18 Oct Divided

This morning I woke up early because I needed to help my daughter study for a test that she was feeling extreme anxiety about. The anxiety was so intense that we didn’t talk about the test at all, but instead I tried to help her process, and let go of, the anxiety. We made a little bit of progress and as she took off to jump in the shower I got a Facebook alert telling me that a court solidarity event I had been invited to was taking place in a hour. I hadn’t been sure that I was going to go, but I felt like I needed to in order to complete a film we are working on about the Silent Sam statue protests at UNC.

Over the past year, we have documented a number of conflicts related to Silent Sam. We fell into this project, after having completed a film called “Working In Protest” which was woven together from 30 years of our own work documenting protest (The film plays locally at the Carrboro Film Festival on Nov 17). For the most part, the pieces that make up that film are observational, and don’t focus on characters as much as they observe events like a Klan march and protests like those at political conventions, rallies, and the Inauguration. We didn’t set out to make a film about protest, but once we realized we had a good chunk of it done, we shot the last section with a more direct sense of purpose. Then in the fall of 2017, after having completed “Working In Protest”, we shot a couple of short films documenting large protests about confederate statues in Durham and Chapel Hill that took place right after the chaos in Charlottesville. We saw there might be a documentary to make about the Silent Sam statue in Chapel Hill because it was a very heated subject. I went back a couple of times to shoot, but ultimately I felt that the kind of film that needed to be made was one that should be made by the community fighting to get rid of the statue. A teacher at UNC got in touch with me and told me her students were making one, so I gave her all of my footage to share with them and I let that project go.

My wife and I have been making films together for 25 years (with our partner David for the past 20). She went to film school and I took a lot of religious studies and sociology classes while focusing on photography. The combination of our interests and skill sets have helped us to forge a constructive partnership. While we have largely made character-driven films, we have recently been struggling with how to document protest. Focusing on characters is important for storytelling, however, while shooting at the leaderless protest movement known as Occupy Wall Street in 2011, we worked on developing a method of documenting in which the protest itself becomes the main character of the film.

We were first drawn to Occupy due to activist work that was being made about it. However – while I found the advocacy work to be compelling – I also saw it as somewhat problematic: it felt a bit too much like propaganda. For those who already aligned with the ideas embedded in the advocacy work, these films could be very exciting and, on some level, empowering. However, I was also aware that for anyone who held contrary beliefs, that kind of advocacy would be immediately rejected. In fact, advocacy work has a tendency to drive division rather than broaden unity. I think we can see that playing out in profound ways culturally right now.

In the 25 years that we have been making films, my understanding of the relationship between subject and filmmaker has gone through some large shifts and arcs. When my partner Suki and I made our first narrative film “Half-Cocked,” we made it as a fiction film largely because we felt like we were so much a part of the community we were focusing on that we didn’t have the “critical distance” necessary for a documentary. In other words, I had so internalized ideas related to sociology and anthropology that I didn’t see how one could make a documentary without a colonial perspective. At the time, there was a sense that if one related too much with their subject, then they didn’t have enough “distance” from the story to accurately observe and report on the situation. One had to be outside of it, it was thought, in order to see the “truth” of the story. On some level that makes sense, because if we get too close to people in the story there can be tendency to “go easy” on them – to not show all of their horns and their halos (our third film was a documentary called “Horns and Halos“). Years later, I started to question that idea and began to see it as deeply steeped in colonial thinking.

In 2011, a friend asked me to come to Iraq to make a film about his students who were going to perform a Shakespeare play. I told him that I wouldn’t do it, but that instead I would work with them to help them figure out how to make the film. It wasn’t just that it was a Shakespeare play which made the connection to colonialism so much more present, it was that my thinking on documentary had shifted to the point that I wanted to do what I could to help others tell their own story. At the time, we were also working on a film called “Who Took Johnny” which was the story of a mother’s 30-year search for her son who had been abducted. He was the first kid on a milk carton and his mother had been relentless in her advocacy on his behalf. At the same time, she had been portrayed in the media as a bit of a looney bird, and while the story was very well-known, no one had ever done a comprehensive piece on it. We decided to tell the story from her point of view. Rather than approach it as “journalists” getting to the bottom of the “facts” as so many news shows had done, we wanted to create a space for her to give her perspective.

