pervasive in the fields of “science” and “medicine” over the past 70 years,

“Every time someone tells me their back’s been giving them trouble, I lower my voice before launching into my spiel: “I swear I’m not woo-woo, but … ”

“Woo” is a term used to denote “unscientific science”: ideas that have not been sufficiently proven using randomized control trials. One problem with randomized control trials is that, for the most part, the impact of emotions on physical health has been largely ignored as part of these studies for decades. Emotions are messy, individualistic, and seemingly disconnected from classifications of genetics, gender, race, and class, and therefore difficult to account for. So, when studying drugs, surgeries, or other treatments, emotional factors were simply not included in data sets that determine the effectiveness of various treatments. In some sense, this is like being a car mechanic and only focusing on mechanical systems while ignoring the fluid systems. If you pretend that the fluid systems are not important because you can’t quantify how they work, then it’s very likely your car will die much earlier.

After explaining her pain, as well as Dr. Sarno’s basic ideas, DeMelo closes the first section of the article with,

I appreciated the tidy logic of Dr. Sarno’s theory: emotional pain causes physical pain. And I liked the reassurance it gave me that even though my pain didn’t stem from a wonky gait or my sleeping position, it was real. I didn’t like that no one in the medical community seemed to side with Dr. Sarno, or that he had no studies to back up his program.

But I couldn’t deny it worked for me. After exorcising a diary’s worth of negative feelings over four months, I was — in spite of my incredulousness — cured.

Rather than doing further research on Dr Sarno’s work, or how it is connected to a host of other doctors who have made the connection between the repression of emotions and illness, DeMelo centers her own skepticism. By taking an N of 1 approach – wherein the focus is on the author’s experience only, proceeding under the assumption that this experience is not “fully valid” and can’t be considered data because it is anecdotal – the piece undercuts any argument that Dr Sarno’s work was valid. Taking a similar approach, writer Nathaniel Frank, the author of the above mentioned Washington Post Piece about the JAMA study (this piece includes discussion of a separate study by Michael Doninno that sought to confirm Dr Sarno’s work ) also writes from a personal perspective, but has different conclusions. Frank was saved by Dr. Sarno, and uses that understanding to highlight the increasing drumbeat of science that is beginning to emerge that strongly confirms his basic ideas about mind body medicine. The fact that the medical community has completely ignored this work says a lot about the problems of science writing and skepticism.

The Times article is titled “I Have to Believe This Book Cured My Pain”, and the subheading is “A science writer investigates the 30-year-old claims of an iconoclastic doctor who said chronic pain was mostly mental.” It seems somewhat problematic to me that the author is declared to be a science writer, but writes the piece more from the perspective as a skeptical patient rather than as a “science writer”. Unfortunately, DeMelo leans into the skepticism and fails to do any substantive research into Dr. Sarno’s work nor his evolving understanding of pain. DeMelo only mentions that she read Dr. Sarno’s most popular book “Healing Back Pain” which was published in 1991 and written for patients rather than practitioners. In 2006, Dr Sarno published “The Divided Mind”, which included contributions from many other doctors, and focuses much more on the theories that support the work. It makes very little sense that a “science writer” chose to ignore the ways in which Dr Sarno’s ideas evolved as he continued to practice and publish for more than two decades after writing “Healing Back Pain”. It doesn’t help that the editors chose the subheading that they did. DeMelo interviews a few pain experts, but only mentions the 30-year-old book written for a popular audience while failing to research whether or not the work continued to evolve, or how it might be connected to other work that was being done.

What made me most disappointed is that the article goes on to quote two people who were central to the groundbreaking JAMA study that had come out six weeks earlier, yet it fails to mention the study. After the opening discussion of the author’s personal experience of healing using the book, the next section beings with a quote from Dr Tor Wager, whose FMRI’s readings are part of that JAMA study.

“The idea is now mainstream that a substantial proportion of people can be helped by rethinking the causes of their pain,” said Tor Wager, a neuroscience professor at Dartmouth College and the director of its Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience Lab. “But that’s different than the idea that your unresolved relationship with your mother is manifesting as pain.”

Dr Sarno’s theories were rooted in an understanding of Freud. While Dr Wager might be intending to distance himself and his work from Dr Sarno, the article also quotes Dr Schubiner who was a principal investigator in the study,

The bottom line, according to Dr. Howard Schubiner, a protégé of Dr. Sarno, is that “all pain is real, and all pain is generated by the brain.” Today Dr. Schubiner is the director of the Mind Body Medicine Program in Southfield, Mich., and a clinical professor at the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine.

“Whether pain is triggered by stress or physical injury, the brain generates the sensations,” he said. “And — this is a mind-blowing concept — it’s not just reflecting what it feels, it’s deciding whether to turn pain on or off.”

While the article treats Dr Schubiner respectfully, it fails to mention that Wager and Schubiner had been part of a study that delivered powerful confirmation of the import of Dr Sarno’s work. Given my previous back and forth with Mr Vance, I was not surprised, but I was disappointed.

