22 Jun Dr Sarno Was a Trauma Informed Care Pioneer

Recently I saw a tweet from an editor seeking science/medicine pitches because he was taking over a new full-time role at a newspaper. I sent him a note with a link to our film “All The Rage,” suggesting that he either allow me to write a first-person piece about our experience of making and distributing a film that focused on the work of Dr. John Sarno, or to see if he was interested in having someone write a story about it. He wasn’t. Still, I’m grateful for the back and forth that we had because it helped me articulate some ideas about why Dr. Sarno’s work was so important, as well as what his dismissal by the medical community reveals about how systems often create barriers that go unseen by those within the system. Specifically, the conversation helped me to realize that Dr Sarno was practicing in a trauma informed manner decades before anyone had named the concept. Since the medical system didn’t give credence to the import of emotions nor the impact of trauma on our physical bodies, his approach ran counter to prevailing beliefs, leaving him quite isolated. In the 4 years that we have been working on getting our film out into the world, we have been trying to highlight just how significant and ahead of its time his insights were.

The dismissal of Dr. Sarno is rooted in the idea that he didn’t take a scientific approach to medicine because he didn’t do randomized controlled trials to prove his theory that repressed emotions, related to early childhood trauma, were a cause of pain. What is ironic about this situation is that the reason he came to this conclusion in the first place is that the treatment methods he was taught early in his career had not delivered satisfactory results, causing Sarno to take a closer look at the basis for those treatments. None of the treatments he was taught – things like bed rest, traction, physical therapy, and electric stimulation – had seemed to help permanently improve patients’ back pain. When he looked for research to support these treatments, he didn’t find anything of note. There was no scientific basis for the treatments.

Dr. Sarno entered the medical field just after World War II. This was a period when the bio-technical approach to medicine was picking up steam. As the focus on double-blind randomized controlled studies took off, awareness of emotional factors became more limited. Emotions are messy and complex, and therefore not suited to be easily studied in a randomized control trial where the ideal of scientific exactitude is sought. Rather than deal with the complexity of emotions, the science-based approach to medicine simply ignored them because their complexity made the data less clear. Dr. Sarno went to medical school when the ideas of Dr. Freud were not completely out of vogue, and he carried that emotional awareness with him as he entered the practice of medicine.

After spending about a decade working in the first group practice in NY State that he helped organize, Dr. Sarno moved to the Rusk Institute at NYU where he spent the rest of his career. There, he continued his training in dealing with back pain. When he became frustrated with the limits of the methods he had been taught, he took a long look at his patients’ charts and found that 80% had two or more other health issues that were known to be psychosomatic, or had a mind body connection. These included skin issues, migraines, colitis, depression, and other gut issues. He began to talk with his patients about what was going on in their lives and noticed that many of them were living in stressful situations, but were taking pains to put a positive spin on them. They tended to be people-pleasers who were disconnected from their own needs. For example, when asked if there were any major stressors in his life, one man said that there weren’t. However, Dr. Sarno then asked for more information. It turned out that the man’s mother-in-law had come to stay for a week, but never left. She’d been there for six years. He explained that it was fine, though, because his mother in law helped take care of the kids. When Dr. Sarno pressed further, the man admitted that it was a little frustrating to have his mother-in-law living with them. A few days later, the man’s back problems were resolved. Dr. Sarno was shocked to find that this simple intervention yielded such powerful results.

