30 Sep If Stress is the Real Problem, Ignoring it is Dangerous

This video was made when my daughter was 3. I’m not sure if we were the ones teaching her about responsibility, or if it was her day care, but as you can see, she’s never been too happy about the idea of taking responsibility for her actions. Who can blame her though. Very few of us want to feel responsible, especially if it for someone’s suffering, even our own. It’s a messy concept.

About a year ago I wrote a post about my amazing photo teacher from college, her problem with migraines, and how understanding the emotional connection between her emotions and those migraines might help. I don’t know if she ever read it, but she did come to see “All The Rage” when it played in NY. I’m happy to say she loved it- which was meaningful to hear from a teacher who had a profound influence on my life and work. While the film helped her to make the connection between her emotions and her migraines, she continued to express frustration about the fact that migraines aren’t taken as seriously because they are seen as a “women’s problem” and/or that women are “more sensitive” to the symptoms- which then means that their pain is often disregarded. I agree that these are serious issues that need to be addressed. In fact, I think that the way in which women are treated is central to the problem. However, I believe that the reason more women have migraines than men is likely due less to bio-physical/genetic issues than it is to cultural/social ones.

I am not making the argument that having migraines is the women’s fault. Instead, I would argue it is a problem of our social structure which puts women at a direct disadvantage to men in most every aspect of civic life, and that this is unconsciously enraging. Those feelings get held in, but they are still there, and it takes great effort to keep them from rising to the surface. When we don’t recognize this unconscious rage, or have any sense of how it affects our health, we can’t do anything about it. Even when we do recognize it, it is difficult to address. In fact, for many people the unconscious rage is so difficult to address that it seems ridiculous to suggest it exists, or affects us. In fact, for many people the suggestion that stress, chronic anxiety, and the repression of emotions could be the major factor causing auto immune or pain issues is consciously enraging. Many people have let me know that my suggestion that emotions could be the cause of their pain enrages them.

However, recognizing that a mind body interaction could be the cause of the problem doesn’t mean that anyone suffering from these issues are therefore “responsible” for their suffering. Instead, understanding that unconscious emotions might drive this problem gives us the ability to respond to the situation. To argue that there is nothing we can do ourselves, and instead handing over all responsibility to a medical system that doesn’t understand what is going on, doesn’t appear to be a good solution. The cost of treating just chronic pain has ballooned exponentially over the past two decades and it vacuums up more resources than most other health care issues combined. We’ve seen the amount that Americans spend dealing with chronic pain increase from $58 billion in 1986 to over $636 Billion in 2012 (meaning it has to be over a trillion now). Dr Gabor Maté, author of “When the Body Says No” spoke to us about this idea that repression is a driver of illness in an interview that we did for “All The Rage“.

When we look at the literature concerning health issues that have “no known etiology”, we find that many of these involve both an auto-immune response and/or pain. We also find that these illnesses generally affect more women than men. When looking at this situation purely from a bio-physical perspective, it is difficult to understand why that might be the case. Articles which examine the causes for these issues are mostly speculative because even with all of our scientific know-how we have not been able to figure out why people have them at all. What if it is because we are ignoring the profound role of stress and emotional repression as a causative factor? In almost every case, the literature will cite stress as a risk factor, but not mention it as a cause. However, when we look at the reality of living with a chronic stress response that is largely unconscious, we can see that it’s like being stuck -at a stoplight with our foot on the brake and the gas at the same time. We are aware that we aren’t moving but we might not notice that our foot is on the gas, and that this is wasting resources and damaging the machine. When we are locked in this pattern of response we use up our physical and emotional resources without getting anywhere. Eventually, the car will conk out.

