06 May Yoga

I started going to yoga classes last year, and over time, it has become an integral part of my life. There are times in our lives when we try to do something new and it doesn’t stick. A few years later, we might try it again and still find it doesn’t seem right for us. Then, at some point, we might find that we’ve tried it at the right time. For me, this happened with Yoga last March.

As often happens when I sit down to write a post, I find myself unable to simply knock out a quick pointed piece. One connection leads to another and soon it’s like a tangled ball of string. It becomes difficult, but not impossible, to pull out the different threads and perhaps save it. Sometimes though, I just have to accept it and let it be what it becomes. Unfortunately, that doesn’t make for quick blog reads, but I think that it does create more meaning.

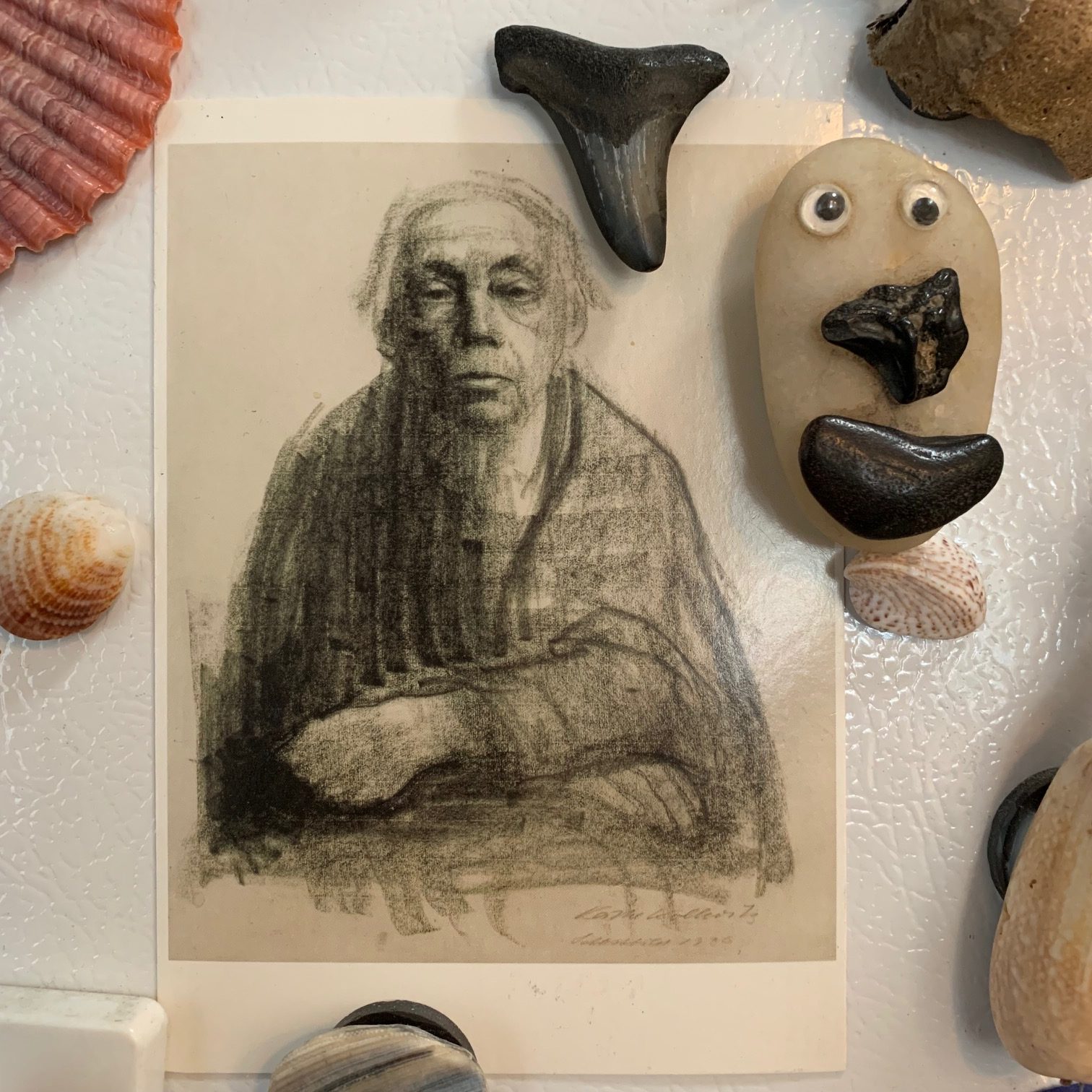

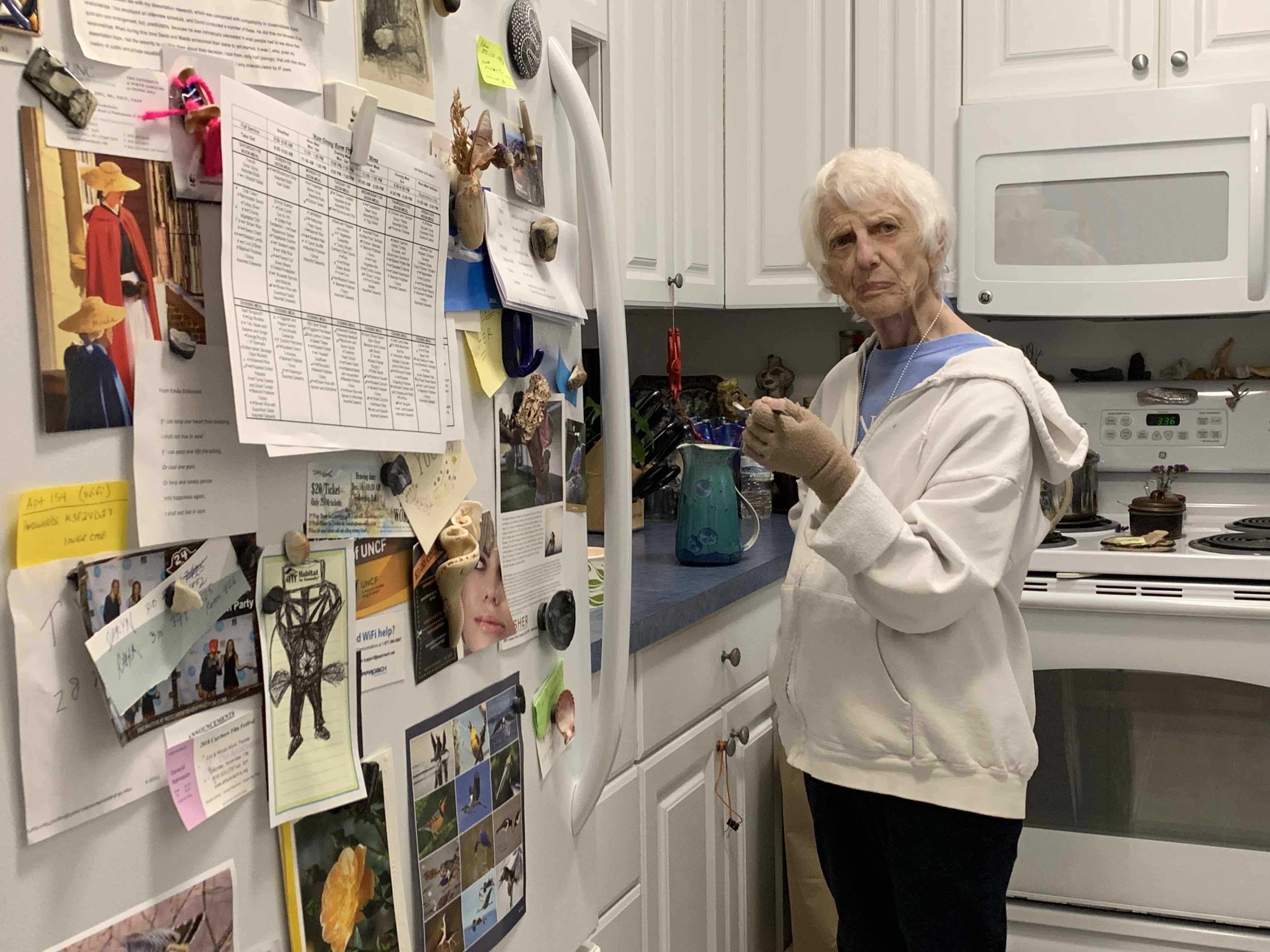

This was meant to be a post that was about how Yoga helped me make it through the past year. However, in order to understand the context of how that unfolded, I found myself adding more details, which led to more memories, which led to a profound shift in focus. This post is still very much about yoga, but it’s also more solidly about grappling with the unfolding of grief; specifically my efforts to be present with and accept my mother’s physical and emotional struggles with aging. As her memory and her health began to fail her, I concentrated on being present, being empathetic, and capturing photos and videos. I knew the photos would be tools that would help me process my experiences as well translate them in ways that might help others process their experiences. As I did this work, I shared some of it in real time, and got a very powerfully supportive response, which further shaped my sense of focus on figuring out how to communicate the ideas and emotions I was struggling to articulate.

Still, as much as I focused my energy on being present, there is a lot to be learned by looking backwards. As I have worked to put together this post, I have a much more clearly defined sense of how things transpired than I did at the time. When we are in the storm we often can’t see the waves. When things have calmed down we can see both the patterns and how our own perspective blinds us to so much.

