06 Mar Unconsciously Photographing Consciously.

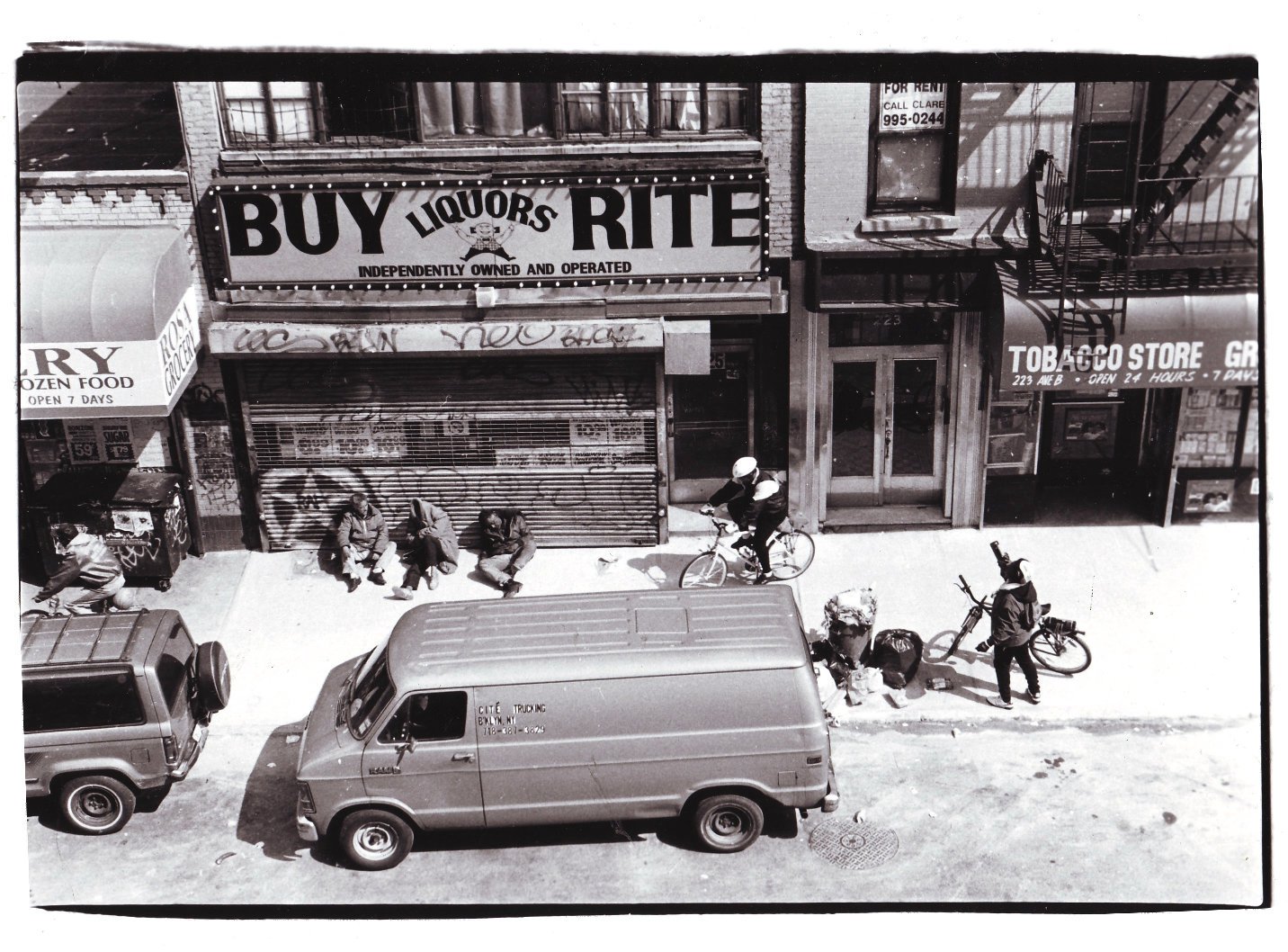

a shot out of the window of 224 Ave B- the building I moved into that was heavily featured in Ken Schles’ “Invisible City”

One of the major rules of filmaking is “show, don’t tell”. We are visual people by nature and when we hear facts they stick on one level, but they don’t affect us as emotionally as images. If you tell me, “10 people died” it goes to one place in my brain. If you show me 10 dead people, it goes to another, and I think we can all agree that it has a powerful impact. These images affect us in very conscious ways.

In the same vein, we learn much more from example than we do from command. That is, if I yell at my children not to yell at each other, it will be a lot less effective message than calmly telling them not to yell at each other. I’ve been thinking a lot about this idea in relation to art; why I make it, and what it means. A couple of days ago a friend and fellow photographer stopped by and I showed him two books that had a profound effect on me as a photographer. Until recently I was only aware of the impact of one of them.

I have long known that Ken Schles’ “Invisible City” had a strong influence on my style (especially in the layout of my early books) but until last summer I hadn’t realized the powerful influence that Helen Levitt’s “A Way of Seeing” had on me. In July, while helping my mom go through the things in her house, I came upon this book and I flipped through it. I had visceral memories of lying on the living room floor as a child repeatedly doing the same. The images in the book jumped out at me as familiar, yet I only vaguely recognized them. It was clear that to me that my earliest understanding of photography was formed by this book, in addition to looking through another of my parent’s books, Avedon’s collaboration with Truman Capote, “Observations”. Both books incorporate words and images, and both photographers attempt to capture the ineffable human spirit.