Both the author and the editor are part of the science writing system. In order to be a part of that system, one has to have faith in the rules of that system. Over the past 70 years, the randomized control trial has become the “gold standard” for advancing knowledge. The problem with this system is that, like many other systems, it often becomes stuck in its basic tenets and has trouble recognizing how this can create profound barriers for those who question the basic tenets. Over the past 70 years, people’s emotions have been shunted off to psychology, and any mention of them in regards to “medicine” are dismissed as “woo”.

SYSTEMS AND KNOWLEDGE

For many years I’ve been thinking a lot about how systems simultaneously create pathways to knowledge and profound limits to the expansion of knowledge. To thrive within a system one has to (on some level) both understand and accept the “rules” of that system. Often these rules aren’t entirely clear, but those who do thrive understand them even if they can’t articulate them. I’ve often found myself understanding what’s expected but uncomfortable conforming to those expectations. As I’ve gotten older, and perhaps a little wiser, I’ve stopped caring as much that I don’t fit in them, and that I don’t have the power to change them. Some of this illumination has to do with my work around our film about Dr Sarno, but it’s related to all of the various work I do, including posts like this one. As a filmmaker, I’ve never made films that fit within the expectations of the various film systems, so I’ve always had to figure out how to work outside of those systems to get them seen (we have self distributed all our own work which means that those within the system don’t feel compelled to engage with that work). As a photographer I’ve never made work that has been embraced by the photo system. So, social media has helped me get that various work into the world. I appreciate social media for that reason but also see the perils of it. Without social media the mall work I shot in 1989 would not have been seen, and even with the continued viral nature of it, no gallery has been interested in showing it. It exists in the world but not within that system because it isn’t of that system. Dr Sarno’s work was viral before social media, and it still exists and impacts people but largely outside of the medical system – which also means it exists outside of the media system. So, as filmmakers who aren’t of the film system, who made a film about a doctor who was shunned from the medical system, we made a film that no one in the media system would write about. Systems rely on other systems for confirmation. This leaves a great deal of knowledge stuck outside of general awareness. While Dr Sarno’s work impacts so many, it has largely been left out of the medical conversation, even as it’s a driving force of the change taking place within the system.

THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE IN THE 20th CENTURY

To make sense of what has taken place in the 20th century, it’s important to look back at the the 17th century. At that time, Rene Descartes got into some trouble with the church when he began to discuss consciousness and the brain. In order to keep his own head he agreed to leave the brain to the church and focused his attention in the body. It wasn’t until the late 19th century when Freud presented his ideas of the unconscious that the brain moved back into the realm of science. However by the second half of the 20th century, the bio-technical approach to medicine gained increasing traction, and all discussion of the emotions was squeezed out of the medical realm. This approach was data driven and relied on randomized controlled trials to prove that medicines, and other medical techniques worked better than a placebo (placebo was dismissed as not being a “real effect,” when in fact the placebo represents the power of belief). For the most part, these trials focused on how a physical, chemical, or biological intervention impacted healing. These randomized control trials rarely included data on emotional factors (because the inclusion of emotional factors makes the data less clear), and as this approach to medicine gained more ground, any discussion of emotional impacts, or treatments that involved a focus on the emotions, was pushed to the outskirts of the scientific community.

The result of this history is two-fold: the medical community has no interest in embracing awareness of the mind body connection, and also limited incentives – there is a relatively minuscule amount of funding for medical studies that focus on emotionally-based treatments. It’s hard to get the the same kind of clarity from an emotionally based study as one can from one that simply focuses on how a chemical compound affects people. There’s also very little financial upside for the systems that might “invest” in mind body treatments. The fact is, everyone has different stressors and different reactions to stressors, so everyone will react/respond to different ways. The conundrum we have is that for decades we have pushed discussion of emotions to the edges of our society. It’s not simply a medical reorganization we need, but a cultural one as well.

It was not always like this. In the late 19th century and the early part of the 20th century, Sigmund Freud’s theories of the unconscious led to an increase in the awareness of the impact of emotions on physical health. It wasn’t just Freud though; doctors like Hans Selye wrote papers of the impact of stress on the human body; and there was widespread awareness that our thoughts and the stress we struggled with, impacted our physical bodies. However, after World War 2 the practice of medicine increasingly became focused on finding cures using chemical compounds, surgeries, and physical interventions. There was a belief that if we just figured out what was going on in the body on the cellular and molecular level, we could find the cure for almost any illness. Ideas related to emotions were cordoned off into the fields of psychology and psychiatry. While psychology continued to focus on talk therapy, psychiatry became more focused on finding pharmaceutical interventions than emotional ones. While people continued to see therapists, they were not considered medical doctors like the psychiatrists who proscribed chemicals to cure depression and other “mental illnesses”. To be clear, some of these chemicals had profound effects. Lithium helped people to balance out their bipolar disorders and new drugs helped schizophrenics keep their illness in check. We also saw increasing effectiveness of certain drugs for cancer. This is not an argument that all medical interventions are bad or wicked. Instead, the point being made is that these successes often blinded the system to other ways of approaching the problems.