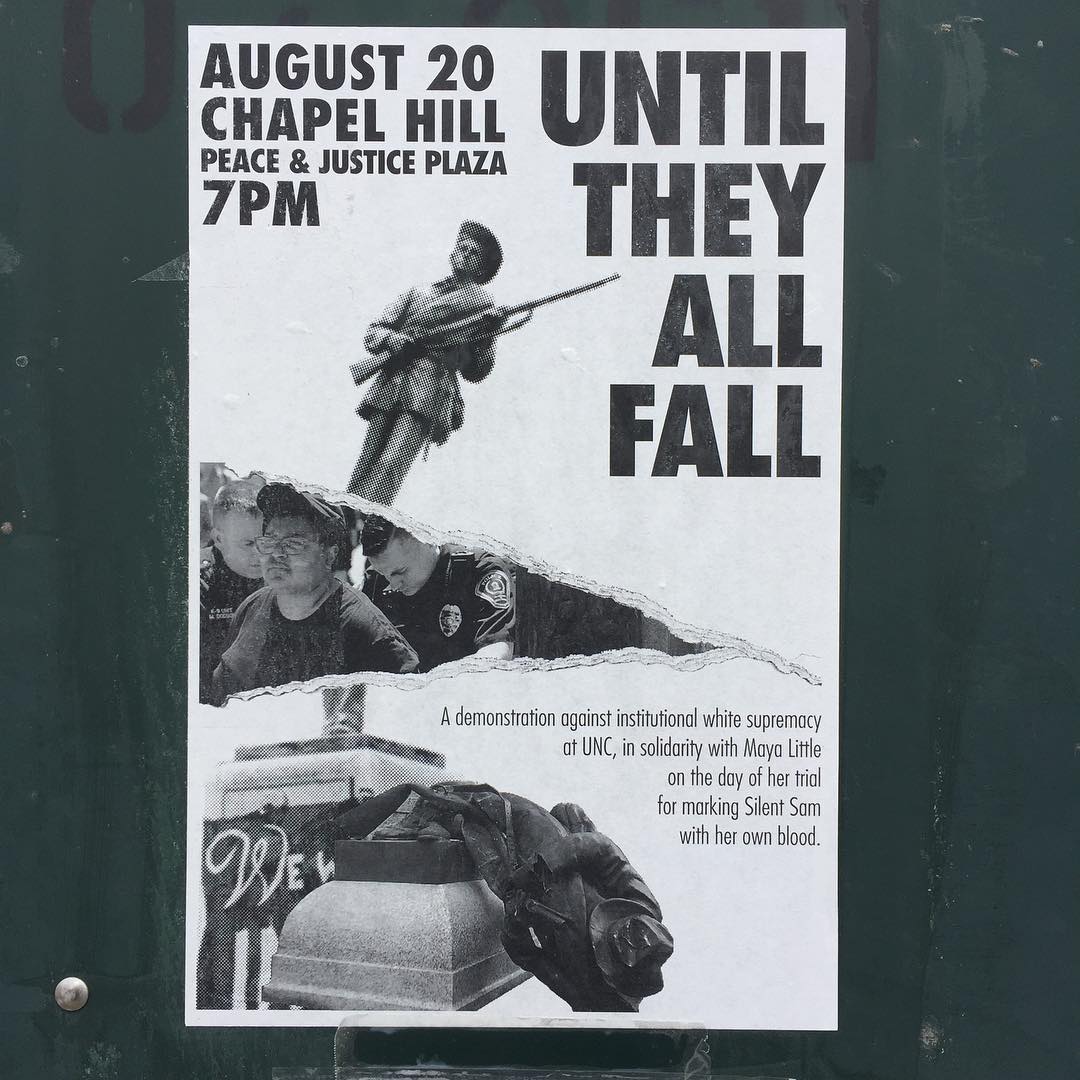

A couple of months ago, I saw a poster announcing another protest against Silent Sam to start the school year. In some sense, “Working in Protest” had come together because I began to shoot more local events in order to bang out quick video pieces about them so that the community would know what was going on. The same was true of the other short films I had made about the statues. I shot them and stayed up all night editing so they could be seen the next day. I set out to do the same this year. As soon as I got there, I had a sense that things were even more organized, and that the police had given in. There were no barricades around the statue and as the protesters marched upon it. they lit a smoke bomb. In the chaos that followed, the protesters were able to wrap the statue in large banners. It was clear that it would be coming down. A couple of hours later, protesters dragged it off its pedestal.

