23 Apr Lessons Learned

I started this article last year as a series of Facebook posts about our films – one of those 10 films in 10 days challenges. It’s actually more like 11 or 12 films and it took me a few months, but now that I’ve done it, I figured I should pull it all together into one longer post. It has taken longer than I intended. In the meantime parents have been in the hospital, I turned 50, I met a daughter I didn’t know I had (yes, it will be part of yet another film), I got immersed in other projects, and we got protested. So it goes.

Lessons Learned

We’ve been doing this work for over 25 years and have made all kinds of films- from rock and roll narratives to crime films to political and personal documentaries. On the surface, most of the films don’t seem connected, but certain themes run through them all, and they build on one another. These can be thought of as themes and also as lessons we learned from making the films. One theme that runs through all the work is skepticism about systems: be it the music industry, media, political entities, those in power, art, corporations, medicine etc. In general, we’ve come to see that systems, while they provide useful structures, often get mired in corruption that they are blind to. Lesson 1: all systems are corrupted. I don’t think this leads to the argument that we need to destroy all systems, but instead that we should be skeptical about them, expose the issues that keep them stuck, and hold them accountable for the inherent problems they create.. The problem is, if you make films about the problems with systems, without having a system to back you up, you’re kind of shit out of luck. Lesson 2: if you’re gonna make work that calls attention to systemic problems, don’t expect anyone to rush into the breach and lift you up. So it goes (I’ve been trying to get my daughter to read Vonnegut for years). “So it goes” is a lesson in radical acceptance, which is something we need if we are going to raise questions that few want to hear.

We started out making films about the underground music world, which led to a documentary about an underground publisher and a discredited biography of G.W. Bush. When that was done, we helped make a film about protests at the Republican National Convention. We took kind of a right turn for our next project about a search for a serial rapist, but that film was also about media and how stories move through the world….. I’m getting ahead of myself… so I’ll start at the beginning

Half-Cocked was the first film that Suki and I made with the collaboration of some of the most creative people on the planet. I wrote a long post about the first tour by my band Sleepyheadthat connected us to the fine folks in Louisville, Chattanooga. Knoxville, and Nashville. I need to write something longer about the whole process of making it, and I will someday. However, in this post, what I want to focus on is the body of work, and how it all holds together.

When I met Suki Hawley, she was in graduate film school at NYU. I was in a band and taking tons of pictures at shows and on tour. I always knew that I wanted to make art but didn’t see myself as an “artist”. I certainly wasn’t a musician, but when I was in college I formed a band with a couple of friends. We learned how to play together and that helped us to create something a bit unique. We were far from “successful”, but being in that band created a pathway into a life spent making art. In the early 90’s it was still possible to find a very cheap apartment, work a few days a week, and make art the rest of the time. My room on Ave B cost me $150 a month, so a few shifts a week as a messenger or a busboy gave me plenty of freedom. I spent a lot of time writing, drawing, and making images. I shot some as I worked as a messenger, but most of my photos were of bands.

Actually, the summer before I started the band I drove across the country and took photos in malls. It was the year after Guns and Roses had broken big, and a couple of years before Nirvana did. Just before that trip I had seen Nirvana at the Pyramid in NY. I hadn’t really started shooting at shows so much then so I didn’t have my camera that night. I’m starting to get off topic, but the reason I bring it up is that my pathway into filmmaking was through music and photography, and it was this mix that led to the making of “Half-Cocked”.

I met Suki through her roommate who was in a band we often played with. Shortly after meeting we started to spend a lot of time together. She had already gone to film school as an undergrad and complained about the fact that NYU was kind of a waste of time. Eventually I talked her into dropping out of Film School. In addition to having gone to Weslyan for film she worked in LA for a couple of years as an assistant editor. The summer after we met she worked as the directors assistant on “Party Girl”, and shot-listed the entire feature. It was clear that she knew what she need to know in order to move forward. She finally agreed and that winter, we set to work making Half-Cocked. From the start, we knew that he film was meant to be a hybrid documentary – though that term hadn’t really been coined yet. We wanted to continue the documentation of the underground that I had been doing through photos, but we didn’t feel like we should make a documentary. Suki had focused on classic Hollywood Cinema at Weslyan and I had studied a lot of social sciences which led me to internalize a kind of colonialist/anthropologic idea of documentary that demanded “critical distance” from a subject. I felt like I was too much a part of that world to make a “documentary” so we tried to think about how to tell a story that would capture the time and place as a document. 25 years later I feel the opposite is true about documentary; that if you have too much “critical distance” then you are likely coming from an unconsciously colonialist perspective. It’s a complex issue, and there’s a space in which people who are a part of a community can document their world without making propaganda. I also believe that it’s important to work to find “open awareness”, in which we observe the world with awareness of our own internalized bias, work to address that, and make room to respond when holes in that mechanism are pointed out. If our thinking isn’t evolving then we cease to grow and learn.