Zooming out and looking at the situation from a more complex bio-psycho-social perspective – examining both our emotional response to the world as well as our relative position in society vis-a-vis gender, race and class – we can see possible connections between these factors and pain/illness. It is a well established fact that women are paid less than men and given fewer positions of power within government and the workplace. These facts establish that women are generally at a disadvantage and have far power in business, higher education, administration, and government. This kind of disadvantage amplifies one’s inability to challenge the systems that they are a part of. Those with less power are compelled to be more repressive of their emotions and thoughts than those who have power. These issues become increasingly pronounced when one’s career and livelihood depends on the approval of people on the ladder above them. As Upton Sinclair wrote “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.” In order to keep their job, or position, people have to become willfully blind to things that might be obvious to outsiders.

Again, this doesn’t mean that we should consider the person who is faced with this unjust situation, and who suffers from pain or related illnesses, as being “responsible” for their own suffering. In fact, for the most part, they often don’t even have a conscious understanding that this kind of emotional repression is involved. Further, if this idea is suggested to them, they often reject the idea angrily. Often times, this is because they take this to mean that they are being told that their illness is “all in their head.”

Ashok Gupta, who developed an understanding of how this process affects the body as he worked to cure himself of chronic fatigue, has a great way of articulating what is going on. He describes the brain and the nervous system as the hardware and our emotional response as the software. When the software gets “corrupted,” then the hardware breaks down. When our emotional patterns of response to the world involve unconscious anxiety that affects us physically, then the hardware doesn’t function properly.

Our amygdala is the almond-sized, “caveman” part of our brain that instigates our fight or flight response. It reacts to perceived threats largely based on what the frontal cortex (our thinking brain) tells it to do. While the frontal cortex can differentiate between a physical threat and an emotional one, the amygdala does not. It relies on the frontal cortex to let it know that the body doesn’t need to be physiologically ready to attack (flushing the system with adrenalin, etc.) just because we’ve been given a pop quiz in class, or a work assignment that might decide the fate of our career. In our modern day, this process sometimes gets confused.

Gupta describes a scenario in which we almost get hit by a bus because we aren’t paying attention as we step off a curb. The amygdala might initiate the fight or flight response – in order to throw us back out of harm’s way – before we are consciously aware of what’s going on. Our gut often knows before our frontal cortex does, and it responds for us. It is at this point that a critical communication occurs between the frontal cortex and the amygdala. If the communication between the frontal cortex and the amygdala gets immediately short-handed, which many neurological processes in our body do, the amygdala may assume that buses in themselves are scary. From that moment on, the amygdala will flood the body with stress hormones to prepare for fight or flight whenever it sees a bus. It begins to do this without wasting the resources of checking in with the frontal cortex because the original interaction writes the code- establishing a pattern of behavior. This behavior quickly becomes unconscious.

When the body is primed to be on hyper alert for all kinds of threats in our world, the spiral of heightened anxiety takes hold. Say we walk down the street and see a person who has a gun. If he smiles and waves, we can see that he is not a threat, let him pass and stand down, shake it off and go on our way. If we fail to do that, and stay in a state of unconscious hyper-vigilance, this can start a cycle of unconscious anxiety and fear. Soon that level of anxiety becomes a new normal and we don’t even know what we’re anxious about half the time, or really feel anxious at all. I remember finding myself in this state halfway through my freshman year of college. I was overwhelmed, disorganized, and seriously lacking sleep. I would find myself trying to figure out why I was so anxious in the belief that if I could just figure out what class or paper I might be forgetting, I could get the anxiety to abate.

In looking back at the situation in we almost got hit by a bus, if instead of consciously thinking that buses are scary, or even failing to acknowledge that they aren’t necessarily dangerous, we tell our amygdala, “not paying attention is dangerous. I must be more mindful when I am in a crowded space,” then the brain doesn’t see the bus as a threat and it does not flood the body with stress hormones each time it sees one. Unfortunately, we know that when the body is constantly flooded with these hormones, our immune system is compromised. It can get confused about what kind of threat it is preparing for. Like my process of searching my brain for the thing I might need to do for school, the immune cells might start to look for things in the body to attack, and these attacks bring on the symptoms we associate with an auto immune response.

