13 Feb Burnt

Last night I spent a little time going over a grant application for film funding. Years ago, I gave up on applying for grants because we never got them- literally- in our first ten years of applying, we got none. The one positive thing about the process is that it does force one to do the work of articulating what the film is about, and that can be useful. However, we often need funding for projects that have not taken full shape yet so that effort is counterproductive, forcing us to build a false narrative in order to seek support. Further, the things that funders are looking for inevitably affect the way we not only talk about the work, but also how we construct it.

Sitting down to look through the grant application reminded me why I had previously given up. As I filled it out, I was aware of feeling both anxious and physically uncomfortable. I listened to that feeling and realized that it felt fruitless for me to work on it. I quickly dashed off a Facebook post about those thoughts and it resonated with a lot of people. As I wrote it, I was aware of just how fraught it can be to “complain” about lack of support. I was very conscious of not complaining, but instead, offering context for why it didn’t make sense for me to do it. On one level we need funding, and on another, we all have a need to feel accepted; to have our work embraced. However, I rarely feel that my filmmaking goals align with that of funders – whether they are grant funders, TV funders, or public TV funders – so I’m often asking for approval from those who aren’t going to see value in the work. Frankly, it didn’t feel “safe” to articulate all that, but it felt necessary. In the end, I was simply stating that it didn’t make sense to seek approval from people who were never going to approve of me. I’m writing this to explore those ideas further.

Split_Screen, "Lost in Spain" from rumur on Vimeo.

Many of us learn early in life that complaining is something to avoid. Later in life, we are taught to “fake it till we make it”. I picked this up in high school and learned to project confidence even when I felt anxious and shy. It worked to some degree, and I made more friends and found more acceptance; but it was also exhausting. When we present a false self, it takes a lot of energy and effort to keep it up. In the end, this effort led me to feel more anxious which conversely made it even more stressful to appear outwardly relaxed. When I got to college I had the opportunity to be a completely new person. I think on some level I also became a slightly less present person. By the time I was a junior in college I had become more comfortable with myself but also a bit more stressed. That year I started a band with two friends, and it would be the center of my life for the next decade.