We wanted the film to be as collaborative as possible so we tried to write a script that left a lot of room for input. As we put it together, we meant for the rough script to give a sense of the motivations and needs of the young characters. The idea was that the people, who were not playing themselves per se- but some version of themselves, could shape their character’s actions within the template that we’d set up. While it is entirely a fictional story, it was meant to document that scene.

Suki and I did a lot of brainstorming sessions with our roommates, Steve Thornton who lived with me, and Cynthia Nelson who lived with Suki. Then Suki and I would spend days at a time pacing around her apartment trying to pull together a story. We were enamored of teen riot films like Penelope Spheris’ “Suburbia”, as well as the films “Over the Edge” and “River’s Edge”. We also looked at Cassavetes films for their use of improvisation as well as the way he used the camera in a way that almost felt like a documentary.

Once we had a script together we sent it to my father, who was a passionate lover of films, for notes. In high school I rarely turned in a paper without my father first ripping it to absolute shreds. He didn’t mark up this script. Instead he sent it back with one slight sentence on the cover sheet, “Where the fuck’s the conflict?“.

He was right. We loved the characters a little too much, and they were written to be so close to the people who would play them, that it was hard to find the conflict. Like I said, it’s tricky to inhabit a space in which you are documenting something you are a part of. We had also sent the script to all of the participants hoping they would flesh out the story. In general, everyone was kind of busy with their own projects and the main actors had a record coming out days after we planned to finish the shoot. While they committed to being in the film most of them never really looked at the script until we arrived for the shoot. Only one person called us with notes. He wanted to add in all kinds of sub stories about kidnapping a pizza delivery guy and keeping him in the basement. They were interesting stories, but they didn’t really fit in with what was there. We had created a somewhat standard three act structure with an inciting incident, so we couldn’t figure out how to incorporate those notes (though we did make them part of a scene). This caused some conflict, but there were so many other conflicts that it kind of receded into the background.

One other character, Ian Svenonious, re-wrote all of his parts with incredible panache and creativity in the way that we had hoped. However, he didn’t inform us until he showed up, so it threw us off track a bit. We had a minuscule budget so we had to be incredibly organized in order to get it shot in the time allotted. Once we did a few rehearsals though, we found that he had been able to change his part without upsetting the flow of the scenes. In fact it helped make the film wildly stronger. However, he also informed us that he and his crew could only stay for a few days. Originally they were supposed to show up at the end to create a conflict that brought the film to a close- so we had to do some fast thinking to come up with a new ending.

The two weeks of prep and shooting were some of the hardest weeks of my life, but also some of the most creatively rewarding. I had never really shot film before (I audited three weeks of the film class sight and sound so I had shot a couple of times with a film camera) but thankfully we were able to get a talented crew together. The sound guy, Peter Schneider, was a total pro and Dave Ford rented us his camera and then came along as the assistant cameraman who taught me what he knew with great patience. He lit almost the whole film with a simple Chinese lantern because it gave a soft even light that allowed us to get an exposure quickly and naturally. We would have been lost without their supportive guidance.

While the shoot was tough for everyone, Suki and I had probably the hardest time of all. I have a tendency to want to combine things in creative ways; to be expansive. Suki wants things to be in control, and needs clear and manageable plans. My desire to throw new ideas into the mix was intensely stressful to her. At the same time, her need for a certain level of control over the film led to a lot of conflict, which almost killed the project and our relationship. The night before the first day of shooting I quit. The tension during rehearsals had become almost insurmountable. and I couldn’t see how we would able to work together. Further, that tension was making the whole set so uncomfortable that I didn’t see how we cold possibly pull it off. Thankfully, our producer Rachael talked me down. In the end, we probably could not have completed the film without some of the control that Suki wanted, but we also could’ve communicated about it better. 25 years later we are still finding a balance between our opposing ways of being in the world. From the beginning we each saw some value in the other person’s way of being, but it’s taken a very long time for us to fully embrace the balance between those two poles.