The good news is that awareness of what is going on gives us the opportunity to actively work to change how the body physically responds to emotional stimulus. It is not always easy to change. In fact, we often resist it quite strongly, especially when it requires a lot of effort and hard work. The truth is that when we become more aware of when our body is responding to stresses – oftentimes to things that we weren’t fully aware of – we can begin to re-write the software so that it doesn’t tell our body to be hyper-vigilant, but instead to stand down. Many years after first struggling go figure out what was bothering me I have begun to understand how to unwind from that process by paying more attention to how I am physically reacting to “emotional” threats. The amygdala can’t differentiate between the two so we have to consciously re-write the code that drives our body’s response to the world.

I want to return to the question of why more women struggle with many of these issues. Let’s look at the situation that a young female academic who hopes to get a PhD and eventually get hired as a full professor might face. This woman’s intelligence, skills, and abilities might have helped her to get through the gauntlet of college admissions and the heavy course load of college. However, getting a PhD requires an even greater level of direct approval from individuals who supervise their work. The candidate’s future success relies almost entirely on a small number of people, often a single supervisor. Further, not only does she have to deal a rigid hierarchy, she has to create work that fits within a very static system of knowledge. Ideas that challenge the overriding paradigms of that system are not embraced, so the pathway is very narrow. This can be enormously stressful, especially since so much of her future depends on only a few people’s support.

It is also likely that she will have to put up with a certain level of unconscious intimidation from those who are higher on the food chain. Privilege often blinds us to the small transgressions that less powerful people have to put up with, and these often feel enraging. To express that rage puts one’s ability to climb the ladder at serious risk. This kind of stress is exponentially greater for women. One can only imagine how much more repression is demanded from women of color. In order to stay on that path, the repression has to be so strong as to become unconscious. If the individual were aware of the feelings and the anger about it, then she would be responding to it. This would mean that she would likely not last in that environment.

In fact, if we start to look at these issues through this lens of relative privilege, and the consequent level of repression that is required to remain within a system, it might not surprise us that when we look at the auto immune condition that we refer to as Lupus, the numbers illuminate this pattern directly. Here I am going to copy a paragraph from a post I wrote earlier this week.

I recently had the pleasure of sitting next to a prominent African-American scholar on a flight home from a film festival. She told me about her daughter, who had a very supportive and fairly easy going upbringing which included a private Quaker school in Cambridge and a relatively uneventful four years at Yale. When she finished college, she went to get a law degree and a PhD at the same time, and within a few months was diagnosed with Lupus. When I mentioned the possible connection to the stress of taking on so much work, my seat-mate told me that this idea was interesting because so many of her daughter’s colleagues in Academia, who were also African-American, had come down with Lupus as well. When I went to look at a web page about the causes of Lupus” this section jumped out at me.

Lupus discriminates against African American, Latina, and Native American women

African-American women are three times more likely than Caucasian women to get Lupus and develop severe symptoms, with as many as 1 in every 250 affected.And the disease is two times more prevalent in Asian-American and Latina women than it is in Caucasian women. Women of Native American descent are also disproportionately affected.

If we examine these figures from a bio-physical perspective only, we might look for race- and sex-based genetic markers. We might even find some that we think point to possible causes – and might pursue possible cures. However, if instead we look at those words and read them as plainly as they are written, we see that this issue “discriminates” (as the article quite literally states) against women in direct relation to their relative privilege in society.

In order to succeed within a system of power and rules, one must either “get with the program” and accept those rules as natural law, or possess unparalleled social skills which allow them gently to prod and push at the rules. In either case, a great deal of emotional repression is involved. Rejecting the status quo outright leads to a great deal of conflict that impedes an individual’s ability to do well within that system. Those with relative levels of privilege based on race, class, or family/klan affiliation face less direct demands and are also often blind to the level of repression that is demanded of others. In fact while they may express rage at getting passed over for a job they think they deserve a sense of privilege makes them less likely to repress that rage. Those who challenge systems directly without any level of privilege are often ignored, forgotten, and passed over in terms of honors, support and jobs. Women of color, who are challenged by two different societal conditions, have to overcome even greater obstacles and might also feel even more isolated in these environments that those who enjoy privilege rarely consciously comprehend. (This was clearly illustrated in the 2016 film when one of the characters was forced to cross a large campus to go to the bathroom because thee wasn’t one where she was workingHidden Figures). As Dr. Maté points out in another clip from our interview, stress coupled with isolation creates an exponentially more damaging affect on people’s health.

