23 Jan The Commons (Malls and The Klan)

The Commons Trailer from rumur on Vimeo.

When I start a new project, I rarely have a full understanding of how it connects to our other work. However, I have spent the last few years taking stock of what we’ve done, and where we are heading, and there are a lot of patterns that have emerged that make the decision-making process feel a lot less random. The other night, we showed our kids John Sayles’ film “City of Hope,” which is a film that Suki saw a dozen times at a dollar theater in LA when she moved there in 1991. It’s one of the first films she showed me when we started to date. We hadn’t watched it in probably 20 years, but as we did, we saw profound connections between that film and our documentary “Battle for Brooklyn” as well as our deep involvement with our children’s neighborhood school in Brooklyn. Aesthetically, our work is not connected to John Sayles’, but the themes and ideas clearly resonated in deeper ways that we weren’t fully aware of.

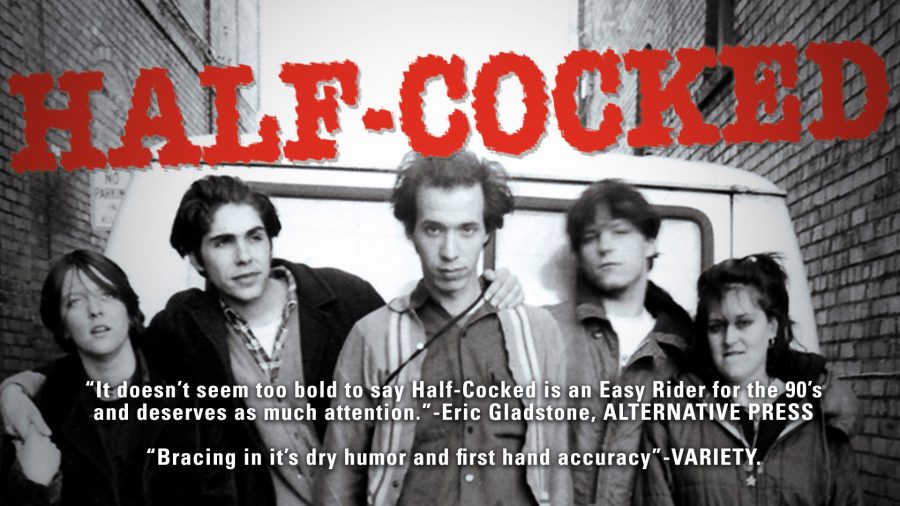

While our filmmaking started out by focusing on the music scene we were a part of, we quickly pivoted towards politically-oriented work as soon as we started to make straight documentaries (our first two films were narratives that had strong documentary elements). The first doc we made, “Horns and Halos,” focused on a punk rock publisher as he struggled to re-publish a discredited campaign bio of GW Bush before the 2000 election. We came to make the film because the publisher was connected to the NY music scene. Most of our documentaries have dealt with political issues on some level, and all of them have dealt with subjects or ideas that challenge mainstream ideas and expectations, and the way we make them often subtly challenges the expectations of filmmaking. You can take the filmmaker out of the punk scene, but you can’t take the punk out of the filmmaker. I have always had a resistance to doing things the way they should be done. Even though I wanted to be a photographer, I chafed against the “gear-oriented” approach to making images. Even now, as I shoot a lot for our films, I have resisted getting a professional lens for my camera. I have a decent older Nikon zoom lens that isn’t stabilized. This means that when I’m shooting protests, the footage is often a little shakier and less in focus than it could be. After each shoot, I vow to get a new lens because I feel silly wasting the opportunity to get more “professional-looking footage”. However, as we have started to share that film (“The Commons”) with people, I realize that the shakiness actually adds something it. It feels even more fraught and immediate than it might if the movements were smoothed out and every shot felt perfectly composed.

Shot over the course of a year and a half, “The Commons” documents a series of protest surrounding a Jim-Crow era Confederate statue. The title refers to the fact that all of the filming takes place in the “common space,” and the subtext of the project is as much about the idea of the commons as it is the particular issue being fought over. Recently, that film was invited to a festival and the programmers suggested also exhibiting some of the images from my first major photo project, Malls Across America. When I drove across the country in 1989, I was continuing a project documenting in a mall on Long Island that I had started in my first college photo class. At the time, I had a bottom of the line Nikon FG 20 with a sigma 35mm 3.5 lens (i.e. a really cheap wide angle lens that needed more light than a faster 2.8 or 1.4 lens). It still baffles me today that I would drive all across America and not make even the slightest effort to get a decent lens. However, when the images went wildly viral, I came to see that the imperfect-ness of the images was actually a strength. I don’t think they would have gone so viral if they didn’t feel a bit unprofessional. The lack of slickness make the images feel less like ART in a way that draws people in and makes them feel comfortable. I don’t think that the shakiness of the protest video makes people more comfortable, but it does draw them, and it adds to the verisimilitude of the footage. I will probably use software to steady a few shots, but I am inclined to mostly let it be.