The last few days were the hardest because everyone was exhausted and totally over the process of making a film with no money. In addition to organizing the shoot, Rachael had also cooked most of the meals. In general, our locations were also where we were staying, so while we were shooting Rachael would be cooking. The whole thing got shot for around 7 grand- which came from an advance on the soundtrack. The plot involves a girl stealing a van from her brother. We used my band’s van and one of the actors van for the shoot. One was the production vehicle and the other was the character’s ride at all times. All 12 or 15 of us traveled in the two vans and two cars. It was like a mini rock tour. Three cities in 10 days. Honestly, what we did was pretty much impossible. Thankfully, I didn’t know that when we started, but the impossibility began to become into focus as the days wore on.

On the very last day we had a 14 hour shoot scheduled at a rock club. Originally, Ian was supposed to show up with his band and steal his van back. However, since the wasn’t there we decided to have the main character get arrested. Rachael had arranged for an off duty Nashville cop (who looked like the Terminator) to show up for an hour for 50 bucks- with a car. How she did that I still don’t understand. He was coming at 8 so we really had to have everything else shot before then.

We got in around 10 am to get set up and were informed that there was a Sunday afternoon hardcore show from 3-6. After about 3 minutes of confusion we cut about half of our shots so that we could get it done and quickly shot our back stage interior shots. When the band showed up we made up a couple of scenes to shoot outside while they rocked. (It was Fred Armisen’s band trenchmouth) So we improvised a scene to shoot outside while the show went on. It was actually something we really needed, so that worked out. The band finished a little early and we shot the final rock show in a couple of hours. James Murphy, who went on to form LCD Soundsystem, had been on the shoot for the first 10 days and recorded the early music. He trained the other guys well and they got great great sound that night. The cop showed up right on time to arrest Tara. Thankfully Suki had the vision to see that we needed a final shot from the roof, of the car driving away and panning back to the band. We got it shot by midnight. I think there was some kind of party that night but I have a vague memory of fighting with Suki in a car instead.

When we got back to NY we rented a flatbed editing desk (a Steenbeck) and Suki got to work cutting it in her closet- it was a big closet that had previously housed her bed. A couple weeks after we got back from the shoot, my band played in DC, and while we were there we got Ian to record some phone messages we needed for the film. On the way there I took a roll of photos and made a collage for Suki to hang on her wall. There are a number of images of the Delaware memorial bridge. At the bottom there’s a shot of Ian hitting a cigarette machine. A couple of weeks later while I was on tour with Yo La Tengo Kurt Cobain died. I was pretty upset about it and it also felt a little bit like the end of an era. While I was gone Suki had to move out for a few days so they could shoot a low budget feature called “Kids” in her bedroom. Our friend Dave Doerneberg was the prop master and he left the collage I’d made her on the wall, so Ian is actually kind of in “Kids” (that’s him in the lower left hand corner of the collage just above the motorcycle. I wrote more about that here, and you can see the whole collage. It took about 6 months of solid editing time and after some begging and borrowing we got a sound mix done and a work print made. We had tried to do a few rough cut screenings but that involved having 3 or 4 people squeeze into the closet to watch it play back on the Steenbeck.

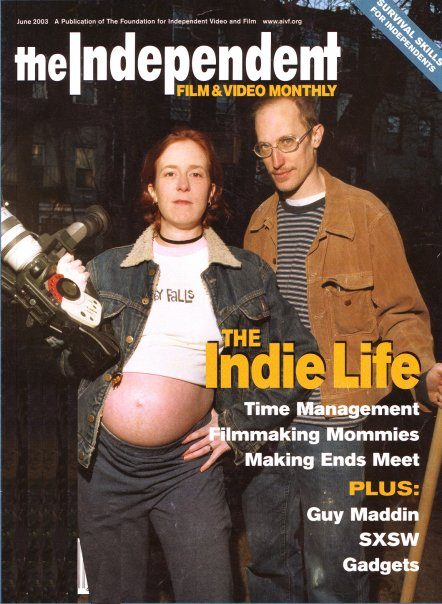

When we finally had a print made it was a revelation to see it on a screen. We rented a place called millineum film works and had the cast, crew, and friends come to see it. The response was great and a few days later a review showed up in Varietybecause our friend Phil had brought his friend Godfrey Cheshire who loved it and wrote the review. We hadn’t met him nor heard about a review so we had no idea why every studio in Hollywood was calling us. We kept packaging up VHS tapes to ship out. We had made 50 so we could submit to festivals- and soon we had a stack of them packaged up on the floor. Finally someone called and told us about the review. We never heard back from any of the studios, and we also got rejected from the first 35 festivals we applied to.