Often, when we are confronted with impending loss, we slip into a hallway of limited vision. The losses may be physical, emotional, or related to our sense of identity. Sometimes we might hold onto a stock as the market tumbles because we can’t believe what’s happening even as we see it happen. Sometimes, we can’t see that our husband or wife is leaving our relationship even when everyone around us sees it clearly. Maybe we are so freaked out by a life change, like finishing school, that our perspective becomes more limited.

My father was hit by a car and died suddenly. He had been having some health problems at the time but we didn’t see it coming, and the shock was overwhelming. With my mother – even though I knew that her health was starting to fail her – I had a hard time accepting the course that was beginning to unfold. I saw ways of addressing her issues, like dealing with her depression and anxiety. However, she wasn’t committed to making the kinds of changes that were necessary. In retrospect, the story is so orderly that it almost feels pre-ordained, or inevitable. Yet, at the time, it was confusing – and at times threatened to be overwhelming.

This post originally started with my mother’s visit to the Emergency Room in January of last year. It was such an overwhelming event that was a clear marker of a shift in our lives. However, without the context of her earlier visit to the ER in December, or the increasing anxiety and memory loss that began to plague her the previous summer, that January visit was divorced from the broader patterns that were emerging. On one hand, I was intellectually aware that the anxiety and memory loss were both intertwined, and taking a toll on her. However, since I had very little ability to help her shift her perspective – or her behavior – I had a sense of helplessness that left me bracing for the next crisis rather than a sense of hope that I might be able to help her avoid the next crisis. Instead, I would use the moments of calm to steel myself for the next slightly panicked phone call. The January visit made me think of something I read recently about a situation falling apart as “unfolding slowly at first and then all of a sudden”. The “slowly at first” is hard to recognize until we’ve moved through it.

