05 Mar Whole Person Medicine

Humans have a tendency to want to think of ideas, as well as scientific “facts”, as solid and immutable. Unfortunately, things tend to be a lot more complex and nuanced than we want them to be. This is nowhere more evident than in health care. The disease model of medicine looks for a single cause of illness because that makes it explicable as well as seemingly more possible – and more profitable – to treat. However illness can very rarely be found to have a simple single cause, so the drug therapies that we focus on developing for complex illnesses rarely affect people in the same way. While illnesses like the common cold, or staph infections can be clearly linked to a pathogen, scientific studies have shown that people who are dealing with simple life stresses are both more likely to get sick, and take longer to get well. This information doesn’t negate the fact that a pathogen is involved in the illness, but it does point out that we shouldn’t focus only on the obvious physical causes when we approach the process of healing. In general, the medical system as it exists now does a terrible job of integrating awareness of how our emotions, stress, and environment affect our health.

The tendency that we have to ignore information that challenges our core beliefs can lead to a great deal of suffering. Trying to figure out exactly how the mind-body interaction plays a role in illness is a daunting task, especially because it is clear from all the data that the interaction is complex. Viewing health through a complex lens – in which health outcomes depend on an individual’s genes, life experiences, environment, diet, and life choices – makes designing a study that can “prove the link” between the kinds of stress we face and our health outcomes nearly impossible. When we add in the reality that the entire medical system is geared in the opposite direction, avoiding discussion of the stresses that it cannot control and has no way to “treat”, the difficulty of integrating mind-body awareness into treatment methodologies begins to seem insurmountable. Further, the fact that most doctors are completely averse to talking about emotions, and in fact have often been taught to “not open a pot that they can’t stir“, it’s hard to see the light at the end of the tunnel. However, having worked on our film about these issues for 10 years, I can say with great confidence that we are in the midst of a massive cultural shift in terms of our acceptance of the import of our emotions in relation to health. Just as most people have trouble believing in global warming because they haven’t been watching the ice melt, most people are not as hyper-aware of how much our culture is shifting as the people with a google alert for “chronic pain”. We have tracked this story as it has moved through the world over the past 10 years, and the shift is now exponentially faster.

When we first began making the “All The Rage,” simply suggesting the idea that we should pay attention to the mind-body interaction in terms of our understanding of illness was challenging, to say the least. When we tried to explain Dr. Sarno’s work, which focuses on the idea that the repression of our emotions is a primary cause of the pain epidemic, we were often met with confusion and anger. However in the last few years, what started as a slow drip of information about research that made the connection between stress and illness has become a deluge of studies, articles, magazines, and even films. This week, there have been two major stories on NPR’s “All Things Considered” that deal directly with this issue.

Yesterday I wrote about how we have been struggling to come up with the opening of the film because it will set both the intellectual and aesthetic tone for everything that follows. Even two weeks ago, I think I would have balked at the idea of including anyone who raised the idea that the story is about more than just pain. However, just 10 minutes ago, we were discussing putting in a quote from Howard Stern wondering what would happen if other doctors would simply listen to what Dr. Sarno has to say. “If mainstream medicine did understand Dr. Sarno’s theories, there’d be a revolution. It would open up research. Who knows what the brain is capable of doing by controlling a couple of blood vessels in our body. This pain that we experience is just from a slight squeezing, a restriction of an area. Can you imagine what else the brain controls in our body that we consider incurable. We might be talking about the motherlode. We might be talking about cancer. We might be talking about all kinds of other things… but you can’t move the world along too fast.”

Last week I would have worried that people hearing that line would think that we were revolutionary nutcases, with little grasp on reality. We have been counseled by many doctors to stick to the science, lest we lose the doctors in audience who need to hear this message. However, after hearing the last two days of NPR stories which focus on the powerfully negative effect of major stress in childhood, we came to realize that by the time the film is done, this idea will be accepted by the vast majority of people. People are simply becoming aware of this idea in droves, which means that people are ready for this film. I don’t even think that doctors will find the ideas challenging by this time next year. We are in the midst of a major cultural shift.

On Monday March 2, there was a story about how Adverse Childhood Events affect health. In the late 80’s, Dr. Vince Felitti, who was treating patients struggling with obesity, noticed a connection between extreme stress in childhood and their weight problem. In talking to them, he realized that a startling number had been sexually abused as children. He started to ask more patients about possible trauma in their childhood and found that many of them had what he called Adverse Childhood Events (ACE). You can take the ACE test at NPR. The adverse events they looked for included things like verbal and sexual abuse, mental illness in the household, drug and alcohol problems in the home, and a death or a divorce in the immediate family. The more he looked into the connection between these kinds of major childhood stresses and illness, the more profound the connection seemed to be.