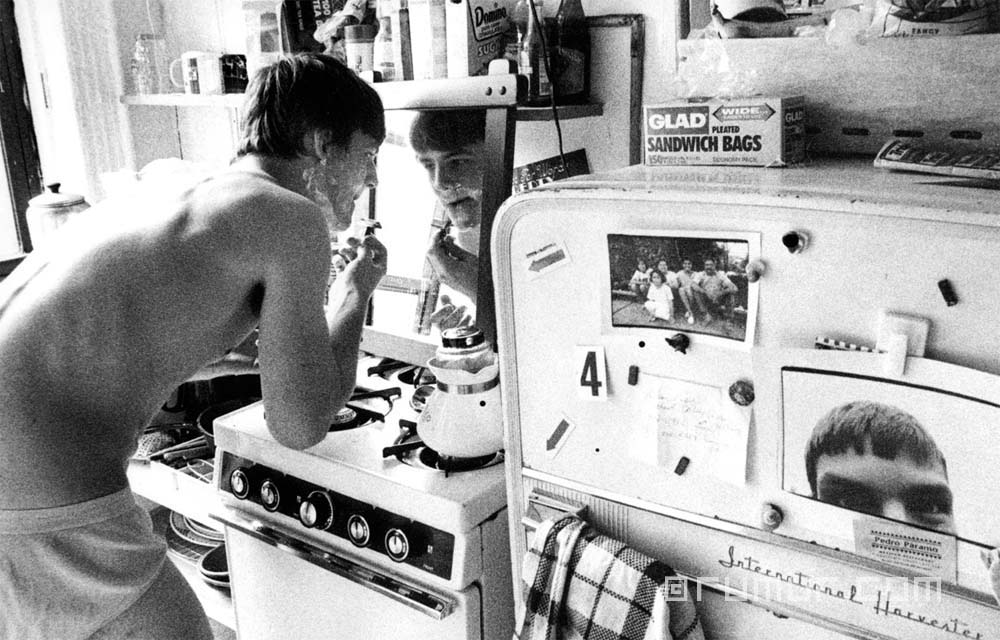

As I showed my friend the Levitt book I realized what a profound effect it had had on me. In fact I saw one image that made me pull out my phone to show him one I had taken only days earlier.

The framing of both was connected. Both my image and hers were not planned, they were grabbed, and I knew immediately upon seeing hers, that the “idea” of this image was present when I shot mine. I recall seeing something in the composition of the father, the door frame, and the mother and child that made me lift my phone and snap the image. Something felt familiar and I wanted to capture it.

I imagine I might have still been interested in photography without having had these books lying around my house. However, having these books around certainly shaped my thinking about what a photograph was. As I was talking to him I recalled a study that showed that children who grew up with more books in their houses had better educational outcomes. They didn’t have to read books, they simply had to have them in their house. On one level it would be easy to make the correlation that people with more means and education have more books and therefore it’s simply a class issue. However, I also think that when we have books around we value them, and that value leads to more complex thinking, more imagination, the ideas help within create a framework for learning. No one in my family showed me the Helen Levitt book and said look at this (though they did take us to some museums and did encourage us/ force us to read). However, simply having that book in the house unconsciously shaped the way that I thought about photography. “This is what photographs are,” I came to believe. Subsequently I was drawn to work that built on the legacy that Helen Levitt herself had built upon.

I’ve told this story before, but when I first saw “Invisible City” for sale on the street I was drawn to it. It cost a lot more than other books I bought on the street and I tried to walk away from it but I could not. I had to have it. It spoke to me so strongly because it achieved something that I had been reaching for, and I now realize it spoke to me as an extension of “A Way of Seeing”, and even as an extension of “Observations”. At the time I was working on a project about the street vendors of Astor Place. It’s only now that I realize how much Levitt’s book created an unconscious frame by which I thought about photography. Frankly, if anyone had asked me about it, I might not have even recalled it, but I know now how profoundly it affected me.

In some ways, the same is true of “Invisible City”. I flipped through it a few times after I took it home, but I did not study it. In fact I did not even notice the photographer’s name. A few years later, when I had unknowingly moved into the building that much of that book was shot in, a friend asked me if I knew Ken who lived in the building. She did makeup work on his commercial shoots and thought I would like his photo work. I immediately knew that he must be the one who made the book I loved. However, it was lost and it took me a couple of months to track it down. When I opened it up I realized its connection to my home. For me, the images in “Invisible City” created an unconscious frame that defined a romantic bohemian vision, and I had somehow unconsciously willed myself into that space.

When I look back at how I laid out my first books, especially my book “Lost” which remains unpublished, I realize that the influence is perhaps too strong for comfort. I had not consciously tried to ape the style of that book, but it had unconsciously shaped my idea of what a book was. Ken recently referred to “Invisible City” as something of a “chapter” in the life of the East Village. In some ways my book is perhaps the next chapter of that book.

Such is the power of images that it would have been difficult for me to photograph that time and place in a wildly different manner, because in some manner I was living my life based on those photos. I was an actor in a romantic noir film that at times turned comedic. My work has gone through different phases since then, with each change building on the next, and in some way related to where I am in life. Now I photograph my children a lot, and as they are wild and colorful, so is my work. I play music with them, I ignore them too much, and I work too hard. I take solace in the fact that like I took as much from what my parents provided as what they said, that I too am providing a lot for them.

No Comments