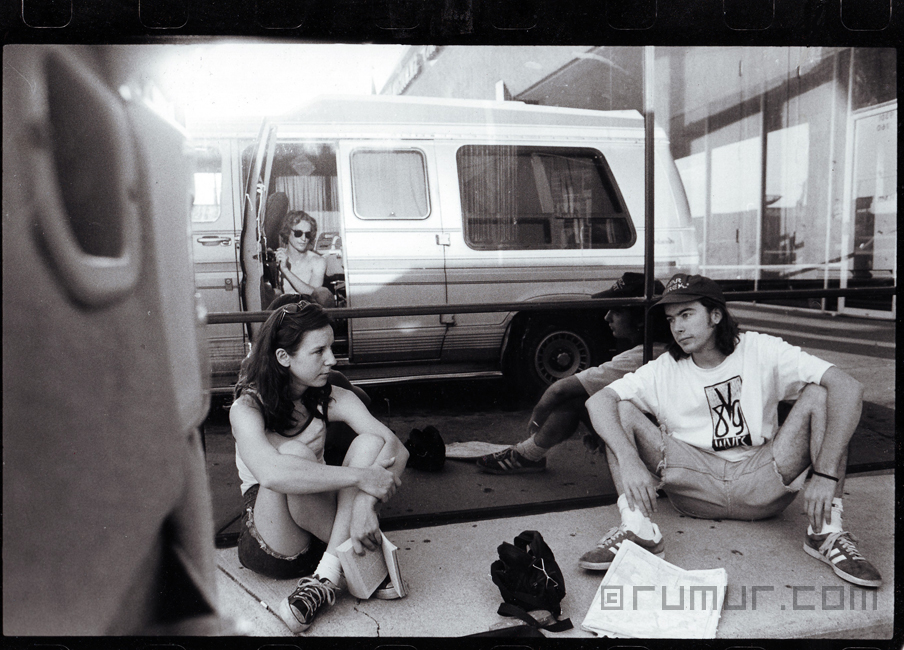

Being in a band provided an outlet for me to both release some of that stress and also find a space where I could let go of that false confidence and accept myself a bit more. Through my band, I found lifetime friends and a path towards making art. My band was part of a deeply DIY culture that eschewed systems in favor of direct communication. We made our own singles, booked our own tours, created our own media (fanzines), and through that effort we connected with people who supported us, and whom we supported. On some levels, there were gatekeepers who controlled access to the audience – i.e. record labels or club bookers – but in general, we were skipping over a lot of that by making efforts to make direct connections. After about 5 years of having a life that revolved around being in a band, and documenting that world through images, I met my future wife Suki through her roommate. Suki was in film school and I talked her into dropping out and making a film about the music world instead. We’ve been working together ever since.

don’t let the quotes fool you.

Suki and I made our first two films with very few resources and it was exhausting, especially because they were shot on film which required a crew and hard expenses like negative film, processing, and sound mixing. I don’t recall applying for any grants for them because we didn’t even know about grants. These two films were much more a product of music culture than they were of film culture, so I wasn’t really prepared for how to interact with the film system once they were done. Suki knew a bit more than I, but she was still very much a student. She had worked at Sundance, so she knew a bit about film festivals. However, she didn’t think that she needed to use her connections there so she didn’t. Applying to festivals gave us our first insight into having to deal with gatekeepers in order to reach an audience. We filled out tons of forms and sent them out with a check and a VHS of “Half-Cocked”, only to get rejected from our first 35 festival applications. Frankly, it was kind of shocking to find that no one in that world could see any value in our labor of love. Ironically, a Variety critic had come to our cast and crew screening and unbeknownst to us he had written a stunningly positive review, yet it had no impact in terms of the film world, because we were so outside of that film world.

Half-Cocked Trailer – 2018 restoration from rumur on Vimeo.

Since it was a music scene film, we simply loaded a film projector into a van and took it to rock clubs. We found it to be extremely gratifying to get it to the audience that wanted to see it. It also got a little tiring, but we were young- and resilient. One way we got the film made was by simply telling everyone we were doing it. In some sense, it was kind of faking it till we made it- but I wasn’t faking it. I knew I was going to make it, and I had enough ignorance of the process to have no doubt. Still, when you believe in something deeply as I did in this project, and the people who hold power reject it completely, it’s fucking hard to take. In the end, it didn’t make me doubt myself as much as doubt the validity of systems even more than I already did.

After we finished the film, I kept playing in my band and we kept traveling with “Half-Cocked” for a while. On one trip with my band in Spain, the tour promoter suggested bringing the film there. Suki was not excited about the prospect of watching the film over and over again so I concocted an idea of making a new film while we traveled with it. Yeah – you guessed it! It was a total nightmare, but we got it shot. “Radiation” is a more “professional looking” film than “Half-Cocked,” but I don’t think it had the artistic vision that Half-Cocked did. However, “Radiation” did get support from the film festival system. After being invited to Sundance, we got invited to dozens of other festivals. We even got an offer of distribution from Palm Pictures. However, that offer was dependent on an important theater in NY agreeing to show it – a theater that Suki had worked at in concessions while writing “Half-Cocked.” They refused, and like that, distribution disappeared and pretty much no one ever saw it outside of a festival. People outside of film have no idea just how much power a few gatekeepers have over what makes it over the transom. Since it was on 35mm, and video projection wasn’t the option it is now, there was no way for us to deliver it to audiences ourselves.

Still, the festival success seemed to bode well for a new project, but lack of commercial success put something of a damper on that. Frankly, we were just completely worn down. I quit being in a band and took a “real” job (kind of), so that we could get a mortgage to buy a house. It was even more soul-crushing than I had imagined. For the previous 10 years, I had lived as cheaply as possible, and worked as little as possible, in order to carve out space to be creative. It worked: I was wildly creative and generally somewhat happy. When I got the job, which started out as “consulting” but quickly turned into an expectation that I show up in the office, I found myself feeling decreasingly creative. After a year, when the company fell apart, and I was already in the house, I had more time to make work again, but found it hard to find the spark that had always been there.

Horns and Halos from rumur on Vimeo.