In the early 90’s, Felitti got together with epidemiologist Dr. Rob Anda, and they ran a large survey of 17,000 patients. They published their findings in 1997, detailing a powerful connection between ACEs and illness. What they found was startling.

Even though Felitti and Anda were just getting a rough measure of the severity of the patients’ experiences, when Anda’s team at the CDC crunched the numbers, he was shocked.

One in 10 of the patients surveyed had grown up with domestic violence. Two in 10 had been sexually abused. Three in 10 had been physically abused.

“Just the sheer scale of the suffering — it was really disturbing to me,” Anda remembers. “I actually … I remember being in my study and I wept.”

And then came the part where he found out what happened to all those people when they grew up: “very dramatic increases in pretty much every one of the major public health problems that we’d included in the study,” he says.

Cancer, addiction, diabetes and stroke (just to name a few) occurred more often among people with high ACE scores.

Now, not everyone who’d had a rough childhood developed a serious illness, of course.

But, according to the findings, adults who had four or more “yeses” to the ACE questions were, in general, twice as likely to have heart disease, compared to people whose ACE score was zero. Women with five or more “yeses” were at least four times as likely to have depression as those with no ACE points.

They expected the medical community to respond to the report with excitement, but instead found that they couldn’t get many doctors to pay any attention at all. Nadine Burke Harris speaks eloquently about this issue in a TED Talk posted below. She came upon the study well after it was released, only after she started to look for evidence of what she had observed in her own practice. When she found it in the ACE study, she too assumed that medical practice would change both rapidly and radically, in an effort to implement changes based on these important findings. Like the creators of the study she was also disappointed to find that people didn’t seem to want to hear about it.

It’s difficult to turn around a moving ship, but in order to do so, one has to get the captain to realize that it’s time to turn the wheel. Despite the powerful information, and data they possessed, these doctors had a hard time convincing their community that they knew the correct course to take. One problem they faced is that while they were able to detail a powerful correlation between ACE’s and illness, correlation does not prove causation. While there is clearly a connection between the two issues, most doctors resist a change in course unless there is “proof” that this connection entails the possibility of a clear treatment plan. Some doctors are skeptical, and correctly point out that while there may well be a connection between illness and childhood trauma, not everyone who had trauma gets ill. However, while there were not many follow up studies to the ACE report, Dr. Falletti did track 100,000 patients at the hospital he worked at in the year after they were quizzed on their childhood experience. What he found was that over the course of the following year, these patients returned to the doctor 35% less often. The study did not answer the question of why they didn’t come back, but the potential cost savings in both dollars and health is enormous. Skeptics still argue though that there is no proof that asking these questions will lead to better health.

I believe this is a straw argument. There is no evidence that asking people about the stresses in their childhood and their lives could lead to negative results, yet there appears to a great deal of evidence that integrating an awareness of these issues into treatment can yield profound benefits.

Dr. Sarno faced similar skepticism when he started to tell people about the realization that emotional repression had more to do with pain than the physical diagnosis most of them had been given. After practicing with an acknowledgement and awareness of emotional factors for several years, he began to see a profound improvement in his ability to help patients heal. He tried to share his findings with his colleagues at NYU, but they thought of his work as profoundly unscientific because it wasn’t based on randomized controlled trials – the gold standard for scientific research. These doctors wanted to see results of studies, but Dr. Sarno was focused on his practice rather than research.

He based his conclusions on a combination of his medical training and the observation of his patients in his practice. He was inspired to question the standard care that he had been taught – things like bed rest, physical therapy, as well as heating and icing – when he found that these treatment modalities did not work for his patients. He then looked for the research that supported standard care and he found that there wasn’t any compelling evidence for any of it. He then looked at his patients’ charts and spotted patterns. He noticed that the vast majority of his patients had a history of two or more health issues that were believed to have a mind body connection; things like migraines, colitis, eczema, and ulcers. Realizing that there might be a connection, he began to question his patients about their current lives and their childhood. He quickly noticed that most of his patients had a tendency to be perfectionists and people-pleasers who tended to put great pressure on themselves. When he got them to see how they might be repressing their feelings unconsciously and that it was likely connected to their pain, he found that many of them improved rapidly. He came to understand that learned reactions to stress as well as the repression of emotions – all behaviors that his patients had learned early in childhood – were far more powerful in relation to their pain than any physical indication he could find. His prescription was astoundingly simple. He found that if he helped his patients make the connection between the repression of their emotions and their pain, the pain would go away. For some the result was immediate. For others it took more time to fully heal. Others needed therapy to help them get past their problems. He found that far more patients got better from this knowledge than they did from physical therapy, bed rest or surgery.

