13 Dec Capture it Now. Figure it out Later

A couple of years ago, I wrote “A Letter to Young Photographers“. This post is meant to build on that idea, but with a more expansive focus. In the last few days, I’ve been pulled back to my archives of older work because a friend, Bill Siegel, passed away suddenly. He was a great filmmaker (“The Weather Underground” and “The Trials of Muhammad Ali”) and a beloved friend to many. We met in 2002 when we were both at the Flaherty Film Seminar. His passing made me think about my own life, and searching for the above image opened a Pandora’s box of my past work. That search has led me to meditate a bit on where I am and where I am going. I’ve spent the past few years trying to organize the work that I have done, and make some sense of it. I’m in the midst of writing something about all of our films, and I have also been thinking about my photo work. In addition, some of my band’s records were re-released, so I have been thinking about how all of my music, photos, and films connect- and in some sense form a collective body of work. I’ve been trying to conceptualize a book about it all, but like much of what I do, it keeps expanding. My working title is “Lessons Learned: 30 Years of Making Work.” The idea is to look back, reflect on the work, and try to frame it around some of the lessons I’ve learned both from the process, as well as reflect on the process itself. I’m a terrible editor, so thankfully Suki keeps me in check. For the time being, I’m gonna let it expand like frozen croissants set out to rise overnight. In any case, Bill’s passing started me thinking more about past work and some of the lessons to be learned from it, so I’ll spit those out and hope Suki can help make sense of it.

I’m not a teacher, though I sometimes pretend to be. At the time that I went to college, and took a couple of photo classes, schools were mostly filled with older white male teachers. However, I was lucky enough to have women teachers for all three of my photo classes: Lorie Novak, Sylvia Plachy, and the woman who set me on the road to shoot Malls Across America whose name I can’t recall. Since I wasn’t a photo student, I had to get permission to take the classes and I hit the jackpot with Lorie, who was just a fantastic teacher. While Sylvia, and the man she taught the class with, clearly had more seniority and authority, I got the least from that class. I was interested in photography, and saw teaching as a possible pathway towards staying fed, but it was clear that teaching jobs in major cities were highly competitive – and I was not – so I didn’t really see that as a possibility.

Since I took relatively few photography classes, my main teachers were photo books. Back then, the internet was not a part of our lives. I didn’t get email til a year or two after college, so access to work was limited to books, and the books themselves were hard to find. The store A Photographer’s Place, however, was a treasure trove. Yesterday, I saw a post from the photographer Nick Walpington, looking back at his work. So many of the comments were from people who discovered his images in libraries, and it awakened their interest in photography. I found Nick’s book “Living Room” at A Photographer’s Place and it had that kind of impact on me. The images were well- crafted, but they were also intensely intimate and personal. He was a young man when he made the work, and it launched his career. On the post he had this to say;

Whatever you release into the world art wise you no longer own, it belongs to whoever views it and whatever they think or interpret about the work is as valid as your original intention . I love this democracy. But If you are lucky enough to make art over a lifetime the harder it becomes to connect with your early work as you are mentally further and further away from the art you made at the beginning of your career. I am lucky enough to find myself in this position as I was a young starter. I am as pragmatic about this as I can be. I am still excited as I go to bed about what I will wake up and make tomorrow, all I’ve ever done is make art. But sometimes I hate the work I made when I was young. Not that this should stop you liking it. Just remember I am not old yet and my best work is yet to come. So here is a picture as therapy to embrace the past.

I have had a somewhat opposite experience, which is partly what this post is about. As I made work that, for the most part, did not get released into the world in a widespread way, I don’t have the same reaction to it that Nick does. While I have put out some records, movies, and photo books they, have not become a part of the dialogue in the way that Nick’s work has. Since my work was largely unseen, it never came to define my sense of myself. While on some level we all want “success,” not having it can be freeing. When there’s no substantive, career-defining success, there’s a lot less pressure on subsequent work to conform to some idea of what it should be. The comprehensive gaze affects the image and the maker.

The other day, I went by my friend Lindsey’s art show. She had piles and piles of prints on a table that she was basically giving away. A lot of what Lindsay shoots reminds me of my own work (especially the color photos I shot in the mid-90’s while touring a lot), so I’m inclined to see value in it. The work is simple, sometimes silly, but also profound. Her work has a lot to do with noticing things that other people take for granted, and finding not only beauty but appreciation for things that often go unseen. Even though it’s an explosion of noticing, there’s a clear sense of vision to it. At her event, we talked about the fact that she’s been trying to figure out a book for a long time, but is clearly overwhelmed by the task. This brings me to my first lesson learned from experience: As I tried to tell her, at some point you just have to make the book/film/record and recognize that it’s not going to be everything- that it will fail on some level. However, by putting it into the world you create the dialogue that Nick Walpington speaks of. While I haven’t had Nick’s success, I have become increasingly committed to putting my work into the world.