Again, I spent a lot of time dealing with my mother’s anxiety and memory issues in the latter half of 2018. Truthfully, I spent a good deal of my life learning how to deal with her anxiety throughout my life. It’s just that in the last six years, since my family and I moved back to Chapel Hill, that it was a fully-conscious effort rather than a reaction or response to it. In the last year, dealing with her anxiety was mostly in the form of long conversations in which I tried to help her see that the anxiety was complicating her memory, which was making her more anxious, thereby impacting her memory even more. In that chicken and egg story, I urged her to work on the anxiety. She assured me that she was, or that she wasn’t really as anxious as I thought she was. She was seeing a meditation teacher every couple weeks, but she really needed to be meditating several times a day to have a noticeable impact on her situation. I also suggested that she might consider taking some medication to help get it in check. She rightly was worried that it might affect her memory. Still, she was so concerned about losing her edge that she undermined her ability to have the edge she so badly wanted.

This story really starts in January 2019, with my mother’s ER visit that led to me spending 5 nights in the hospital with her. That was a very difficult experience that was followed by a number of other traumatic experiences and by March, I was really struggling. My friend Caroline was worried about me, so she came by to make me go for a run a few days in a row and then she picked me up and took me to my first yoga class. Over the years, I had tried to start doing yoga a number of times, but this was the first time it clicked. I needed the kind of grounding that it could provide, and while it was difficult, I knew that I was ready for the challenge of it. The class that she took me to was an intermediate one, which was way beyond my physical ability. However, the mental and emotional aspect of the class dovetailed with a lot of the meditative work I had already been doing. That work had prepared me for this practice, and I could clearly see how the physical piece could help me build on my efforts to find more balance in my life. It was a real struggle at first, but after each class I felt profoundly more settled than I was used to feeling. Soon, I was going a few times a week. Within a few months, I was often going twice a day on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

While it’s been a year since I began my practice, my mother’s struggles began about six months before that as her anxiety and memory loss started to bloom the previous fall. My mother had always struggled with anxiety, but she had developed all kinds of coping mechanisms that helped to mask the extent of the problem. However, in the fall of 2018, she fell into the kind of anxiety spiral discussed above; her memory issues spiked her anxiety which increased the memory issues, and so on and so on. I could see this play out in real time, but getting her to calm down and observe it for herself was not an easy task. However, it was a task I had been working on for years. So – while very frustrating – through meditation, and a practice of working on forgiveness and empathy, I was pretty well equipped to handle it for myself. In short, her struggles that Fall felt fairly normal to me, and within my capacity to respond without feeling too overwhelmed.