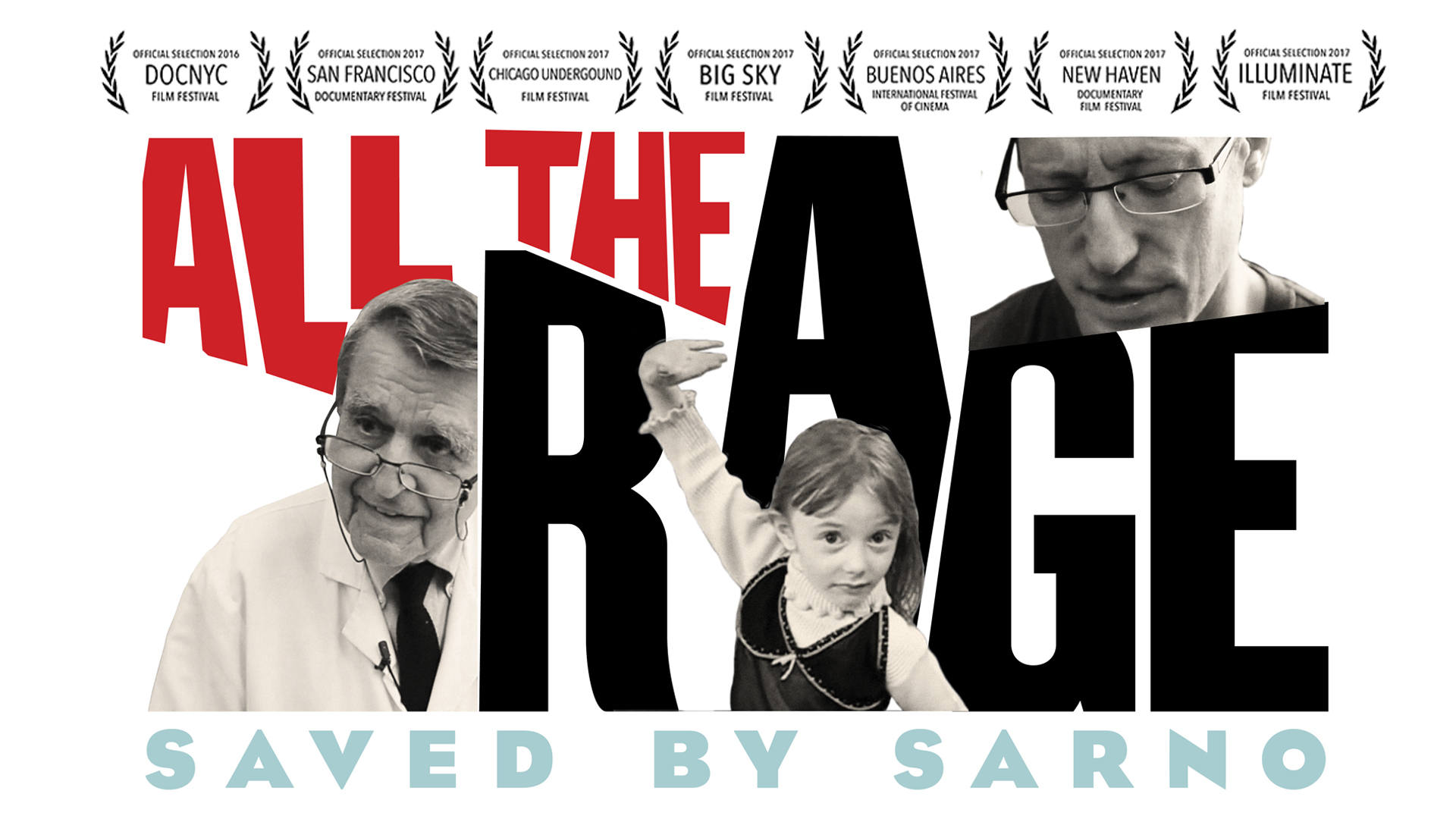

He postulated that the pain was a distraction from emotions that felt dangerous due to trauma from childhood. We often think of trauma as the result of terrible circumstances or abuse. However, a child who feels unsupported, or unseen, or has parents that are emotionally unavailable, might develop coping patterns to deal with the pain of that disconnection. This can involve disconnecting emotionally to avoid those overwhelming feelings. These unconscious reactions to one’s emotions can then carry on throughout their lives. Helping his patients to understand the connection between the feelings that they were having trouble accepting and their pain often led to the resolution of the symptoms. Our film about Dr. Sarno is called “All The Rage” because Dr. Sarno connected the pain to unresolved rage and other powerful emotions from childhood that keep people stuck in these unconscious patterns.

The newspaper editor’s response to our pitch about Dr. Sarno highlighted many of the issues we’ve faced in trying to get our film seen. First, he said that he thought it was “a little too late” to do a story about Dr. Sarno. However, he stated that he was kind of interested in a story about people who had taken up Dr. Sarno’s mantle and wanted to know if I could give him the lay of the land on whether anyone has been doing the scientific research. I responded with a more thorough description of what I wanted to write, or see written as well as some information on those who had followed Dr. Sarno. He pressed for more direct information about the latter. This prompted me to write a much longer response, which he ignored. That email then inspired this post.