I rushed home and got up a short film by the following morning. When I awoke it had been viewed thousands of times. Interestingly, those who wanted Silent Sam down championed the short- as did those who wanted it up. In some sense, that means the work had been even-handed enough for divided nations to see it as their own. There was a small confederate rally the following Saturday which I didn’t get to film as I was on another shoot out of town. A few days later there was a much larger one that got quite heated. Several protesters were injured by police who also used pepper spray to disperse the crowd. The following week, there was yet another Confederate rally that also got very violent. We cut short films about both of these events and we began to see that perhaps we had another long film to make by tying these works together.

Earlier there was a trial of one of the protesters who had poured blood on the statue last year. I didn’t hear about it until after it happened so I missed it. It felt like we needed something like that to close the film, so when I got the reminder that there was another trial today, of a group of the protesters who had pulled down the statue, I felt like I had to go to film it. When I got there, I filmed a shot of the courthouse and then I turned and filmed a group of protesters. Two women came over and told me that they didn’t consent to be filmed. One aspect of a free media is that people in a public space don’t have a right to privacy. They can’t legally deny anyone the right to film them. However, I had no interest in conflict so I simply said “that’s fine.” and put down my camera. I wavered on whether or not to go and film the trial at that point. I simply had a bad feeling about the situation.

A few minutes later, one of the protesters began to stalk me, standing a few feet away and looking away from me. A few minutes later he walked away and surreptitiously took my photo. I approached him and introduced myself, explaining that if he was nervous about who I was he could simply ask me. I told him that I had filmed a number of pieces about the events including many that had been widely shared. I also told him that I had been in communication with the people behind the “Move Silent Sam” Facebook page, but that they had declined to give me their name. At that point, another protester came up and said, “is there a problem here?” Again I told them who I was and that I had simply been shooting establishing shots of the courthouse and the group.

This guy then told me that I should be shooting the cops and not the protesters. I pulled out my camera and showed him the two shots I had made, one of a cop going in the courthouse and a wide shot of the protesters under the trees. I explained that in order to tell a story, one needs to create the setting. I wanted to say that I don’t tell the protestors how to protest, so I’m not sure why he thought it reasonable to tell me what to shoot. The truth is, I am very much in agreement with the protesters. However, I don’t think it is useful to make propaganda. In fact, a culture that relies almost entirely on propaganda to spread ideas is a culture that is going to be constantly in conflict. The protesters told me that trust takes time. I understand that, but I wasn’t asking for them to open their souls, nor even say anything to me. The two previous trial solidarity events had included tables of food that were gathering places. I had assumed that this would be no different. However when there was no table or central gathering place I had decided to keep a distance and just shoot the couple of establishing shots before going in. I understand the need to build trust if one is going to create a character driven piece, or make a film from a very particular perspective. For me this was more of an experiment in regards to making work that is neither colonial, nor personal, nor journalistic (who, what, why, when, where), but instead just kind of floating in an observational space. I thought about how we might give the piece more context but in the end, we realized that we wanted to capture the situation at the edges and from within the events. I went to the jail event because I thought I might find a way to bring closure to the piece. However, after being stalked I realized that I already had the ending.

A couple of weeks ago, there was a protest in which students declared that they wanted support from the university rather than opposition. At the end, they recited a poem by Assata Shakur. I think that this is how we will end the film. There will be no finality to this story. It is open-ended like all stories really are.

UPDATE- Action around the statue continued to unfold and we shot several more scenes – including the removal of the base of the statue which gives the film more of a sense of finality. When we showed the film at the True False Film Festival in Missouri, one of the filmmakers who worked on the film that we gave our footage to led a direct action protest against us and our film by taking over the q and a at our final screening. They read a statement denouncing us and our work. After that we decided to pull the film from upcoming festivals in order to make a space where dialogue might take place. One of their complaints was that we had done our work in secret as outsiders. Not only was almost every part of the film previously published and widely seen, but we also wrote many pieces about our work (like this one) as we made it, and we talked about it in several local interviews about our film “Working In Protest” which screened at the Carrboro Film Festival in November. Further, we told the collective filmmakers and their impact producer exactly what we were doing, and shared a rough cut link back in November as well.

No Comments