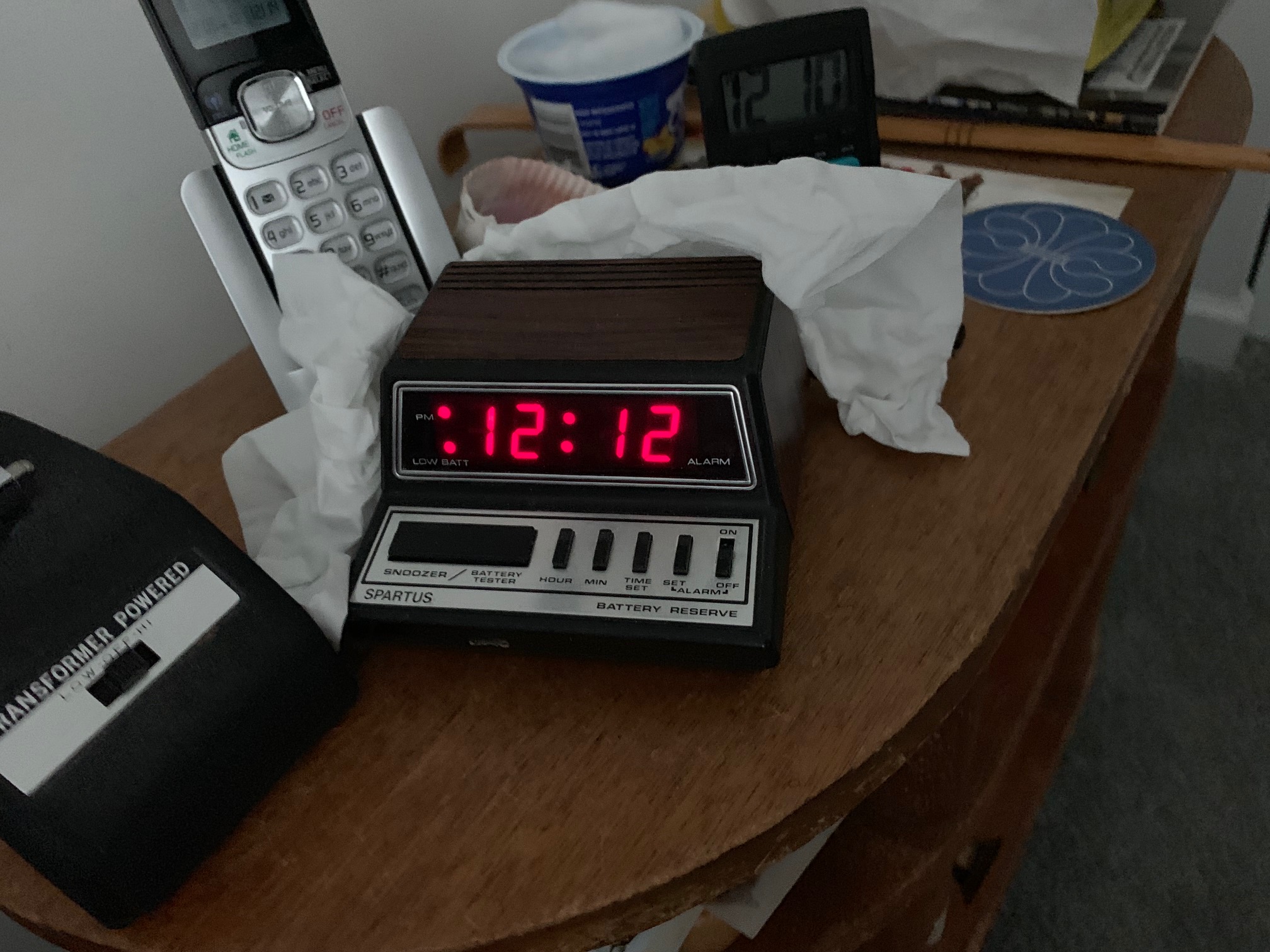

My mother was born on 12/12 and her anniversary to my father was 12/30. My father was hit by a car in January of 2006, so December and January had been kind of emotional months for her for many years. She was extra conscious of her age that fall because her 84th birthday was coming up. Almost every time we talked, she asked me with a sense of wistful wonder how she could have gotten so old. She had a hard time accepting things as they were. This was something I was working on for myself and I tried to get her to see the value in it, but she relied on old habits to navigate life, and she was sticking to her story.

Due to some freezing rain, school was closed on her birthday, so my wife, our daughters, and our exchange student went by for a visit. She was in rare form; cracking jokes, talking in a Queens accent and generally in a very good mood. It was a great visit all around.

Around 10 that night I got a message from my friend Marcela. She and her husband had spotted my mom wandering the streets, looking nervous. It turned out she was looking for her car and was very lost. She’d gone out to dinner with a friend who had walked her to her car, but she’d dropped a glove and insisted on going back to get it alone, which is when she got turned around. She didn’t want Marcela to call me, so they drove her around looking for it. I went uptown to meet them, and pulled my mother into my car to continue the search. We did some circling before eventually arriving back at the restaurant she’d visited. There’s a parking lot nearby that I had suggested we look through, but she had a distinct memory of parking on the street and instead that we focused on that. It turned out the car was where I thought it might be. She was pretty devastated by the whole experience and expressed horror at her perceived incompetence. I tried to assure her that she would be fine, but I didn’t get the sense that she was really hearing me.

The hardest part of the night was that she insisted on driving home. She almost wouldn’t let me follow her, but eventually agreed to my following her until she got on the main road. Some of the meditation and empathy work I had been doing was focused on coming to terms with the fact that, in order to maintain a relationship with my mother, I would have to accept some of her demands, no matter how unreasonable they seemed to me. As our parents age, there is a distinct shift in the power dynamic, but she was unwilling to find a way to shift in regards to accepting more support. She called me when she got home to let me know she had made it.

The next day, she had to take her car in to get it inspected. I didn’t realize just how stressful that would be for her. She got her longtime housekeeper to drive her to the dealership, but it turned out that she had knocked out all of the back lights and it was going to cost 1500 dollars to replace them. It was also going to take several days to get the work done. I didn’t find out about any of this until later that night when I got a call from her retirement community letting me know that she was on the way to the emergency room with overwhelming shoulder pain. As I drove there, I thought about how strong she was, but also how reactive. When we were kids, she would often scream out in pain if the water from the sink was too hot. She was always on high alert, which meant that we often had to be on high alert as well. I braced myself, preparing to translate my mother’s complexity to a medical system that isn’t so prepared to deal with interplay between the emotional and the physical.

When I arrived at the ER, I found her sprawled on a couch in the waiting room. She was in great pain and explained that she didn’t want to be there any more. It was unclear if she was talking physically or existentially. It was very hard to hear because I felt helpless, like I had no way of addressing the hopelessness she was articulating. She hadn’t fallen, but her shoulder had suddenly started to hurt so severely that it was determined she had to go to the ER.

After about a half an hour someone came to find her. In that time, she had barely moved and I wasn’t able to comfort her because all of my efforts only caused her more pain. It took a little while to get her into a wheelchair and into an examining room because every movement caused her to scream out.

I spent the last decade working on a film about the connection between emotions and pain. Armed with that awareness, it was plain to see that the stress of her birthday, losing her car the previous night, being forced to confront the fact that she had smashed all the lights in the back of her car, and simply trying to deal with all that stress, had caused her pain. Still, it made sense to do some x-rays just in case, but I did what I could to keep things from spiraling into a search for some unknown cause. I didn’t have the sense that the hospital was a healing place for her to be, but the doctor was helpful and understanding. As we waited for the X-Rays, her active anxiety spiked and she told me about the lights on her car and made sure I would call to check on it the following day. She also wanted me to check her phone to find out about the various appointments she had the next day. It turned out that she didn’t have any. She was feeling desperate about missing appointments because she was so anxious about her memory – her brain was constantly scanning for things she might be forgetting which only made her more anxious. Still, in this moment, her focus on these anxiety-producing feelings seemed to dull the pain.