On a personal note, my mother had breast cancer when I was a teenager. The cancer appeared during a time when she was often severely at odds with her boss. I recall her coming home from work angry about it, livid actually. While she had many friends and supportive colleagues I am sure that it still felt isolating and stressful to be in a situation with so much conflict that she had very little power over. She has stated that she thinks the two are connected.

When we look at how chronic fatigue is described by the Mayo Clinic, we see a pattern similar to Lupus in describing the possible causes and risk factors.

Causes

Scientists don’t know exactly what causes chronic fatigue syndrome. It may be a combination of factors that affect people who were born with a predisposition for the disorder.Some of the factors that have been studied include:

-Viral infections. Because some people develop chronic fatigue syndrome after having a viral infection, researchers question whether some viruses might trigger the disorder. Suspicious viruses include Epstein-Barr virus, human herpes virus 6 and mouse leukemia viruses. No conclusive link has yet been found.

-Immune system problems. The immune systems of people who have chronic fatigue syndrome appear to be impaired slightly, but it’s unclear if this impairment is enough to actually cause the disorder.

-Hormonal imbalances. People who have chronic fatigue syndrome also sometimes experience abnormal blood levels of hormones produced in the hypothalamus, pituitary glands or adrenal glands. But the significance of these abnormalities is still unknown.

The next page of the site lists risk factors

Factors that may increase your risk of chronic fatigue syndrome include:

Age. Chronic fatigue syndrome can occur at any age, but it most commonly affects people in their 40s and 50s.

Sex. Women are diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome much more often than men, but it may be that women are simply more likely to report their symptoms to a doctor.

Stress. Difficulty managing stress may contribute to the development of chronic fatigue syndrome.

There is only one risk factor that can be controlled for here: stress. As we have discussed, women are subjected to an inordinately higher level of demand for emotional repression in our culture – especially those women who try to compete with privileged males in the working world. The Mayo Clinic info suggests that women report Chronic Fatigue symptoms more – and sex may may well be bio-physical factor – but this puts the onus and responsibility on gender traits rather than on emotional repression required by that gender’s position in society. This system sees stress as a possible “risk factor,” but seemingly fears asking the question, “Is stress possibly causative?” If they did ask that question, they would find reams of studies that show stress has a massive impact on the immune system and the hormonal system. Shortly after my father died, my mom had a thyroid issue – I know without a doubt that it had to do with stress. They are related.