While I was working at the job, we had gotten a video camera and fell into working on a documentary about a punk rock publisher who was re-publishing a discredited bio of Bush. Because I was at the office, Suki put in more time shooting and editing the film until finally my job imploded, and I had time to work on it. As with our first narrative film, I didn’t really know how difficult it was to make a documentary, which made it both less and more possible to make. We didn’t have as many “hard” expenses, but we needed resources to support ourselves while we did the work. This was when we started to apply for grants in earnest. Again, we didn’t need much more than time. We had an editing system from our previous film and a 36gig drive to boot (it had cost us five grand). Around this time, David Beilinson offered to help us out and he had access to a beta deck from his job which was a great asset. We applied for about a dozen grants, but found no support. While that film wasn’t virulently anti-Bush, we were hampered by the fact that our final shoot day was Sept 10, 2001. After that, no one wanted to look at anything even vaguely unpatriotic. Meanwhile, Suki was 8 and a half months pregnant when we did the final output and by the time I came home at 5am from returning the “borrowed” beta deck, her water had broken and our premiere was set for the following day. She missed the NY Premiere.

It took a year before people began to question Bush and his wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and at that point we found some success with the doc. “Horns and Halos” was invited to the Toronto FF almost 9 months after we first showed it. It also got short-listed for the Oscar, and sold to TV in 5 countries. That floated us for a while as we worked on our next projects. It’s also when we went into full on beast mode in terms of grant-writing. We wrote like trained monkeys for a couple of years, applying for dozens of grants for our documentaries “Battle for Brooklyn,” “All The Rage,” and “The Broken Angel”. We applied for Sundance, Guggenheim, Tribeca, Jerome Foundation, Creative Capital, all multiple times, and all of them were rejected.

Broken_Angel_Doc (extended trailer) from rumur on Vimeo.

With no funding, we ended up giving up on several films. “All The Rage” went on hiatus for 5 years – until the stress of dealing with “Battle for Brooklyn” sent me crashing to the floor with back pain and we decided to revive that doc, which was about dealing with mind body pain related to stress. Despite three solid years of shooting, “The Broken Angel Project” exists only as a trailer and as fractured elements on a drive – we just never had the resources to work on it and we knew it wasn’t a project anyone would pay for until it was done. It was further complicated by the fact that it’s about a litigious artist who decided he didn’t want us to make it after we had shot for 3 years.

While we had some success with “Horns and Halos,” we kind of crashed out of the film festival world around that point. Our follow up, “Code 33“, a doc about a sketch artist and a search for a serial rapist, got invited to a few “big” festivals like SXSW, but it wasn’t really “of the moment” and no distributors knew what to do with it. It was particularly frustrating because the reviews were over the top in their praise for the film (Variety, Hollywood Reporter, E-Film critic, etc). Eventually it was turned into a TV film that paid well, and floated us again through the next projects, but turning it into a TV film watered down the work. Having given up on grant funding, we spent a number of years pitching TV projects, but that went nowhere. In general, our films weren’t “social-issue enough” to get grants and we weren’t commercial-minded enough to get TV money, so we ended up spinning our wheels. The more we worked outside of both of those worlds, the less connected we became.

Our experience with “Battle for Brooklyn” was very similar to that of “Horns and Halos.” Both films experienced great resistance at first, but eventually they got critical praise- and both were short-listed for the Oscar. However, the stress of that whiplash effect was enormous, and both times I found myself crippled with back pain due to the frustration. The first time after “Horns and Halos” I ended up in Dr John Sarno’s office, and that sparked the production of a film about him. When we couldn’t figure out how to fund it or make it, we stalled out. However, 6 years later, when the pain came roaring back when no one would show “Battle for Brooklyn,” I hit the floor again with a resounding and painful thud. As I recovered, I realized I had to become the character that we needed to tell that story of pain. As that year ground on, the Occupy movement took off, and suddenly people understood our protest film in a new light. Eventually, that led to us getting our first and only grant, a Guggenheim in 2012.