Slow Motion Time Lapse from rumur on Vimeo.

When my friend Ruddy Roye introduced me to Instagram one day in late 2011, I had just gotten an iPhone and was starting to use it to make images. That weekend, I went to San Francisco and posted probably 300 images. Now, I have 18 thousand up. I’m told by many people not to post so much, or to use hashtags to gain more followers. Now and then, I try to add hashtags, but it rarely makes sense for what I’m doing. I’m just “noticing,” and for the most part that doesn’t fit with what people are looking for. For me, the photos are an extension of a lager connection between my life and my work. My documentation has less to do with making “stunning images” than with capturing a moment that will not be there again. In the present, the image may seem mundane, but the work gathers meaning over time. Earlier this week when I went to grab the image of Bill, I also found an image of Garrett Scott, who passed away only a few years after that Flaherty Seminar. Both of those images now have much more meaning than they did when they were taken.

In college, I was more interested in music than I was in photography, but I interacted with both in similar ways. Just as I cruised the record store, Sounds, for albums, picking through the pricey ones to learn the history, and buying the cut outs for affordability, I worked my way through the books in A Photographer’s Place and picked over the cut out table in front to bring home the affordable books. I believe I took home Walpington’s “Living Room”, but my books are in Brooklyn and I am in North Carolina. In any case, I spent as much time listening to records and perusing the books as I did going to class. I also began to go to rock shows more than class. At the time, though, books were my only way to access images. There were photo galleries showing work, but I wasn’t hooked into that culture, so for me books were my way in.

