02 Nov The Commons

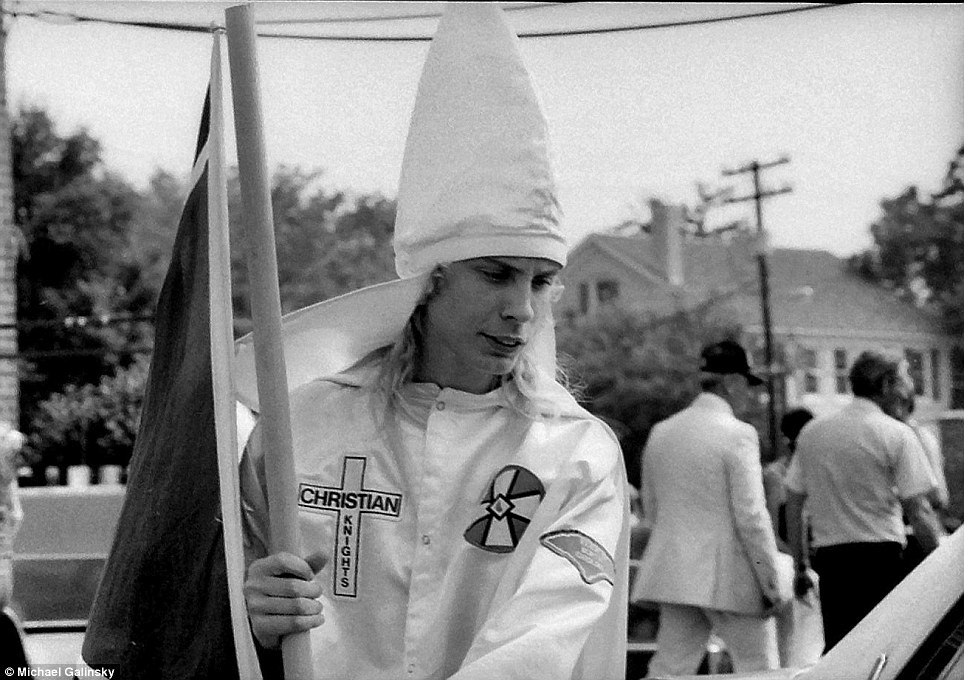

Before I made films, I made photographs, and those photographs were related to documentation. My first shoot was at a Klan rally and my first project was documenting people in malls. At around the same time, I also started to shoot bands and that gave me the first real outlet for my work. Sharing those images with fanzines and with the bands themselves was a form of communal communication, as they connected me to a broader group of artists. Before the internet, our music community “commons” consisted of rock clubs, record stores, and other places where music fans gathered. Ideas were further spread through fanzines and videos that were traded through the mail, as well as the aforementioned clubs and record shops, rather than through email links. At the time, there was a strong intersection between the political and the artistic as large sections of the underground music world were politically active.