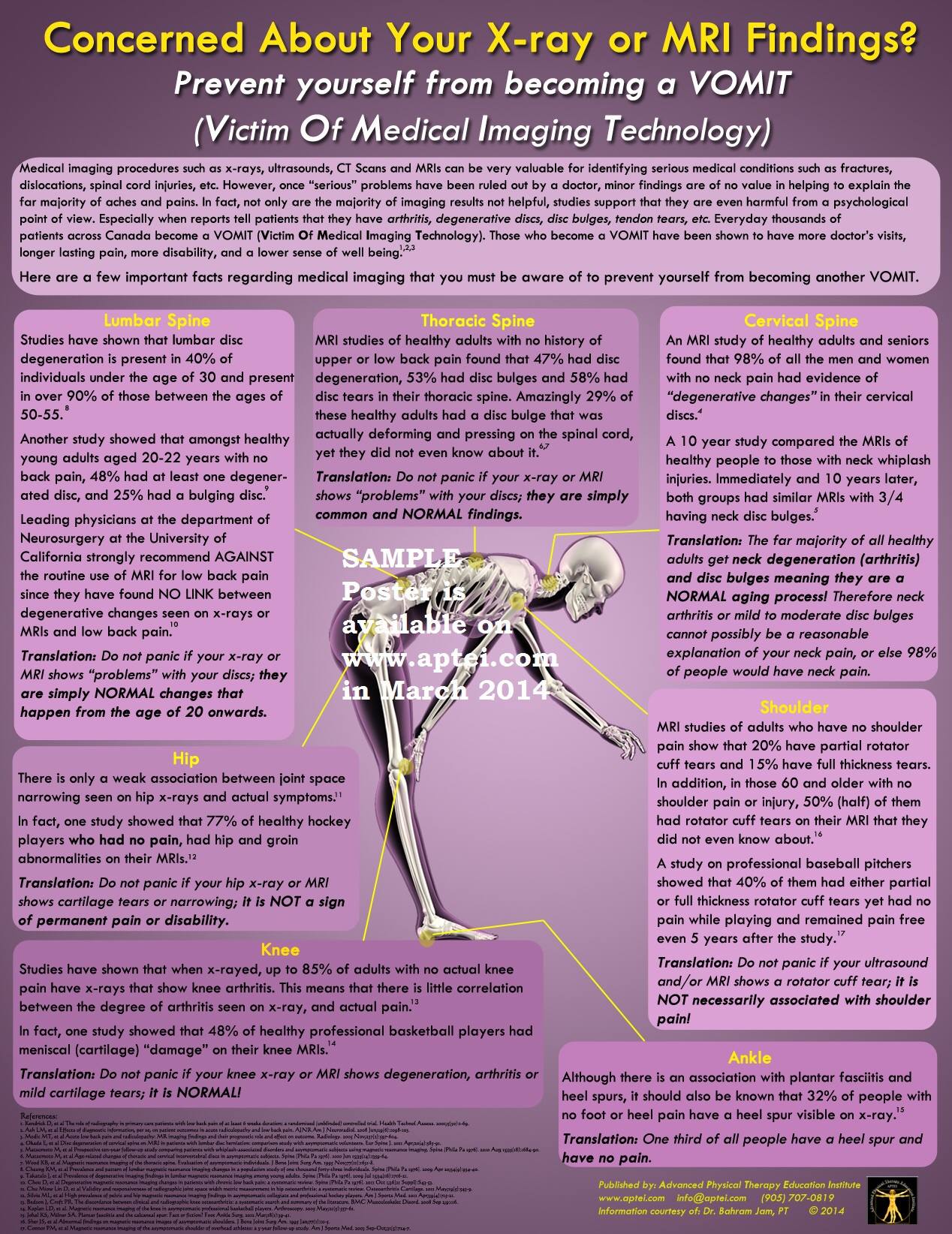

Dr. Sarno’s practice did not focus on research, but through careful observation of his patients, their behavior, and their life histories, he was able to develop a treatment protocol that led to startlingly positive outcomes for many of his patients who had suffered from chronic pain for years. While his methods were being dismissed as unscientific, he bristled at the idea that what he did was less scientific than his colleagues. He was particularly frustrated by the way in which doctors accepted the idea that herniated discs were the cause of pain. When he examined patients, he often found that the disc that was supposed to be responsible for pain did not match up with the area where the pain occurred. He also pointed out that many patients had terrible looking discs and no pain, while others had no disc herniation and severe pain. He argued that the billions of dollars spent on disc surgeries result in a massive placebo affect. Science has proven him correct. When he made these claims, there were no studies to back up what he said. Now countless studies exist in which technicians are given MRIs to analyze from 100’s of people, and the technician is unable to identify those people who have pain and those who do not. Not one study has proved the connection between herniated discs and pain, yet surgeons continue to routinely operate on these discs.