Soon the X-ray came back. While it showed she had scar tissue from breast cancer 30 years earlier, they didn’t see anything that would explain the pain she was in. The doctor told her that she believed it was stress and that seemed to give my mother some relief. They gave her Tylenol and told her to see her regular doctor when she felt a little better. I took her home at around 2 am.

By the time we reached her cottage, the pain had largely abated. She carried so much stress in her shoulders that the flesh was hard like a super-flexed muscle so it wasn’t surprising that it would be sore. I was reticent to leave her alone after her earlier despair, so I let my wife know I was staying over. I had planned to sleep on the couch but it was covered with piles of newspapers and bills, so I set up a blanket on the floor and tried to go to sleep. However, now that she was feeling a little better she insisted on puttering around the kitchen for over an hour. When I begged her to go to bed, she told me to fuck off and continued heating up sunflower seeds in her toaster oven. At least I was confident she was feeling better, but it was also frustrating. She went to bed around 3:30 and I finally passed out at 4.

I woke up at nine. I sat quietly and waited because I really wanted her to sleep. Finally at noon I was getting nervous and I tiptoed in to make sure she was breathing. She was snoring with vigor, so I wrote her a note and left. I saw her several times over the next few weeks. I also went to pick up her car for her. However, when she went to check in with her doctor at the retirement community, he told her that she couldn’t have it until she passed a driving test. They asked me to keep the car because she wasn’t allowed to have it without an updated driving test. This made her livid, but it was something of a relief to me because I was nervous that she might hurt someone. As she fought to get her car back, we found out her license had been expired for a couple of years. She scheduled a driving test, but I was doubtful that she would pass.

Just before Christmas, I tried to help her with her end of year donations. It was tough because she was confused and anxious and wanted to control the process, but she couldn’t really do it. So, it took about 10 minutes to write each check. It was good for us to do this process together because I had learned to be less reactive to her profound need for control, and that made her a little more trusting of me. This would prove to be helpful when things got more difficult with her health. Later, when I started to do more organizing in her place, I found boxes full of donation requests. It turned out that many of the organizations she supported sent out a new request each month. I imagine that my mom was sending out checks all the time, not remembering that she had done it.

Distance brings perspective. Looking back I can chart a long, slow, and somewhat steady decline. While it was happening, I knew it was going on on one level, but my attention was on helping her to “get better”, which increasingly became problematic as I wasn’t able to help make that happen without overwhelming expansion of energy. Even then, that effort didn’t lead to the kind of improvement I was hoping for.

Sometimes, during yoga this last year, strong feelings will arise. I’m not sure exactly what’s going on, but some of it has to do with gaining a broader perspective on how things unfolded. In those moments, I’ll have a sense of sadness, or empathy, or even frustration that has no real memory to it. Instead, it’s like a bubble of repression that gets dislodged through the process of seeking balance. Sometimes, it’s related to things that I didn’t want to see it at the time, like the steady sense of decline. With each recovery from a bout of depression, memory struggles, illness, or anxiety, I’d re-set to a sense of hope that the issues would abate, or that the anxiety would lessen. However, while there were periods of respite, the problems continued to pile up, like the mail on her couch.

As I said, I helped her with her end of year donations just before Christmas and then traveled to visit my in-laws over the Holiday. My brother came to visit her, and my sister and her family were around for my mom as well. She was feeling a little under the weather, but things were more stable than they had been in November and early December. Then came January. I got a call on January 5th from her retirement community letting me know that my mom was on the way to the emergency room in Hillsborough. They told me that she was having some breathing issues. I drove the 25 minutes to the ER only to find that she wasn’t there. As I tried to get information from the nurse at the front desk, I got a call from my mother. She was in an absolute panic, and I couldn’t understand what she was saying, but I surmised that she was probably at the other hospital in town which was only a mile from my house. She was crying for help, but she couldn’t seem to hear me. I was yelling that I was on my way as I ran to my car, but she continued to cry out for help and clearly couldn’t hear me. It was torturous to hear her cries but be unable to communicate with her. Eventually I double-lined my brother so that I didn’t have to suffer through the situation by myself. Honestly, I also wasn’t positive she would survive because she sounded terrible and I wanted him to have a chance to be with her too. My sister was also on the way to the hospital to meet me. While I hadn’t begun my year of yoga, I had been doing a fair amount of meditation. This practice helped me keep any sense of panic at bay. I reminded myself that fear wouldn’t be of any help, and I was able to stay in a place of acceptance. I remember parking, and making sure I knew where the car was. I was very conscious of staying present rather than retreating into my head.

When I got to the hospital, I quickly made my way to the emergency area she was in. I found her flailing about in a hospital bed, saying she needed to go to the bathroom. At that point, I had hung up my phone but I could see hers lying in the bed. There was a very exasperated aid with her who was trying to keep her in the bed because she really needed oxygen and she needed to calm down. The aid helped her go to the bathroom in a bed pan. She didn’t go very much, and it was clear that the anxiety was making her feel like she had to more than she actually had to. This pattern repeated for hours and it was not easy to see her in so much suffering.