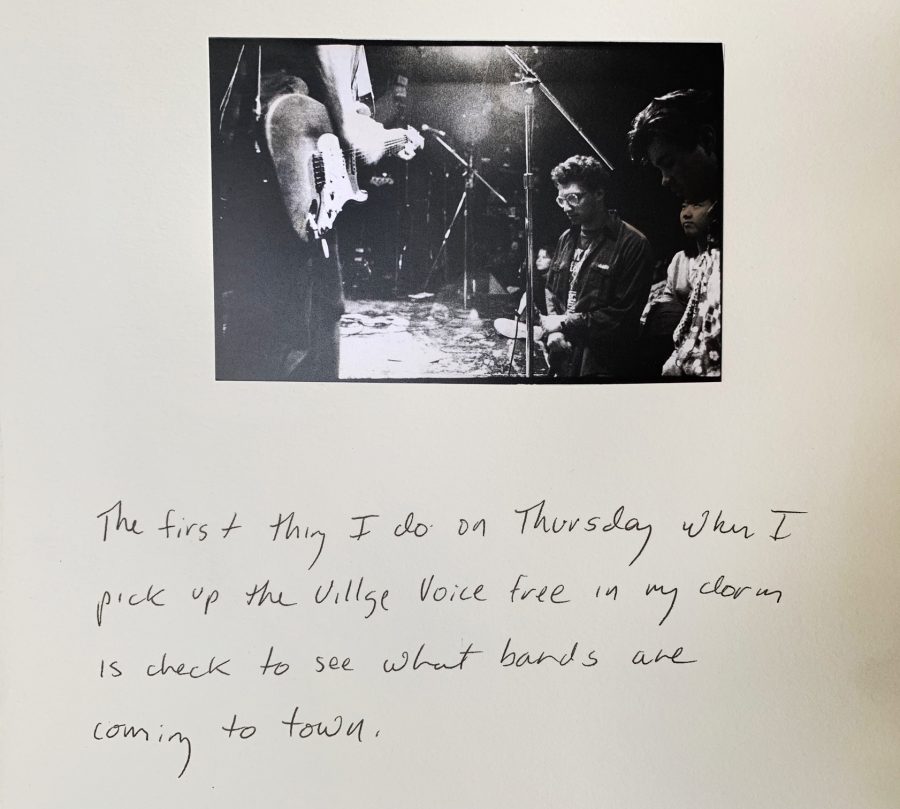

While I became increasingly obsessed with music, I didn’t start to take pictures at shows for a few years. I credit Mike McGonigal with getting me to start shooting more because he used a couple of my band photos in his magazine Chemical Imbalance. I incrementally began to drag my camera to shows, even at shows that I never took a photo at. I had a friend, Gail Horio, who worked at the NYU radio station, and she tipped me off to live shows that I had to see. I believe that’s how I ended up at a Laughing Hyenas show at the Pyramid in ’89. The Honeymoon Killers played first, and they were interesting, but when the Hyenas came on, I was floored. They were tight, pulsing, and scary. During the song “Gabriel,” the singer, John Brannon, smashed the microphone into his face and blood mixed with sweat to make a mess. It was by far the most powerful show I’d seen. I hadn’t brought a camera. A few months later, I saw Nirvana at the same venue, again at Gail’s suggestion. There weren’t very many people there, but those who were – Sonic Youth, Iggy Pop, etc. – were important. It was the last show of their Bleach tour, so probably their last with Chad Channing as drummer. They only made it through a few songs before Kurt stopped everything to show Kris how to play the bass line of Love Buzz properly. Kris still didn’t get it, so Kurt pushed his amp off the stage and then destroyed the drums with his guitar- which also destroyed his guitar. It was a pretty powerful event but it didn’t come close to the Hyenas. Again, I hadn’t brought my camera. After that, I brought my camera. I was thinking about a lot of this because there was an awesome oral history of they Hyenas in The Detroit Metro Times this week.

Most meditation is focused on being present in this moment right now. The goal is to recognize that the past and the future are all projection, and that only this moment is real. I have been doing a good deal of meditation and I get that, but still see that sometimes looking back is a way to connect more powerfully with the present. Often, as an artist, I can lose my mooring in the present moment by being so focused on capturing it in images. There are many times when I have recognized this and decided not to shoot. On 9/11 I grabbed my camera on the way out the door, but then put it back down because I had a sense that I needed to be present that day. Sometimes, though, in the more mundane moments, capturing quiet moments allow us to be focused, and those moments have a different meaning in the future. Seeing events in the past – with their slightly different details, fashions, and design elements – wake us up to the things we stop seeing in the present. Picking up a camera can help us to be more aware, more radically present, even as it can take us out of the moment. Reading the Hyenas article made me think a lot about how powerful documentation is.

While Nick Walpington is looking back with some chagrin, I have been pulling old images from the drives and sharing them. This image of Pavement came from a shoot I did for a magazine cover for Puncture Magazine. At the time, I was doing a lot of work for small magazine that could barely cover the cost of my expenses. I was also making promo photos for bands that had no money. I almost never felt exploited by these situations because they gave me a reason to make work – I needed that reason and was glad to be a part of something. Those magazines and bands were not profiting from my work. They were benefiting, as was I. Yesterday, Bryan Wendorf who runs the Chicago Underground Film Festival posted a complaint about “generic filmmakers” asking for fee waivers at an ever increasing rate. The comments from younger filmmakers were vicious. I too hate to pay fees, especially at my advanced age, and understand why they find it to be exploitative as well. At the same time, I understood what Bryan was saying: that people who had no understanding of what CUFF was about had no business asking for a waiver without trying to first figure out if it even made sense for them to apply to the festival. By their very nature, underground festivals don’t attract sponsorship or foundation support. CUFF has shown every one of our feature films. While they have never paid us a screening fee, neither has more than a handful out of hundreds of festivals we’ve played at. They have made an effort to help us cover travel expenses and find us a place to stay, and they have bent over backwards to support our work. This is not to say that a large swath of the festival circuit shouldn’t be viewed as exploitative. The discussion prompted me to think more deeply about how and why I make work. It was kind of depressing to see so many people attack Bryan for his offhand comment of frustration. Bryan has been working for more than 25 years to make a space for filmmakers to connect and grow. As with the photos I did for free for magazines, I understand that we both benefit from working together. Neither of us are really benefiting financially, but we are building something together.

Walpington may have moved on from his past work, but I am just starting to harvest much of mine. Going back through that work has less to do with nostalgia for me than learning about – and trying to communicate an awareness of – being present. Sometimes capturing images and ideas is just the start of a long process. Sometimes the work only makes sense in the future, especially in what it can help reveal about the present.

Terence J. Elliott Tolkin

Posted at 08:28h, 20 DecemberHey, anybody ever tell you that you care too much, Michael?

#metoo

Go ahead and tray and stop it.

Constant worry and fear of failure are what keeps us creating.

Everything’s a fukin trade off

I LOVE the

idea of you warming back up to your photography

I like paying compliments to people who deserve them.

People LIKE to look into your camera, Michael.

that’s over half the battle.

Then there’s…..The Meadow……#thatfukinmeadow.