The editor’s response wasn’t shocking, but it was disappointing. In fact, it made me think more about my own relationship with trauma and illness. We first started to work on our film about Dr. Sarno in 2004 but we quickly hit a wall. While we were coming off a film that had found some success, and had even been shortlisted for an Oscar, we could not find any support for this project. Ironically, I had come to see Dr. Sarno for my own completely debilitating leg pain, which I can now see was directly connected to the deep frustration of trying to get that previous film seen. It wasn’t just the film. We had a baby two nights before the film premiered in the US, meaning my wife’s water broke hours after we finished the film. The stresses of life piled up like so many rusted out cars in a junk yard.

While seeing Dr. Sarno helped me on a path of healing, it didn’t completely cure my pain. I saw making the film as a way to gain deeper personal insights. My own experience shows how difficult this can be, especially when childhood trauma is involved. To make a long story short, not only could we not find any support for our work, we also couldn’t figure out how to tell Dr. Sarno’s story. Eventually we put the film on hold.

I continued to slowly heal. Then, about seven years later, when we had another film to release, I pushed myself as usual. Just before that film, “Battle for Brooklyn” opened I started to get terrible pain in leg. Despite having trouble walking I did a q and a at every screening on opening weekend. Despite a successful opening, and many stellar reviews, no other theater would show the film. Once again the frustration caught up with me and I was crushed to my office floor, and unable to sit up for weeks. This was when I realized that I had a lot of work to do, and that I would have to be a character in the film in order to get it made. Both of those facts provided leverage for me to lean into the work with more present awareness. I learned a great deal from the pain. When it flared up I knew to be more aware of what my body was reacting to. That was profoundly useful, but it was not, and is still not, simple nor easy.

I had a lot of time to spend reflecting on my life and childhood. Part of my healing process involved learning to let go of some of the anger that I felt towards my parents, which involved letting go of the expectation that they be perfect. Finding that empathy also helped me to make a little more empathy for myself, which made it possible to process and let go of some of habitual behavior patterns. Exploring that process while making the film helped others to connect with their emotions as they watched it.

When we started back up the process of working on the film back in 2011 we found that a number of other doctors had made the same connection to childhood trauma in various fields. Dr Gabor Mate had written the book “When the Body Says No” which focused on how the repression of emotions was central to the development of many auto-immune conditions. He talked extensively about the effects of childhood trauma. Dr David Clare had published “They Can’t Find Anything Wrong” about his recognition that many gut issues were related to childhood traumas, and the repression of those uncomfortable feelings and thoughts. We included both of them in the film.

We also found the powerful work of Nadine Burke Harris who came to see that she was mostly treating the symptoms of stress in her Oakland clinic. Her discovery led her to stumble on the ground breaking ACE study. ACE stands for Adverse Childhood Experiences. In this 1991 research study doctors collected data on 17 thousand patients. They found that people who had been affected by 4 or more adverse childhood events like having a drug addicted parent, a parent in prison, or abuse in the home were wildly more likely to suffer from a wide range of diseases. This study was the first that conclusively connected childhood trauma to profound impacts on health. Unfortunately it took decades for the medical system to begin to pay attention to it. Now it’s paving the way for a revolution in a trauma informed approach to illness. Still, there is great resistance to this approach from the larger medical and patient communities.

One thing that is significant about Dr Sarno’s awareness is that he focused directly on the less dramatic traumas of childhood and how they might affect us. Decades before the term was in use, he was practicing in a trauma-informed manner. However, since these childhood traumas were seen as something to be dealt with in psychotherapy, there was very little acceptance of dealing with them from a medical perspective and Dr. Sarno was dismissed by his colleagues and the press. So, he toiled away in solitude, successfully treating patients, and publishing books about his work that helped hundreds of thousands of others heal as well.

My father was one of those who healed from terrible pain by simply reading his book. Later, my brother was saved from debilitating hand pain by seeing him in his office. I then read the book, understood the basic emotional connection, and banished my back pain for a decade. Later, when it re-emerged and crushed me, I struggled to fully heal despite seeing Dr Sarno in his office. Resistance to our emotions can be powerful. When we are taught as young children that our emotions are not acceptable, we bury them in order to get the care that we need. We try to become the people our parents need us to be rather than the people we need to be. It can be very difficult to re-connect with these feelings that we have banished.

