28 Aug The Journey Brings You Home

This weekend I started to think about the Wizard- the one behind the curtain in “The Wizard of Oz”. I began to make the connection between the story of the film and the story of how our emotions shape our relationship to the world, including our sense of our own health. I found a few clips from the film on-line that piqued my interest enough to prompt me to run to the library to pick it up. On Sunday we watched it as a family and though I have seen it before I was somewhat surprised by how deeply connected it is to the theories of Dr Sarno, who famously relied on his knowledge of Freud, in order to rediscover the power of the mind body connection in regards to treating back pain. While he was trained to treat back pain with physical modalities like bed rest and physical therapy, Dr. Sarno eventually came to see that the vast majority of his back pain patients were suffering from the repression of emotions rather than some structural abnormality. However, his understanding was met with disdain by his colleagues who had fully embraced a bio-technical, materialist, approach to medicine. Any discussion of health care that included the emotions was dismissed as unscientific “woo”.

“The Wizard of Oz” was released in 1939, when John Sarno was 16 and not yet a doctor. At the time, Freud’s theories were still largely in vogue and much has been written about the connection between the film and his work. Frank Baum’s book about Oz was released in 1900, the same year as Freud’s third book “Interpretation of Dreams” (interestingly Freud’s first book in 1891 was “Aphasia”. Dr Sarno’s wife Martha did groundbreaking work in speech pathology largely due to her understanding that aphasia had as much to do with emotional trauma as physical trauma.) While Freud’s ideas were already percolating culturally in 1900 when both books came out, his theories had become widely known by the time the film was made nearly 40 years later. A quick google search of “The Wizard of of and Freud” leads to thousands of college essays detailing various Freudian breakdowns of the film. In other words the idea that the movie has Freudian overtones is not a new one. However, when I watched the film through the lens of John Sarno’s theory, that repressed emotions are a major cause of pain, the film took on much greater meaning for me. In fact, the process of viewing it in this way connected me to my own emotions in ways that I hadn’t expected. Despite a good deal of work I personally have a difficult time connecting with my own sadness, and that night I found myself fighting off a headache and leg cramps that night as I tried to sleep. Eventually I realized I had to focus on that sadness. It was very difficult and I was up much of the night. I can’t say I was able to figure out what was going on completely, or that I was able to access the full feelings that were coming up. I did, however, learn some things about myself- small steps on a life long journey.

While Dr Sarno grew up in a fairly impoverished section of Brooklyn, a priest at his Catholic Church recognized his intellect and helped get him a scholarship to an elite private school. He then graduated from Kalamazoo college before entering the army during World War 2 where he worked as a medic. After the ware he went to medical school, where he learned the import of treating the whole patient rather than just their attendant parts. While the bio technical/materialist approach to medicine was beginning to take off, Freud’s theories had not yet been banished to the dustbin of medical history. In fact, when he began practicing medicine psychosomatic, or mind body, factors were thought to play a large role in a whole host of illnesses. When we interviewed Dr Sarno for our documentary he talked quite a bit about the history of science. He pointed out that in the 19th century, before Freud came along, all mental illness was seen as a disease of the brain. The materialist approach, which largely ignored the emotions because they couldn’t be quantified, measured, or seen came to see all mental illness as a chemical imbalance. He pointed out that the more things change the more they stay the same. While Dr. Sarno is often dismissed as a quack, who said that “pain is all in one’s head” (their quote not his), he was well versed in how the body’s physical systems work. In fact he came to hypothesize that the emotions were at the center of the problem because none of the treatment options he had been taught seemed to be very effective, there was little or no data to back them up, and more often than not, the physical explanation for the pain didn’t make sense. For example they might come in with a diagnosis of an L4 disc herniation, but they had pain in several different locations, none of which lined up with that finding. Further, the pain often travelled from one body part to another without a rational physical explanation. When he talked to his patients he found that many of them put a great deal of pressure on themselves to be “good people” or to “take care of others” which meant that they were also often repressing their own needs so deeply they weren’t even aware of it. He looked at their charts and found that 80 percent had 2 or more other psychosomatic illnesses. When he helped his patients to see the connection they began to get better at surprising rates.