After she had gone to the bathroom, I put a heavy hand on her shoulder and did what I could to calm her down. It helped, and I watched the monitor as her heart beat went from 145 down to a more reasonable 100 beats per minute. Her oxygen level was in the 80’s, so they had her on a tank, but she kept taking the tube from her nose because it made her uncomfortable. Yet the lack of oxygen also contributed to her sense of confusion so that made the problem worse as well. Over the course of an hour, we got her a little calmer and the chest x-rays quickly made it clear the the problem was severe pneumonia. Her lungs looked like a snow storm. Once they knew what was going on, they decided to send her back to the other hospital. This meant moving her, which I knew she would not want to deal with.

While I was waiting for the transport people, I got a text from my cousin. She let me know that she had just had a conversation with my 26-year-old daughter that I did not know about. I had been a sperm donor in the early 90’s and I had been working on a film about it, so it wasn’t a total surprise to me. Yet, it was still shocking, especially given the circumstances. They had matched on ancestry.com as cousins so it had been easy for my cousin to figure out who I was. I had written about my role a donor so she knew it wasn’t my brother. My daughter had reached out to my cousin first rather than go to me directly. I understood why, but didn’t have the capacity to speak right then, so I texted her to let I know I was glad to hear from her but that I would contact her shortly. My mom was by no means out of the woods, and it did not escape my notice that my mother was her grandmother.

My partners and I had been working on the film for a decade. Since I had not made any connection with any of my donor-conceived kids, I had followed a number of other stories. One friend told me the story of meeting her adoptive mother when she was 20. When she got to the house the first thing that happened was her biological grandmother handed her a shoe box with 20 birthday cards in it. She had held out hope that she would meet her granddaughter. Every time I hear, or tell, or type that story my eyes fill with tears. It so profoundly illustrates the power of family connection. As I sat there holding my mother’s hand I couldn’t stop thinking about that story. For me, this knowledge of my daughter’s existence was a great mitzvah, but it did create a disruption in my life that required attention. I wondered whether or not I should tell my mom. she had calmed down enough for me to put her in a wheel chair and take her to a bathroom. As I wheeled her back to her bed, I told her about the text I had received. She seemed pleased to hear it.

The next five days were some of the hardest and most intense of my life. My mom was very sick and it felt like I needed to keep a hand on her to keep her on this earth. As expected, she was very angry about having to move to the other hospital. I couldn’t go in the ambulance and when I arrived they wouldn’t let me in until she was settled. It was 3 AM before I essentially forced my way into her room because I realized that she wasn’t settling because they could not calm her down. A few minutes after I got in, she fell asleep. She slept fitfully, though, so I did keep a hand on her shoulder to help her sleep.

The next day, the doctors pulled nearly 3 quarts of fluid out of an area behind her lung. That and the antibiotics kicking in improved her breathing a great deal. She was still very sick, and the antibiotics gave her the runs. While the nurses were good, I ended up taking care of a lot of her needs because she could be very difficult to take care of.

Each night, she would have episodes of what they called ICU-induced dementia. It was kind of worrisome. She thought I was her husband and that was hard to deal with emotionally. She expressed a lot of love for her husband, but she also tried to kiss him, and that’s where I drew the line. I only got a couple of hours of sleep a night, but her health steadily improved. I went home to shower and nap each day and friends of hers would sit with her. On my first drive back to the hospital, I was able to connect with my daughter. That was a wild experience. From the moment we talked, I knew that despite the hurdles that existed, we’d find a way to forge a real and solid relationship.

Before this event, I had never experienced anyone who was as ill as my mother. In my effort to be “a good son,” I pushed myself a little bit too hard. While the effort seemed to help, it also left me severely depleted. It was weeks before I felt like I was getting back to normal. I learned that the next time we faced a similar situation, I would have to be careful to take care of myself so that I would be able to take care of her.

My new daughter, Holly, when I met her.

My older daughter, Fiona, the week before

My mom made it out of the hospital, but her health and memory were compromised. She was moved to the health care facility at her retirement community, and I went to visit each day. A few weeks later, she moved back into her cottage where she lived with complete independence. We started to think about the possibility of moving her to more supportive housing, but it wasn’t a conversation that she was willing to have. Around that time, I got to meet my daughter Holly on the day before my 50th birthday. It was amazing, but that, and turning 50, were a lot to orient myself to.

At the same time, Suki and I were rushing to finish a new documentary compiled from a series of short observational pieces we made at protests around a confederate statue in my hometown. We shot and shared these pieces online right after shooting them, and at some point realized that if we strung them together they would create a more complex narrative about what was going on in our public space at this time in history. We called the film “The Commons” because it all took place in the common space, and it was more about the interactions in that space than it was this particular fight. There were no interviews, and limited context because the focus was what took place in that space. We wanted the film to simply communicate what it felt like to be there. Before making this film, we had compiled 30 years of related protest work into a film called “Working In Protest,” and we saw this film as a continuation of that. Looking back through what we have observed creates more clarity than our experience in the moment (like this piece is attempting to do now). By weaving together many moments that are captured in a present way, we can create work that makes space for viewers to make their own sense of what’s going on.