We finished “All The Rage” in 2017 and I have spent the past 4 years trying to get it out into the world. In that time I have been unable to get anyone to write about it. Dr. Sarno passed away 4 years ago, on June 22nd. The following day, unaware of his passing, we opened our film in NY at Cinema Village on what would have been his 94th birthday. The NY Times had never written about him before the review of our film that came out on the 23rd. Without that review, it’s unlikely that they would have given him an obituary, as they generally measure newsworthiness of a subject by whether or not they have covered that person in the paper. We found about his passing on the 24th, and word started to spread through the audiences that day as several of his colleagues and former patients began to get the news. Despite the significant impact that he had on the culture, and our profound efforts to get the film seen, in those 4 years we have been unable to get anyone to write about Dr Sarno and his work, or our film. It’s been seen in 95 countries now, but it exists in the shadows, outside the awareness of mainstream media culture. It’s not for lack of trying. We hired 4 of the best publicists in documentary and I have continued to make efforts like the one above to get people to write about the film.

While we wove ideas related to trauma informed care into the film, my discussion with the editor helped me to see just how significant Dr Sarno’s work was in relation to that idea. However, because his work didn’t get much attention from his colleagues, the medical system, or the press his insights related to trauma awareness have largely gone unrecognized. I’d like to see that change.

After the editor made it clear that he wasn’t interested in Dr Sarno, but might be interested in writing an article himself about the scientific research that follows up on is work, I responded with a note gently pushing back on the idea that he wasn’t grounded in science. Doing so helped me to articulate a little more clearly that Dr Sarno was practicing trauma informed care well before others were thinking in the same manner. I spent a lot of time on that letter so I’ll just post it here. Apologies for the fact that a little bit of the information about Dr Sarno’s history was already stated above. I did not hear back from the editor after this note.

Dear Editor

Dr Sarno’s ideas are being confirmed through several studies, including one collaboration between Tor Wagner and Howard Schubiner that is close to being finalized.

I’d like to gently push back on the idea that it’s “a little late” to examine the import of Dr Sarno’s work, as well as the idea that his work wasn’t rooted in a commitment to the scientific practice of medicine. Dr Sarno came of age in medicine when emotions were still seen as a factor to consider when getting the fullest picture of a patient’s health, so it shouldn’t be a surprise that he included the patient’s emotional situation in his treatment practice. As medicine increasingly focused on double blind trials, emotions were increasingly disregarded because of the difficulty of controlling for their complexity. Over time, emotions slowly disappeared from the medical conversation. It’s only in the past decade that they have begun to be reconsidered, and that the idea of trauma-informed care has begun to rise in importance. If you look closely at Dr Sarno’s practice, you’ll find that this is the approach he used throughout his career.

Dr. David Clarke, the gastroenterologist who wrote “They Can’t Find Anything Wrong,” stumbled onto this awareness when he had a patient that wasn’t responding to any treatment. He ran into a psychologist colleague on the elevator and lamented about his frustration, suggesting she stop by and see the patient. A couple of days later, he saw his colleague again, asked how the meeting went, and found that the patient had been released. He was shocked to hear that after the psychologist helped the patient make the connection between major family stressors and her gut problems, the pain that had kept her on a high levels of pain meds for weeks had melted away. After that he started to talk to his patients more extensively, and found that pattern repeating. Soon, he was being sent every difficult case in Oregon. His book is based on 7000 cases, many of which were people who had chronic issues for years. As Dr. Clarke points out, nothing in his training prepared him for what he discovered by happenstance. Now he spends the majority of his time educating other clinicians about the import of understanding the import of emotional factors when trying to help people to heal.

As Dr. Sarno honed his understanding of the connection between stress/the repression of emotions, the majority of his colleagues across the country and the world continued on in the same manner, focusing solely on physical symptoms and findings, despite the fact that these practices were not developed through rigorous scientific study. At the same time, the introduction of technologies like early scanning devices, and later MRI’s, led to a host of more invasive techniques including surgery and steroid shots, based on the assumption that what they were seeing on these scans was the cause of the problem, and that steroid shots seemed to help some of the time. To be clear, for years no one bothered to do any double blind studies to make sure that these assumptions were correct. As Dr. Sarno witnessed this change, he was frustrated by the steady stream of patients who came to him with scans that did not correlate with their symptoms. He couldn’t find any studies that showed that the herniated discs were causing the problem. He referred to them as “normal abnormalities”. He also found no studies that showed steroid shots were more effective than placebos (this link is to an article by Dr Schubiner in Psychology Today). Given these facts, continuing to use surgery or steroid shots would not seem to be indicated by a scientific approach to medicine. However, despite all this evidence medical practice has relied almost exclusively on these techniques which have been called into question through science. While medical groups continue to put out statements suggesting that the use of MRI scans be limited in the case of back pain, these calls are largely ignored. Further, as Tbilanow reported in 2008 the surge in spending on back pain showed no benefit.