As filmmakers we really struggled to find a balance between science and metaphor as we made “All The Rage” because while the information about Dr. Sarno’s work is important, a certain amount of metaphor is essential to involving people in a story from an emotional level. At first we put a lot of energy into getting a great deal of useful information about Dr. Sarno’s approach into the film, but we found that for people who were skeptical, that information only made them more skeptical. They wanted more facts, so we added even more information to answer their questions. After about a half dozen screenings like this we realized that the information wasn’t convincing to anyone who was already convinced otherwise, so we ended up taking out almost all of it. After that we found that even the most ardent scientific thinkers were more open to the concepts after watching. If a film doesn’t move us emotionally, then it is rarely something that we remember, nor something that causes us to think more deeply.

The first rule of scriptwriting is that conflict drives story. The second is that the level of conflict needs to increase. In the classic “Hero’s Journey” as described by the mythologist Joseph Campbell in “The Power of Myth”, almost every culture’s stories or myth’s involve the transformative journey of hero who must overcome increasingly greater odds, ultimately defeating dark forces in order to bring balance to the land. In the course of that journey the hero undergoes a transformation, or a state change, often from adolescence to adulthood (Luke Skywalker is a classic example). Stories give us the kind of road maps that we need to navigate our own transformations. Further, these transformations gain much of their power from our interaction with our community. For the past century movies have been a powerful form of ritual, and the best ones can connect with us on a very deep level. For example going to see Teen movies is a rite of passage for many young people, and the teens are both shaped by these films, and shape the next generation of them in turn through their interest and interaction.

“The Wizard of Oz” isn’t exactly a teen film, but it certainly is one of ritual transformation. At the beginning of the film Dorothy is essentially a frazzled teenager. I use the word essentially because it was a few years before the term was in regular use. When we first meet Dorothy she’s upset because a very mean neighbor has threatened her, saying that her dog Toto has bitten her. Dorothy rushes home to tell her Aunt and Uncle (who are likely her great Aunt and Uncle due to their age), but they are busy with farm chores and don’t listen to her. She then interacts with three farm hands on her Aunt and Uncle’s farm, and is saved by the least courageous of them when she falls into the pig pen. We are then treated to the famous song, “Somewhere Over the Rainbow”, a lullaby about lullabies that sets us up for both a trip over the rainbow and transformation from black and white into technicolor. Her dog Toto, ever at her side, gives her the kind of rapt attention that no one else seems to.

After the song, the neighbor Ms. Gulch shows up demanding Toto be put down because the dog has ostensibly bit her (it is indicated that no bit has really occurred). She has gone to the sheriff to get an order of removal so Toto can be put down. At first Dorothy’s Aunt and Uncle refuse to hand over the dog, but they are moved by the “lawful order”. The film has not given us the details of Dorothy’s having come to live with her Aunt and Uncle, but we can surmise that she has lost her father and mother. It’s also clear that Toto is an important tool for coping with that loss, providing her comfort and a sense of connection. In a nod to the conflict between morals and capital, Auntie Em rails against Ms. Gulch’s abuse of her wealth but refrains from telling her what she really thinks because she’s a “christian woman”. With that Ms. Gulch grabs Toto and rides off on her bike, but the Wiley Toto escapes from the basket and rushes home to his Dorothy. Dorothy in turn decides to run away in order to be able to stay with Toto. It is not a well thought out adult endeavor, but instead a childish whim.

They don’t get very far before they encounter a kindly carnival soothsayer who uses his “crystal ball” to convince Dorothy to head home to Auntie Em. She does so just as a great storm approaches. By the time she gets to the house the whole family, and the workers have entered the storm cellar and the wind is so loud they can’t hear her pleas for entry. She stumbles inside and is knocked “unconscious” and the film that we all remember begins. The first part is in black and white, but as the wind howls around her and she goes even deeper into unconsciousness she, and her house, land in a world of color- on top of the wicked witch. The first part of the film sets the scene, and the middle brings us into a world of metaphor. Dorthy, who is somewhat separated from her emotions kills the witch, but not on purpose, saving her from the guilt of her murder. The good witch sends her on her journey, and through a series of conflicts, which she successfully navigates, she transforms from a child into an adult. Along the way she meets the scarecrow, the tin man, and the cowardly lion- the three farm hands who all are stuck in between childhood and adulthood and she brings them on the journey as well.