A few days after my mom got out of the hospital, my brother came to visit her. As I drove him to the airport for his return, I heard a news report that the base of the statue at the center of our film was going to be removed. I had to rush back to film that. Seeing it float away gave the film a definitive ending. We had submitted our project to a few festivals and after we shot the ending, it got invited to a documentary film festival called True False. In early March, Suki and I showed the film there and it got a very positive response. However, at our 3rd screening, we were protested by student activists. The protest was led by a woman who was involved in another collaborative project about the statue. We knew of that film, and had donated a great deal of our footage for them to use. While we understood some of the concerns, and hoped to address them, the nature of their action made no space for conversation or discussion. In order to try to make some space for that discussion, we pulled the film from a dozen film festivals, but it was clear that there would be no discussion. It was a very difficult and alienating experience. The twin traumas of my mother’s health care crisis, and our “cancellation” left me adrift.

It was in this context that Caroline brought me to yoga, and yoga was there for me. It helped ground me, and it helped me navigate the rocky waters of my mother’s struggle for independence. That first class was tough. I went back to an easier, beginner class the following week. Each class began with some words about connecting to what was going on in our lives, and this helped me to step outside my situation, which often made me feel like I was in a whirlpool. Yoga helped me observe it with some perspective. A few days after our very difficult experience at the film festival, I told a friend that I was working on being grateful for the difficulty. I knew that it would help me grow. At the time, it was hard to imagine it, because the sense of dislocation and betrayal was so great. However, holding on to that understanding was helpful, and the practice of yoga continuously helped me to drive that point home. Yoga also helped me connect with my daughter Holly who was an avid student and teacher.

At first, I had a lot of trouble with getting into some of the poses. One of my legs is much weaker than the other, and that dissonance has not improved dramatically. However, my acceptance of it has been a big part of my practice. Noticing how I framed thoughts about it helped me shift that framing. Maybe that shift was one millimeter at a time, but it was still progress.

Today, May 5, is Suki’s birthday. Last year on her birthday, we had a small party that my mom attended. After her hospital stay, when she moved back into her cottage, she was trying desperately to get her driver’s license back, but she failed every test. Even though she was struggling with memory issues, she did not want to move to a more supportive living arrangement at her retirement community. My mother came to celebrate the birthday, and as usual, she was the life of it. However, she was a bit agitated and got a friend of ours to drive her home fairly early. The following Sunday, we had a Mother’s Day meal with her.

The day after that I met with her, her social worker, and doctor to discuss ways that we could help her address her anxiety. It was a tough meeting because she refused to recognize there was a problem, even though it was clear that the anxiety was now beginning to cause her to have small seizures. She was told by the psychiatrist she had finally agreed to see that she couldn’t return to the office. The doctor explained that when pressed to deal with anything emotionally difficult, my mother often had a small seizure where her head would drop forward and she would pass out momentarily. The psychiatrist didn’t feel like it was safe to see her. My mother refused to acknowledge that this happened. It’s hard to describe just how frustrating that was. When I told her this she said, “You see it your way, and I see it mine.” This was something she had said a lot to me over the years when I was trying to find some kind of resolution with her and she wanted to stop the discussion. Having the social worker and the doctor there, who could also clearly see that this problem needed to be addressed, made me feel a little bit less crazy, but also more emotional. Four days later, she had a seizure near the dining hall in her community. She fell backwards knocking her head on the ground.

I got a call from my sister who let me know that she had fallen and that they were observing her in the health center. Our mother did not want us to visit. My sister had been on her way to see her at the time and was told not to come. However, that night at around 10:30, my mother called me asking for the number of her cottage. She was lost and trying to find it. After getting her to agree to go back to the health center, I rushed over. She was confused and pacing in front of the building when I got there. She insisted on going to her place to get some things, but I was able to get her back upstairs. It turned out that she had snuck out of a locked floor. I was concerned, because the things she felt like she needed from her place had already been brought to her. However, it was midnight and I figured she had some kind of concussion and that it was best to let her rest. There was a a bandage on the back of her head, so I didn’t have a sense of the wound that was there. The next morning, I went to yoga early and called the health center afterwards to check in. I was told that she had gotten up, eaten, and gone back to sleep. Later, I was doing an errand and my wife went to visit. It was immediately clear that the situation was bad. My sister had arrived as well. She was a physician’s assistant, and they quickly decided she needed to get to the ER. Rather than call an ambulance, they got her in my wife’s car and I rushed to meet her at the hospital. By the time I got there, she was getting a cat scan. A short time later, it came up on the screen and we could easily see a massive bleed in the front of her brain. It appeared that she had fallen backwards, crushing her skull in the back which sent her brain sloshing forward on the front, which caused the bleed. When they prepared her for a move to the other hospital, it was made clear that she might not survive the transfer. My mom was very adamant that she wanted no interventions, so I gave my blessing and made my peace. I called my brother and sister to let them know.

She survived the ride. That night she stood up by her bed in the brain injury ICU and insisted that I take her back home. I had spent every night with her in the ICU in January, and knew that it had been too much. Now only four months later, the staff assured me that they had it under control, and I walked home. The couple of months of yoga I had been doing had already started to give me a little bit more presence of mind. I knew that in order to be there for her, I had to take care of myself. The next day it was difficult to hear that they had to restrain her after I left, but I also knew she wouldn’t have listened to me the night before. I was learning to make peace with accepting the things that I could not control. The next few days were very hard. Her brain was compromised by the fall, and while she had some days that were better than others, the recovery was difficult. Shortly before being released back to the health care center at her community, she was having some issues with swallowing. They decided to give her an endoscopy to check her throat. I was very against it because I knew from experience that she had terrible reactions to anesthesia. I went with her down to surgery and she was very out of it and uncomfortable. Eventually, I got the doctor to come in and showed them how out of it she was and that the procedure seemed like it was a very high risk for no clear reward. I got her back upstairs. The next day, she went back to the health care center.