Dr. Sarno was not alone in his awareness that the data on back pain was problematic. Dr Nortin Hadler detailed all of the problems with the treatment for back pain in his award-winning book, “Stabbed in the Back”. When studies did begin to come out looking at the correlation between what was seen on MRI scans and pain, the data was quite clear. There was no causal correlation between what was found on scans and pain. The drug compounding crisis of a few years ago, when dozens died of infection after contaminated shots led to meningitis, illuminated that the shots were not only dangerous but also questionable. As the linked article states, ” ‘Not only were these people killed, but there was no ethical reason to give this treatment,’ said Dr. William Landau, a professor of neurology at Washington University in St. Louis, referring to those who died of meningitis.”

Gina Kolata, of the NY Times, wrote a series of articles dealing with back pain, imaging, and treatment. Over the course of two decades, she wrote article after article detailing studies that supported what Dr. Sarno was saying: that the scans are a bad idea because people are making assumptions about supposed abnormalities causing pain when there was no data to suggest it was true. In fact, in one of Ms. Kolata’s more recent articles from 2017 she writes:

Scans, like an M.R.I., for diagnosis are worse than useless for back pain patients, members of the group said in telephone interviews. The results can be misleading, showing what look like abnormalities that actually are not related to the pain.

She goes on to say,

Added to the problem are the incentives that push doctors and patients toward medications, scans and injections, Dr. Deyo said. “There is marketing from professional organizations and from industry,” he said. “We have the cure. You can expect to be cured. You can expect to be pain free.”

Medical insurance also contributes to the treatment problem, back experts say, because it does not pay for remedies like mindfulness training or chiropractic manipulations which, Dr. Deyo added, “are not cheap.” “Even if doctors want to recommend such treatments, there is no easy referral system.” Dr. Atlas said.

“It is much easier at Mass General to get a shot than to get a mind-body or cognitive behavioral therapy,” he added.”

Back in 1994, she reported pretty much the same thing with quotes from the same Dr. Deyo. In 25 years – despite increasing mountains of evidence – unproven cortisone injections, pain pills, surgeries, and diagnostic imaging exploded in use and cost, which has severely compounded the problem. The rise in cost of incidence of chronic pain from 1984 to 2011 was astounding. At the same time, Dr. Sarno quietly healed thousands of people without drugs or expensive and invasive procedures. Instead, he did exactly what Kolata’s 2017 article suggests in its closing paragraph,

Dr. Weinstein has a prescription: “What we need to do is to stop medicalizing symptoms,” he said. Pills are not going to make people better and as for other treatments, he said, “yoga and tai chi, all those things are wonderful, but why not just go back to your normal activities?”

“I know your back hurts, but go run, be active, instead of taking a pill.”

My point is that there was not much about the treatment of back pain that was securely rooted in science over the past 30 years, yet Dr. Sarno is routinely dismissed because he wasn’t doing randomized controlled trials. Dr. Weinstein is quoted as an expert, and Dr. Sarno never showed up in any newspaper, despite selling millions of books, because he was quietly doing his work without any press releases. What makes Dr. Sarno’s work so significant is that he wasn’t just telling people that their pain was all in their heads. Instead, he gave them the insight that there were things going on emotionally that the patients were often not aware of because these problems were rooted in trauma from childhood. In other words, he had been taking a trauma-informed approach to back pain since the late 60’s. His practice involved a thorough physical examination to rule out a more serious issue like a tumor, a fracture, or other medical issue. He said that his “prescription was knowledge”

Dr. Sarno helped patients understand just how powerful the mind body interaction was through lectures, personal discussions, and small group meetings. If he felt that the patient’s emotional issues were more serious, he sent them to one of the psychotherapists he worked closely with. Over time, he phased out physical therapy because he found that it kept people focused on their physical symptoms rather than the emotional patterns and stressors that were causing the pain. He combined his medical knowledge with an awareness of the import of emotions. This is what the further research is proving to be a successful approach. Everything that Dr. Sarno developed through careful and thoughtful engagement with his patients is being borne out by research, including that which has been done by those who have followed him.