When the festival suggested showing the mall images, it made a lot of sense because I had been thinking about that connection myself. When I went to shoot those images, I had already completed a major in religious studies because I took so many anthropology, sociology, and philosophy classes. At that time, I was thinking a lot about how the Mall was replacing the town square as the new Commons- it was a privatized “public space.” As a 20-year-old, I really hated the mall and all that it stood for, but I tried to shoot in a non-judgmental way. It would have been quite easy to make fun of the people and of commercialism in general. However, I was influenced by ideas related to anthropology and sociology and I considered the work important “documentation,” even as I tried to do it in my own street-photography way. When I finished the project and tried to show the slides to galleries, I literally got laughed at – partly because I had no idea what I was doing and I was showing the work to the wrong people. I did show the work at one rock show in a gallery that my band played at five years later, but they went into a box and I only found them 22 years later. Finding them and working with the images gave me new insight into the value of documentation, but also a re-connection to ideas related to the Commons. Around the same time, I began to shoot at Occupy and these ideas informed that work. Since then, I have continued to document with a renewed focus on capturing things in a way that has both present meaning but even more profound import in the future.

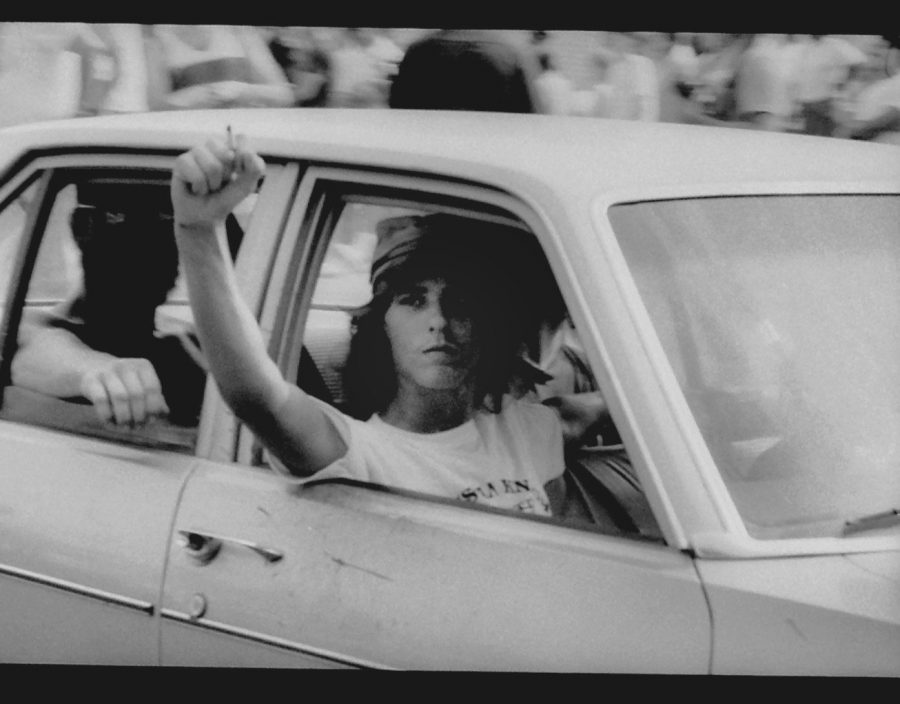

A few years after I found the mall images, I moved back to my childhood home and stumbled upon negatives from my very first photo shoot, a set of images from a Klan rally the day after I graduated high school. My experience with the mall images prompted me to scan them and share the set online. This led to discovery of sound that was recorded by the local radio station that day. We constructed a short film from the images plus sound that had a powerful resonance locally. Last night, as I lay in bed thinking about the mall images and their connection to “The Commons,” it struck me that the Klan rally, which took place on the main street of my hometown, began by marching up a short street that leads directly to the site of the protests against the “Silent Sam,” the Confederate statue which had become the focus of so much ire in our film. While I was aware of the connection between the Klan march 32 years earlier and the work we were doing on the film, I was kind of dumbstruck by how powerfully and intimately-connected that first shoot and my most recent project were. In both situations, I tried to be an impartial observer, but I was also aware that my own history, experience, and framing of the world could not help but have an effect on the choices that I made as I shot. In fact, the previous day, I realized that some of the younger kids who marched in ’87 were very likely part of the current group fighting to keep the statue where it is. The ideas that we form in our youth become foundational to our sense of who we are, and we will often fight dearly to keep that sense of self from being challenged too deeply. Even as I work to keep some “critical distance” intact, I also struggle to be present with what I feel.

At around 3 am, I composed an email to the festival suggesting that we print both mall images and Klan images and hang them together. The mall images are in color with a wide-angle lens while the Klan images are black and white and mostly shot with a slightly telephoto lens. They are aesthetically different in a way that I believe might be somewhat complementary, and combining the two sets creates a much more complex equation and space for discussion. In fact, I thought it would be a great idea to travel with the work and try to set it up for each screening to create a place where attendees might gather and discuss ideas related to democracy and the common space. The initial response was that this was perhaps too much. It probably won’t work out for that festival, but I’ll keep it in mind for the future – and I’m thankful for the suggestion because it led to a deeper understanding of the connections between the work.

No Comments