While the ACE study was initially met with little fanfare, interest in the mind body connection has grown rapidly. It’s hard to imagine this story running on the radio 5 years ago, but cultural awareness of this issue has risen drastically over the last year. In fact, NPR decided to run a series of reports on this connection which is a further indication that the public is ready for the import of these ideas.

The idea that childhood abuse and neglect could affect adult health was a revelation to Felitti. But a poll released Monday (from NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health) finds that the public widely believes this to be the case today.

Using Dr. Sarno’s method, the treatment is simple and clear. Patients are instructed to think emotionally rather than physically, they are encouraged to resume all physical activity as soon as they are able, they are encouraged to journal each day, and instructed to read Dr. Sarno’s book. In the past, he had patients come to a lecture and provided small group meetings as well. His prescription is knowledge. A lot can be taken from this simple and open course of action, and applied to the larger health care industry. A few months ago, before I knew about the ACE study, I started to write a post about a study that I wanted to design in which some patients were informed that “we have started to learn from science that our emotions play a major role in our health, and increasing awareness of that fact leads to much better health outcomes. Given that information, I’d like to ask you to think for a moment about all of the things that are going on in your life, family stresses, work stresses, and other fears that might be contributing to the illness that has brought you here.” Others would not be given this question. I think that we would find that health outcomes would dramatically improve for those who were treated as humans rather than a cluster of symptoms.

Drs. Anda, Feletti, and Burke have all expressed a sense of frustration that their colleagues have not embraced these ideas with gusto. Again, one of the issues that other practitioners raise is that knowledge of the connection does not mean that there is a simple solution to the problem. This is true. However, those who do nothing in the face of awareness are often on the wrong side of history. When I look at the problem, I see vast value in simple awareness. Many of the adverse events described in the ACE study are clearly the result of learned responses to stress that are passed down to children. When a parent yells at a child or hits a child, or abuses drugs, that child is much more likely to do the same thing in their life. Through awareness, we can break these cycles. My father, who was a wonderful man, had a tendency to fly into rages over small things. Despite my efforts not to repeat his mistakes, I often lose my temper with my kids. Armed with the cold hard facts that this behavior is damaging to my children, not just in the moment, but in the long term, I have more will power to break these patterns. I also have even more impetus to deal directly with my failings in the short term, working with my kids to mitigate any damage by addressing my failings as soon as possible. For every parent who is given the opportunity to deal with their emotions in relation to their health, a child is given a head start on dealing with theirs. The reality of this issue is borne out by a conversation between Dr Felitti and a patient that’s featured in the NPR piece.

It took about a half hour to go over everything — which included some issues with irregular heartbeat, weight gain, allergies and an eye problem, in addition to the questions about Ratliff’s childhood. It took a bit longer than a typical doctor’s appointment, but otherwise wasn’t so different. Despite the intimate content of the conversation, Ratliffe, [the patient] never got upset.

“You don’t feel like you have to bare your emotions, you know?” Ratliff said afterward. “If it’s just, like, just a checklist, and you can just check off these things that have happened to you — ‘yep, yep, yep’ — it doesn’t feel so scary.”

Felitti hadn’t even mentioned the term “ACE score,” or told Ratliff what her score was — 4 out of 10 — but he methodically had asked her how she thought each adverse childhood experience had affected her. After the appointment, Ratliff said that as she spoke with Felitti, something clicked into place.

“I’ve done a lot of thinking about how my childhood experiences have turned me into the person I am, how I still carry them with me,” she said. “I haven’t necessarily connected it, for the most part, to physical issues before this.”

That’s the point, Felitti believes: Asking patients about ACEs helps patients understand their health more deeply, and helps doctors understand how to help.

While standard care still does not include the value of looking at the whole person, the evidence is increasingly clear; when we focus on specific symptoms rather than the whole system, we are severely hampered in our ability to help people heal. A number of pioneers – Drs. Felitti and Anda, Dr. Gabor Mate, Dr. Andrew Weil, Dr. Sarno, and Dr. David Clarke, many of whom are looking to a past that we have forgotten – have begun to pave the way for a revolution in health care. It is our hope that “All The Rage” will become a vehicle that will allow them to deliver their message of whole person healing.

No Comments