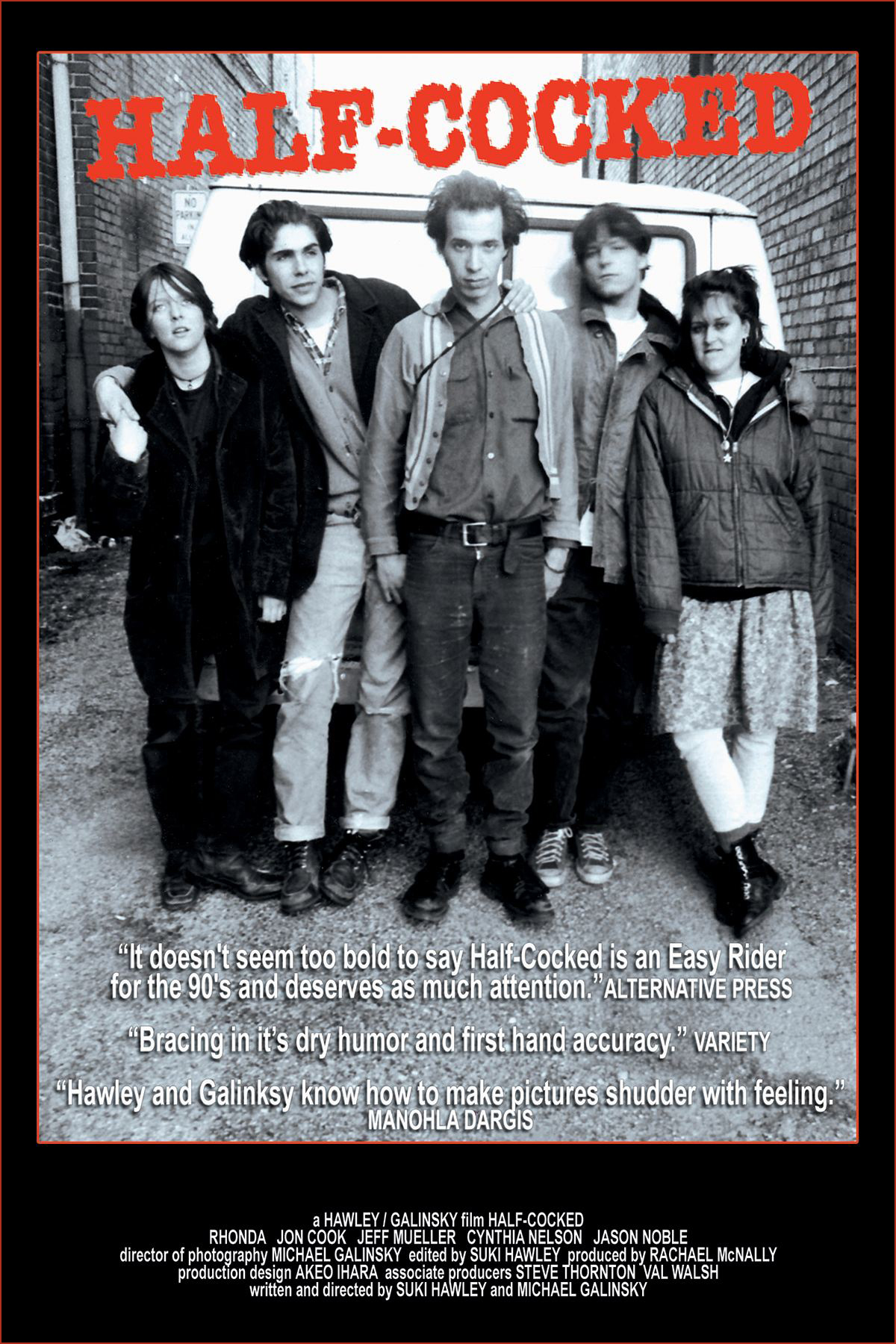

In 1994, the internet was starting to wheedle its way into our lives and affect our sense of the common space. The distinction between online and offline was still profound, and etiquette around online communication was starting to take shape. Twitter and Facebook were both still a long ways off. In that year, my future wife Suki and I made a film about the music community. It was an inside baseball look at the semiotics of indie rock- a vaguely navel-gazing work wrapped up inside a somewhat traditional movie structure wherein some kids steal a van full of music gear and head out on an adventure, ultimately becoming a band. In the film, almost everyone was playing some version of themselves, so it was essentially a hybrid documentary that was designed to capture the essence of the music scene just as much as it was to tell a story. Making a film about our own community was in some sense a political act. At the time major labels were swooping in and plucking bands out of the underground. Before that world was destroyed, we wanted to document it so that it would not be lost. A couple weeks after we shot the film, Kurt Cobain was dead.

Twenty-five years later, we’re still making films and still playing with the line between storytelling and documentation. Given the political climate and the impact that online communication has had, we’re thinking a lot about the idea of “the commons”, specifically the physical space, and how ideas get exchanged in such a divisive environment.