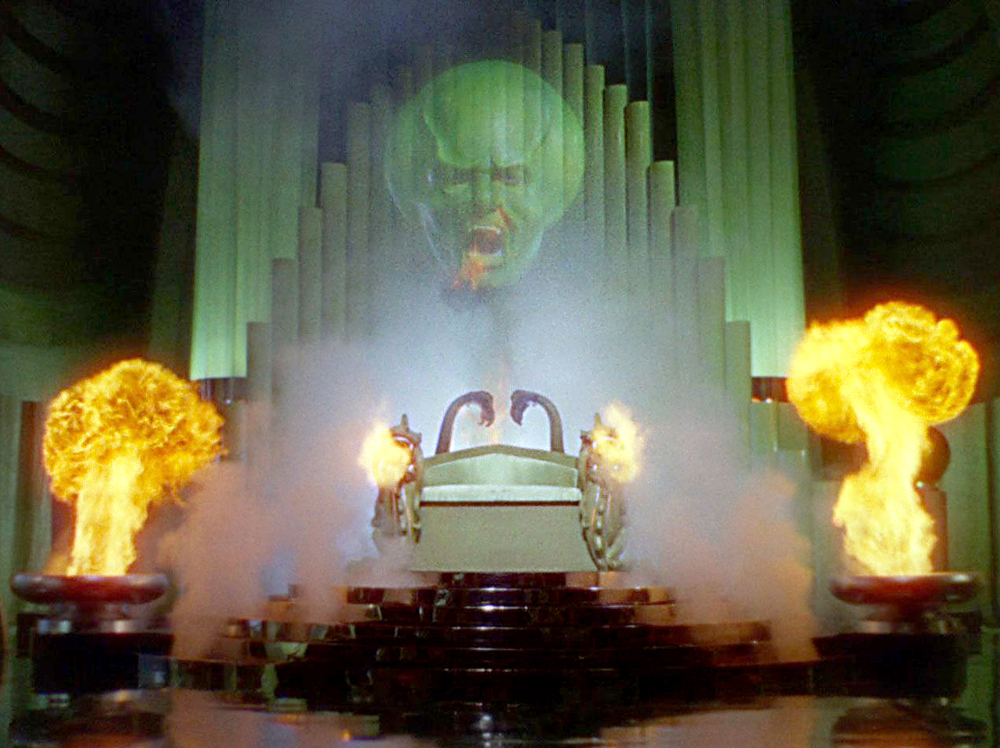

By the time they reach the Wizard they have overcome numerous obstacles, yet he is not ready to grant them the help that they request. Instead he sends them out on something of a suicide mission. They are tasked with taking the wicked witches broom which they do through a combination of bravery and luck. When they return to the Wizard with the broom he is unprepared for their presence. Toto quickly reveals that the great and powerful Oz is simply really just a guy pulling levers, yelling into a microphone, and blowing off steam. When confronted he helps the cowardly lion realize that he’s brave, the tin man discover his heart, and the scarecrow recognize that he’s a lot smarter than he ever thought. He agrees to bring Dorothy home, but Toto jumps out of the balloon and it floats away. The good witch then helps her to realize that she simply had to wish for home and she would be there. With that she wakes up- transformed.

Life is but a dream. Looking back at the film through the lens of Sarno’s theories, Dorothy heals herself from the trauma of losing her parents by fully embracing her new found family of misfits as her own. Together, they bond through struggle and through that process find a deep sense of healing. Each of them confronts a part of themselves that hasn’t fully made the journey from childhood to adulthood, and in so doing becomes a more fully realized person. In other words, the film takes us on a ritualized journey of transformation, the kind which helps the audience to connect to their own story through metaphor. This is where the film derives its great power. As we set out to make our film about Dr Sarno we understood that it is through ritual and metaphor that we find transformation. Information is important but no amount of information will change people’s minds if they are emotionally invested in avoiding that information.

Again, after watching the film I had a hard time sleeping. I focused on what it was about the film that might have bothered me. My father loved the film, but also told me how scared he was when he first saw it at the age of five. I too found it scary when I first saw it. As I lay in bed that night I tried to be with the fact that I still struggle with the loss of my father, and the film unconsciously connected me to that sense of loss in a myriad of ways. By focusing on, an working to accept some of that loss I was able to find a bit more calmness and eventually fall asleep.

The Wizard of Oz – Marco Montalto

Posted at 10:49h, 24 May[…] Available at: https://rumur.com/the-journey-brings-you-home/ […]