Over the next five months, I spent a couple hours a day with her. My sister visited a great deal as well, and that allowed me to travel some with my family. For a long time, we pushed as hard as we could to find some way of helping her get “better”. We weren’t sure what that looked like, but we did all that we could. She got visits from the physical therapists daily and she had to have a 24-hour sitter, which she hated. For someone who wanted autonomy above all else, having a bed sitter was terrible. However, she was a huge fall risk and it was necessary. At one point, I joked that one of the aides should be called Yogi Berra because she caught her three times in one day. Still, she had more falls, and it took almost two months for the wound on the back of her head to stop bleeding.

Through it all, I went to yoga as often as I could. The practice helped me to lean into acceptance. There were many days that I visited at 4:30 and went to yoga at 7pm. Even when I didn’t go to class I tried to do some yoga every day.

When we want someone to get better, we do all that we can to make it happen. Eventually, I came to see that I simply had to meet her where she was. Some days she was fairly present. Then she might lose language for a week or two, or have a series of seizures. At some point the seizures would lessen and the language would come back, but the decline was also steady, and that was difficult to accept. She also had a lot of difficult anxiety behaviors like insisting that she pack everything up repeatedly because she was going somewhere, or she was terrified of missing her flight or the presentation that she had to give at a conference. In these moments, she could be quite mean. It wasn’t easy. However, it did get easier once I stopped trying to stop the action. I’d help pack, or unpack, or check my phone for the flight information. No amount of logic would change the drama. I just had to be on her stage.

At one point, we discussed hospice, but in a sense that meant giving up. In retrospect I wish we had chosen that route. It wouldn’t have meant giving up, but instead accepting the course that was unfolding. Very few people want to let their loved ones go. We often fight to help them come back. However, at some point, it was more clear than I wanted to admit that she wasn’t coming back. If I had to do it again, I would have let her go with less resistance. Still, no one was in control of my mother except for my mother.

In late August, I had to travel to Italy to print a book. My mother had been declining for some time, so I was nervous about going. A couple of days before I left, though, she rallied to an incredible degree. She walked several miles and she made up a song that was stunning in its wit. “All of your troubles will travel like bubbles, each one from a different store” she sang. It sounded like an old show tune and the lyrics were touching. The next day she was exhausted. As I left on the trip, I knew that she might not survive until I returned. On some level, I had made peace with that idea, and I talked about it with many of the people I met on my journey. At the same time, I was in denial of the fact that I was partly running away from that possible truth.

I got some reports from my wife and it was clear she was not doing well. My brother came to visit while I was gone and he was shocked at how poorly she was doing. The day before I was supposed to return from Israel, I woke up at 4 am and saw an email from my wife suggesting I come home right away. I immediately started my journey. I did a good job of staying calm on the lengthy flight from Tel Aviv to Newark. However, I had to rush to make my connecting flight, and on the trip from Newark to Raleigh/Durham, I felt like I was going to jump out of my skin. I was wildly uncomfortable and exhausted.

I met my cousin who arrived at the airport at almost the same time, and I told him that I needed to nap before going to see my mom. However, my wife arrived with our daughters. I had told her she should bring them to see her. I was resigned to the fact that we needed to go straight there and the exhaustion lifted.

As soon as we walked in, I knew that the end was very near. Her eyes were open but they were vacant. When my sister told her that I was there she turned her head so slightly that I did not notice. My children said their good byes. I called her other grandchildren so that they could say goodbye and we got my brother on the phone and we sat with her. I held her and waited. She passed away before midnight on my sister’s birthday, 9/9. At 10 am the following morning, I went to yoga. I sat next to a new person who asked me how I was doing. I told her that I was ok, but that I had been with my mother the night before as she had died. Yoga helped me to stay present in the moment. I knew I needed it, and I went on Thursday as well.

Over the next few months, yoga helped me weather the ups and downs of emotion that accompany the loss of a loved one. My relationship with my mother was complicated. She was a brilliant and charismatic woman. She was also someone who refused to deal with things that it might have behooved her to deal with. Still, yoga helped me ride those waves of emotion. Often, as I struggled to hold or move into a difficult pose, I feel emotions rising, and I let them rise. These are never clear thoughts, they are uncomfortable feelings. I’m still doing that, and they are still rising, passing.

I’m thinking about her a lot right now because this is the time that she was really struggling. I am too. We are safe, and in as comfortable of a situation as anyone can be during this pandemic. Still, the loss of connection and routine can be difficult. My lower back and my left leg have been bothering me. I miss the connection of going to yoga class, but I still try to practice a little bit every day, and I attend online classes a few times a week. I’m so grateful for yoga. I’m grateful for how it helped me weather the very difficult months of my mother’s decline. I’m grateful for how it has helped me navigate grief. It’s also helped me with acceptance. We still have had no chance to deal with the fallout from our film and the protest around it. In the end, it was clear that the issues were too fraught for people to have a reasonable discussion. So, like much of our work, it will be there when people are ready. It actually wasn’t so hard to accept that, but the whole situation was so confusing and fraught that it just took some time and effort to find that space to let it go.

Dana Anne Galinsky-Malaguti

Posted at 13:14h, 07 MayWell I just wore a 99 minute response lol and I keep getting error error error hmmmm. Love from your Big Sister Dana. Maybe you might get this one lol