I believe that this story is much broader than just Dr. Sarno. Trauma awareness is rising in a whole host of fields. The ACE Study confirmed the impact traumatic circumstances can have on our health. Doctors who specialize in dermatology, gastroenterology, general practice, addiction, and every aspect of psychology and psychiatry are building on these insights. Dr Sarno often discussed how his theories were connected to other types of illness but he only treated people within his area of expertise.

Through trial, error, research, and insight, these other practitioners have came to see that trauma, emotional blind spots, and relationship patterns formed in childhood, often played a major role in many health issues. While few of them knew of each other’s work when they had their insights, their public efforts to tell the story is beginning to connect them with each other. What connects them all, beyond their insights, is that they have had to take their ideas, observations, and research directly to audiences because the medical system hasn’t valued their contributions. Dr. Sarno was doing this in the wilderness. Now, patients are finding the ideas through TED Talks, popular books, and online lectures. While you point out that the mind body connection is widely understood to be true, it still has not had a significant impact on practice. Doctors are starting to accept the idea, but they also face significant pushback from patients.

Currently, Dr. Gabor Mate, who is also in our film, is doing a very popular online event about dealing with trauma. The Holistic Psychologist (Nicole LePera) has a NY Times best selling book about uncovering trauma-related relationship patterns, Dr. Clarke’s book deals with trauma and gut issues, Bessel Van Der Kolk talks of the body keeping the score, Dr Nadine Burke Harris re-oriented her work to deal with the stress of trauma and found great success, and Hilary Jacob Hendel’s book “It’s Not Always Depression” is helping people to connect with their underlying emotions. As I wrote in my previous note, Dr Wayne Jonas’ book discusses the idea that 80% of healing comes from within. While all of these people are respected within their fields, they have had to step outside of their systems in order to tell their story to a wider audience in order to have it begin to impact practice.

Michael Galinsky

Heiner M.

Posted at 14:06h, 21 NovemberHello Mr. Galinsky

Translate with Google.

My Name is Heiner M, from Germany

I’ve just seen your film – All the Rage – and I’m thrilled. So far I thought that I was the only one who felt as intensely as Dr. Sano deals with the mind body syndrome. To this day I have received nothing from Dr. Sarno should be read.

In short:

I began to be interested in psychology 12 years ago. I wanted to find out why my brain makes such wild leaps of thought all the time. I didn’t want to say more sentences with which I sometimes hurt other people emotionally.

Assuming that my behavior was not inherited, these faulty connections in my subconscious must have come into my brain in a different way. After about a year I understood that these connections had been saved in the subconscious for my childlike brain through too many illogical experiences. These missing connections then started in response to a keyword or a key reaction. Then there were outbursts of feeling that I didn’t even notice or that I could control.

In order to free myself from these emotional outbursts, I needed another 4-5 years until I was able to experience the first successes of these emotions subside.

As Dr. Freud had already written that everything psychosomatic begins at home.

What happened next was INCREDIBLE !!!

As the emotional outbursts subsided, my physical problems also subsided. The back pain disappeared, the dark spots on the skin disappeared, the eyesight improved again, the gray hair became dark again, the intestinal problems disappeared, the skin became smooth again, the wrinkles disappear and so on …

I think you understand how it all relates! Dr. Sarno probably had too little time in his life to delve deeper into that of people’s psychos. He also had to do his doctor’s job every day.

The crucial point is the expansion of consciousness. Think of your father. Was her father born with his emotional outbursts? No!!! Her father got these emotional outbursts from his parents’ house. Her father’s parents took her from her parents’ house.

If you can now look at your father from a different angle after these sentences, you expand your consciousness. Should a shiver of feelings run down your spine now, your subconscious tells you that it has understood the change in consciousness. Wait a few days to see whether you can feel any changes in the emotional area.

With correctly formulated sentences, you can already help people to think more consciously through interviews in a documentary film.

Thank you for the documentation !!!

Kind regards

Heiner M.