However, the small burst of interest in “Battle for Brooklyn” didn’t lead to any other grants or more acceptance from film festivals. It also didn’t lead to distribution. The only offer we got was from a start up that promised to put it on screen in 12 cities but did absolutely nothing. Our next doc, “Who Took Johnny”, which was funded by doing a shorter version for TV first, had almost no success with festivals. It premiered at Slamdance, but it took us a full 16 months to get a real review. By that point, it was “old” and no one cared, so despite the very commercial crime nature of the story, we ended up getting it on Netflix ourselves with the help of a sales agent. It became something of a sensation on Netflix. Still, because it didn’t play the festivals and no one in the “film world” wrote about it, most film people never heard of it. The downside of that has less to do with ego than the fact that it didn’t help us move other projects forward.

One of the dangers of detailing some of these foibles and pratfalls is that it inevitably sounds like complaining, bitching, and moaning. In fact, what I’m trying to do is tease out the connections between the work and how difficult it can be to make the films that we want to make, knowing that it isn’t very easy to fund them- or get them to an audience. That this difficulty puts pressure on filmmakers to make work that conforms to expectations rather than challenges them. Further, that the funding process then shifts the expectations of the programmers – and when those are linked, that changes the whole system in profound ways. When Sundance and TriBeCa barreled into social issue – everything became social issue- and the films that get in are the ones they track and support first through the funding process. These films were super-colonialist with “social issue”- so that has been turned into a de-colonize docs movement – which is useful and important – but also becomes the thing the system will barrel into head-on without fully understanding how that machine affects everything… I just wanna make art –

By the time we hit the festival circuit with “Battle for Brooklyn” in 2011, an explosion of strong content had begun to throttle the distribution pipes. Despite our history, and our connections, we literally found it almost impossible to even get film festivals to watch our films- because they were being inundated with high quality films. Last year I was a screener for the Big Sky Film Festival and the quality was so high that out of 100 films I viewed, at least 50 of the absolutely deserved to find an audience, and only 10-20 percent were just not strong. My point is, that I understand why it’s so hard to find support, or get anyone to make time to watch our films. Programmers and distributors become so overwhelmed they often limit themselves to watching things that have already been anointed by others. With 75 docs premiering at Sundance, SXSW, True False, and Tribeca- I can understand why they have trouble viewing our film. So the competition for important eyeballs becomes increasingly fierce.

As we worked on “All The Rage,” our Dr. Sarno documentary, we applied for a few grants and we pitched the film at the Big Sky pitch session- twice, but we found no outside support. On one of those trips, I was in a van to the pitch session when one of the funders apologized for having the extra “How will your film lead to changes” section. I could not stop myself from pointing out that not only did every grant ask for that by then- BUT that it was also like asking for a propaganda plan in advance. That didn’t go over very well and she pointed out that all of the films they fund shine a light on vitally important issues. “I have no doubt that this is true, but I also think That Goebbels felt the same way,” I said even though I realized I was killing any chance of getting support. My pitch experience was brutal.

Kickstarter had begun as we finished “Battle for Brooklyn,” and we were one of the first films to raise 25k on the platform. With “All The Rage,” we were able to raise about 90k, which helped get us over the finish line without going broke. “All The Rage” is our most complex, yet worst-reviewed, film we’ve made. Thankfully, all of the emotional work that we did to make the film made it possible for me to avoid the soul crush that hit me after “Horns” and “Battle.” The good news is that “All The Rage” literally changes people’s lives. Yet, it’s almost impossible for us to get it to people. That’s pretty hard to struggle with. However, each day I do a little more pushing and promoting and each day it gets watched by an average of 20 people.

The post I wrote yesterday sparked a lot of discussion, as well as a lot of private messages saying essentially, “thanks for daring to say what I feel.” None of us have a “right” to funding to make our films. However, I do think we have the right to express frustration about how systems have a tendency to reject things that don’t cede power to those systems. The truth is, I’m lucky. I have lots of privilege. I have friends and family that support me, and family that help me get through the difficult dry spells. I’ve been able to find work around. I just make what I’m gonna make and I try not to give too much of a shit about the people who get in the way. I’m also all for the decolonization of documentary. I’m gonna help other people make films but I’m also gonna keep making my own work- cause that’s what I do.

No Comments