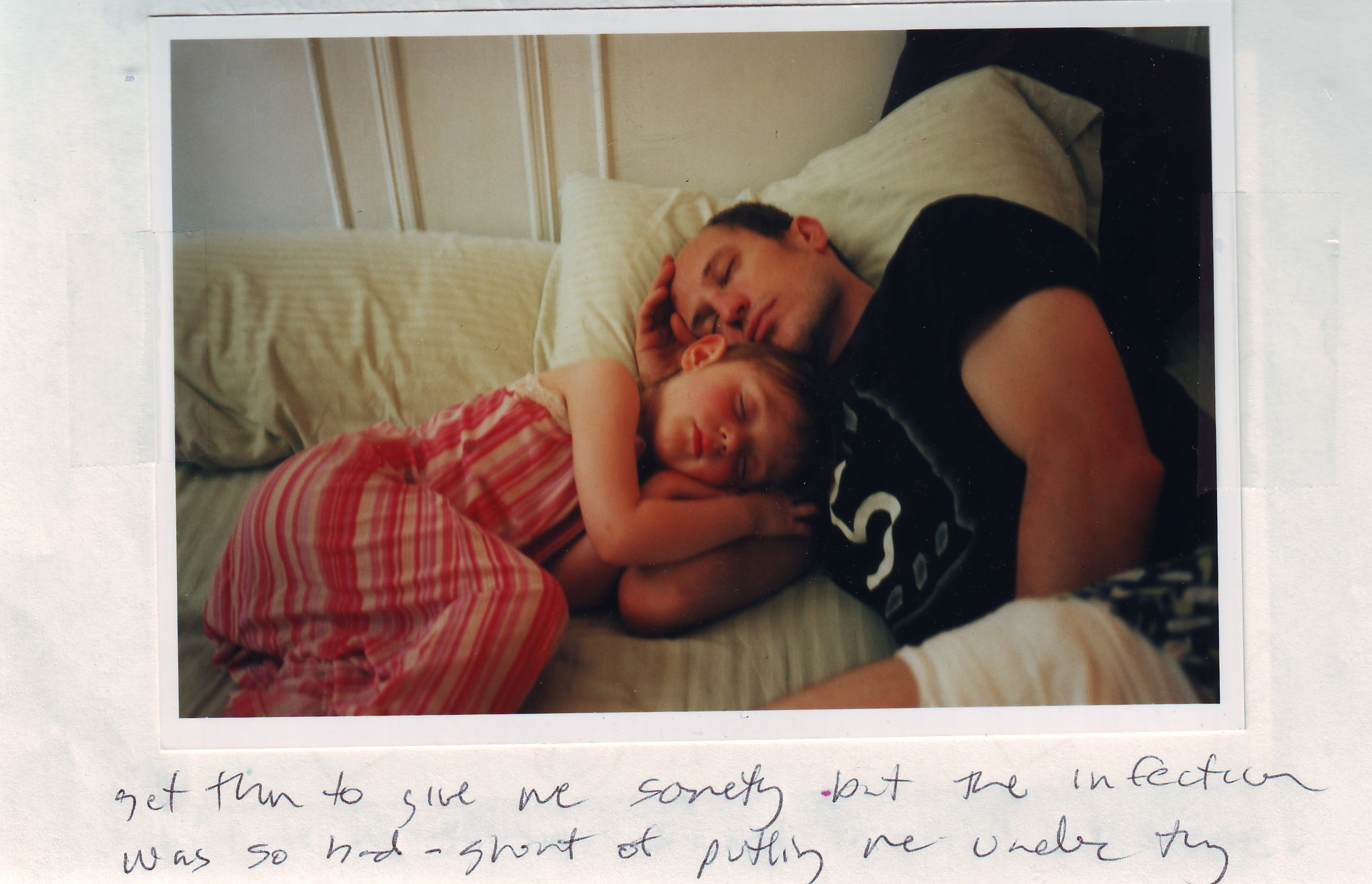

While the medical system is examining the possible connection between certain viruses and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, it acknowledges that many people carry these viruses without presenting with symptoms. The same is often true with certain types of bacteria, where some people carry them but don’t get “sick.” I once almost died from a staph infection. I was in the hospital for a week on a powerful IV drip antibiotic. At the time, I thought I might have gotten this MRSA (a highly antibiotic- resistant type of staph) when my wife and I went to the hospital to deal with a miscarriage at 2 and a half months. I didn’t realize it then, but now it seems obvious to me that the grief I was both experiencing, and unconsciously repressing, weakened my immune system which allowed the bacteria to thrive. I have no doubt of this whatsoever. We had named this child. We already had a three year old, and that in itself meant in some ways that we had to “hold it together” for her sake, or so we thought at the time.

Concepts of stress and the repression of emotions are difficult to articulate, to discuss. If we as a culture don’t even consider or examine the relationship between our stress and our emotions – or more precisely how our unconscious emotional response to the world affects us physically (if we fail to recognize the connection because we aren’t fully conscious of the emotions and don’t feel like we can control them) – then we have less chance of getting better. However, if we simply turn and address those painful feelings and emotions- we then have a chance of getting better.

Pol

Posted at 21:44h, 31 JulyGreat post! Awesome!