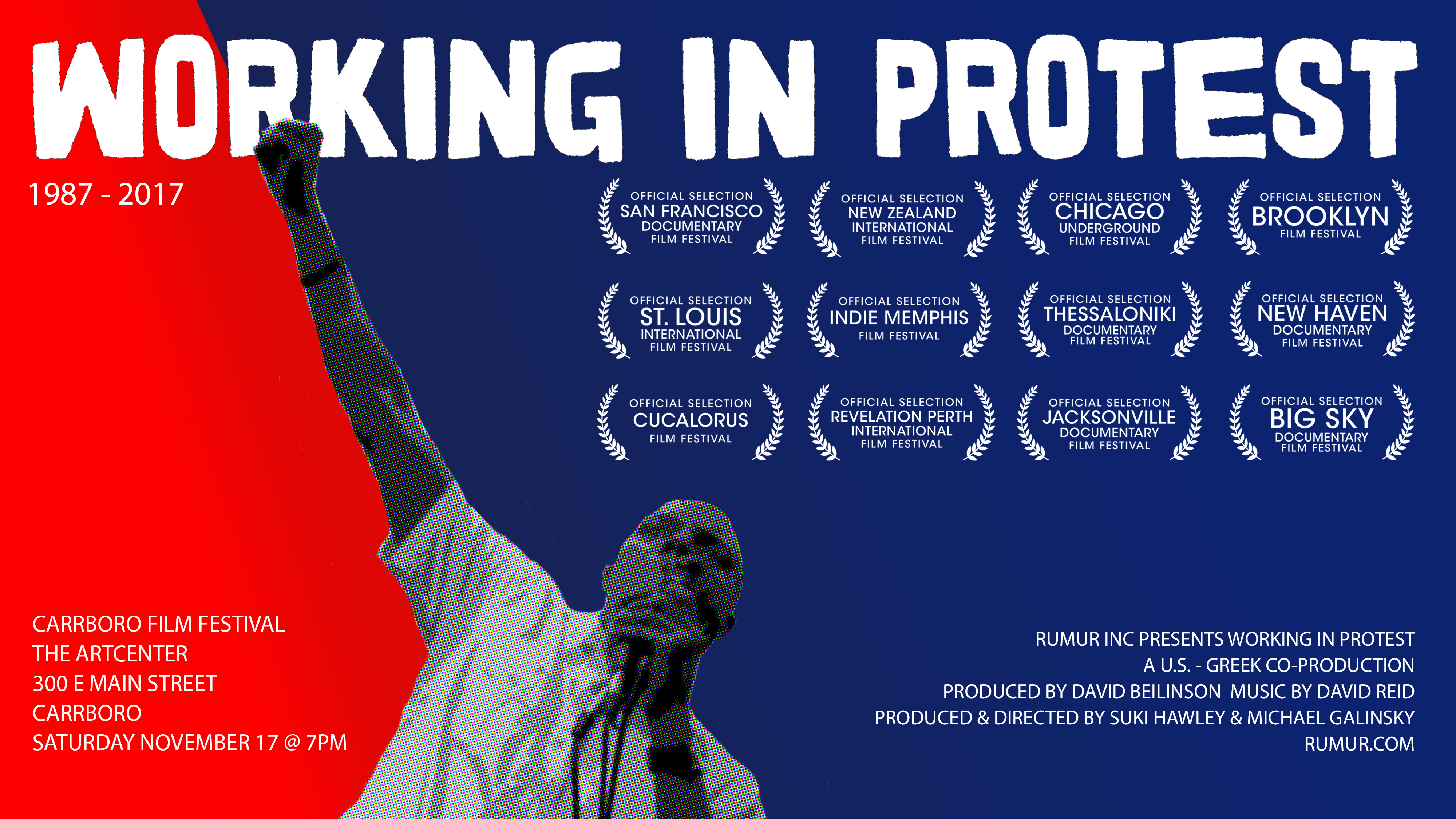

Our last completed film, “Working In Protest,” was constructed partly from work we made over the past 30 years, and partly from work we started to shoot around the election – once we knew we were making a film about protest. This work was a bit more focused in its approach to documenting in an observational manner. In other words, the more we shot, the more we understood what we were shooting. “Working In Protest” is interesting in what it tells us about protest by examining it as a continuum. We see a rise in the militarization of police, as well as an increasingly fraught sense of the criminalization of dissent. By the end, we see the fracturing of dialogue. In “The Commons” those things are made even more clear.

Shortly after completing that film, the White Power protest in Charlottesville led to an explosion of action against Confederate statues in the South. In August of 2017, we shot several intense protests and quickly shared them with people. A statue in Durham was removed and we filmed the aftermath. We also filmed a massive protest of a Confederate statue on the University of North Carolina campus. Both of these short films were deeply immersive. We didn’t follow characters, and we didn’t try to explain what was going on. Instead, we wanted to create a sense of experiencing the protest and the debate first-hand.

After shooting those pieces we thought about making a larger documentary about the issue. We went and filmed for a bit as protesters staged a sit in at the statue a week or so after the initial conflict. A few months later we filmed another protest after it was revealed that UNC police were using undercover officers to gather intelligence. Ultimately we decided that it wasn’t our story to tell. (edit- I want to clarify that an immersive documentary made about the students that focused on them as characters- was not our story to tell. However, we were very comfortable documenting the active protests in the manner that we had been doing for many years) We found out that a UNC class was making a collaborative documentary and we gave them all of the footage we’d recorded up to that time to use. A few months later we saw their film and they had only used a few moments of the footage. Their piece was largely built around their own stories.

A year later, protest once again erupted on the UNC campus, and we filmed as protesters tore down the statue by hand. We rushed home and made a piece called “Silenced Sam” the was seen widely the following day because the local independent weekly shared it. We kept filming a week later when two pro-statue rallies in a row developed into increasingly violent protest. We once again quickly made pieces and shared them. The statue was down but the debate would continue. There would not be any clear and immediate resolution.

When we realized that we had a number of pieces that told a larger narrative we began to weave them together as we had done with “Working In Protest”. We started to consider developing some characters to bring people into the story – but ultimately decided that the theme that ran through the work was more about the meaning of the commons than it was the details of this particular story so we focused on the actions that took place rather than the individuals. The country has become so divided that it seemed as if there was no room whatsoever for discussion. The public space that had become a flashpoint of conflict. We also considered filming at some of the trials of arrested protesters, but that too felt outside of the common space. Having seen the students film, it was clear that they were telling that story that provided all of the much needed context, so we focused on keeping focused on the very immersive work we had been doing.

In 1994 when we made a film about the music scene, it was a story about something we were a part of. In this case, while we certainly identify with goals of those protesting the Confederate monuments, we are not a part of the protests. We are also not a part of the “media.” We are stateless. This has created some difficulty, as there is so much paranoia and tension that the protesters see us as outsiders because we are not clearly on their side. This reality further shapes our decision to stay on the outside of the events.

We decided to limit the contextualization so that it might be a more universal story. Having filmed a few quieter events that we had not edited, we wove those into the narrative to help give it a little breathing room – as well as some discussion that took place in that space. “The Commons” is coming together very quickly, and we hope to show it in the new year.

No Comments