By the 1970’s medical doctors became increasingly distanced from their patients’ emotional lives, and this pattern continued to grow more profound as the bio-technical approach increasingly diminished awareness of how emotions, and the repression of them, might affect the physical body. This situation was exacerbated by the fact that there was very few, if any, randomized control trials being done that might illuminate the connection between emotional stress/trauma and physical health. Without this data, any discussion of the emotions was deemed “unscientific” and dismissed as “woo”. This is where our first paragraph becomes important. If a system doesn’t have a way to integrate, or explore, ideas that don’t fit within a systems overriding paradigms, then the possibility of incorporating new knowledge gets limited.

THE STORIES WE TELL

Our brains are wired to tell stories, and from the moment we are born we take in stimuli and try to make sense of it through the process of storytelling. First we begin to make sense of our immediate surroundings through touch, smell, taste, hearing, and sight. I would add that I believe that we also have a sixth sense, we sense the energy of the people around us. If our caretakers have a calm energy then we might feel more safe. Early on, those surroundings are literally what’s right I front of us, and for the first few months we are either sleeping or searching for a breast or thumb to comfort us. Our genes, which shape much of who we are, have already wired us to develop in specific ways, and our brain first pushes us to meet our immediate core need for nourishment and comfort. For the few minutes between feedings that we are not sleeping our other senses take in more stimuli and begin the storytelling process. We many not remember these moments in words but they certainly have an effect on the stories that shape us. These stories become the stories that we tell ourselves about ourselves.

We can see the breadth of this problem very clearly when we look at the chronic pain epidemic in America. Since 1985, when America first measured the cost of chronic pain, there has been an exponential spike in both the cost breadth of the problem. Dr Sarno came to see that many “medical” problems, often have a connection to emotional problems, was shunned and ignored for trying to bring attention to this connection. Yet, in the 70’s he predicted the coming epidemic and explained why it would happen. He understood that since the repression of emotions is a major causative factor in many instances of chronic pain his cure involves addressing the emotions directly. He asks patients to recognize the pressures and stresses that they put on themselves to be perfect and good, and make the connection between how this pressure creates a kind of internal unconscious rage at the expectation that they be so perfect. At the same time, trauma from childhood creates fear that these feeling will rise to the surface. So, he suggests that we turn our attention away from the symptom (pain), and redirect it towards accepting our emotions. This post is not meant as a dissertation on his work so I’ll point readers to his many books on the subject, or our film, for more complex explanations. The first line of the film is a personal one. I state in voice over, “The stories that we tell ourselves about about ourselves shape our sense of who we are.” For the last line we hear Dr Sarno state, on his final day in his office, “It all comes down to one simple idea; the mind and body are intimately related. That’s it, that’s the whole story.” The main problem that we faced for much of the 20th century and well into the 21st is that the medical system completely ignored the role of the mind. Like Semmelweis before him, Dr Sarno noticed a problem within the practice of medicine and he set out to figure out the solution by asking questions and trying out ideas.

TRAUMA AWARENESS

Dr Sarno was dismissed because he took a “trauma informed” approach to treating pain syndromes in an era where trauma wasn’t considered or discussed. While it is very quickly becoming normalized to discuss trauma (thanks to people like Bessel Van Der Kolk and Dr Gabor Mate) he developed his ideas 50 years ago when it was not. In short, he came to see that the origin of the back pain that so many of his patients suffered with had its roots in emotions that were being repressed due to childhood trauma, and that this was causing their pain. While this ideas is hard for many people to believe, when his patients worked to connect with those emotions they often had profound and long lasting relief from pain. As someone who has a long family history with him and his work (40 years), it made a lot of sense for me to become part of the story. In the end, his agreement to work with us to help tell his story put an incredible amount of responsibility on my shoulders to not give up on telling his story. It also means that in some ways I have a responsibility to not allow his contribution to get lost in the current rush of interest in trauma informed approaches to healing.

The good news is, when I can get the film in front of people, it has a tremendous impact. Every week I get notes from people letting me know that the film has changed their lives. At the same time, despite all of the resources I have put into getting the film seen and written about, there has not been a single article written about the film or Dr Sarno. That’s not entirely true; Dr Sarno passed away the day before the film opened on what would have been his 94th birthday. Given that the film had opened that week, The NY Times ran an obituary about him on the Sunday of that first weekend of screenings. A couple of years later the website Vox ran a long article about back pain, and they failed to mention Dr Sarno. The author explained that she had heard about Dr Sarno, but “didn’t buy” his ideas. Still, she ran a largely skeptical follow up article with the headline, “America’s most famous back pain doctor said pain is in your head. Thousands think he’s right.” I begged the author to correct the headline because it was factually wrong. He never said that pain is all in your head, and this insinuation is damaging. She refused to change it, “We don’t agree with your interpretation of the headline, however, and the story is quite clear about his ideas, so we think it’s fine to leave.” This is the only piece that was written, and it started off with a profound bias against him. While an inflammatory title gets more clicks, it also further amplifies the kind of inaccurate narrative that leads to greater resistance to the simple idea that the mind and the body are intimately linked.

Dr Sarno did a great deal of work to illuminate these very simple ideas. As a filmmaker involved with telling Dr Sarno’s story, I’ll continue to make the point that, like Semmelweis, he deserves much more credit than he’s received.

No Comments