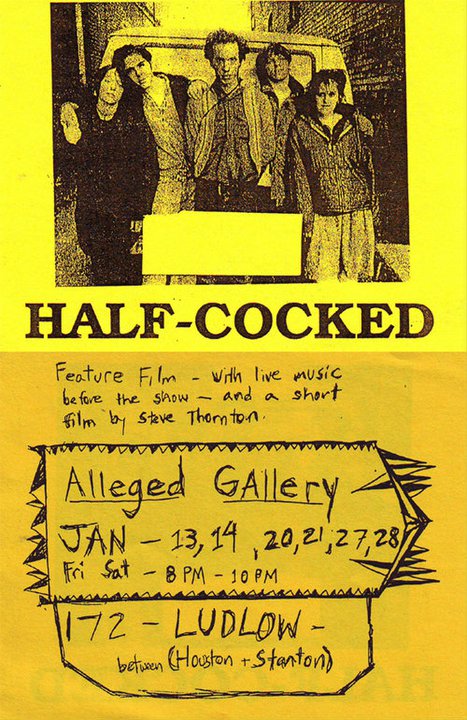

After about six months of waiting around we decided to go ahead and release the soundtrack with Matador Records (who had generously funded most of the film with an advance on the soundtrack) and it started to get a lot of positive attention. We began tour with the film, mostly showing it in rock clubs with a 16mm projector from our single print. Some of those events were amazing. We did one at the Middle East in Boston with Helium and Come. A few months later we decided to have Matador do a release of the VHS and we went and toured the West Coast with Fuck, whose record was just coming out. Eventually the film began to play some of the underground film festivals- and we set up a 3 weekend run at the Alleged Gallery on Ludlow street in NY. Those were amazing shows with bands like antietam and yo la tango playing acoustic opening sets.

While it was great to get it seen, touring was kind of depressing because showing a film isn’t the same kind of emotional release that playing a show is. While each show is different, it’s not different enough to justify the 6 hours of driving and sleeping on floors for 50 bucks at the door. We had started to write a new script with our friend Tim Foljan and we e had a good time working together so we decided to form an improv band and tour with “Half-Cocked” to kill the boredom. That was fun, but we weren’t able to get that film off the ground. A year later I was on tour in Spain and the promoter suggested bringing “Half-Cocked”. I loved Spain, so when I got back I told Suki about the plan with great excitement. She burst into tears at the thought of continuing to show that film. So I convinced her that we could make a film while we toured- and we’d shoot it in Spain.

Lessons Learned:

1. If you want to complete a project start telling people about it. This kind of forces you to move forward and creates momentum

2. If you start telling people about a project, start working on it, because if you don’t, you are less likely to complete anything ever.

3. If you are going to work on a project think it through before you start telling people, because once you start talking about it, it takes on a life of it’s own and without some kind of foundational ideas it can get away from you pretty quickly

4. Collaboration is powerful, but it’s also difficult.

5. Sometimes the work that we make has one value in the present and another in the future.

6. If systems don’t embrace your work- in this case the film system did not, embrace the system that does- the music community embraced the film so we took it there.

7. Don’t get too wedded to an idea. If you stop looking, you miss opportunities that arise. This doesn’t mean that one needs to be completely free and open to whatever happens, but when shit happens that you can’t control, see it as an opportunity for something great. Half the time it won’t be great, but when it is, it can be fantastic.

After things had calmed down and we started to talk about what a film shot in Spain might look like it began to take on a real shape and a sense of momentum. Unai began to book a tour for the films (“Half-Cocked”, “Mod Fuck Explosion”, “Speed Racer” -about Vic Chestnutt, and “Wild Girls Go-Go-Ramaa”) and Suki and I decided to get married. Shooting the film would be our “honeymoon”.

We had learned a lot from making “Half-Cocked”. There were some good lessons about how to put a script together and then get that story on screen. Still, we had some very serious challenges; half of the film would be in Spanish, and we were going to once again be working with non-actors. We came up with a story about a tour promoter who uses tour support money to buy speed to sell on the road. The promoter is actually devoted to the music, but the clubs don’t pay enough to cover the costs of bringing in bands from other countries so he essentially sells the speed to subsidize the band’s adventures. However, by the time we meet him he’s worn down and struggling. When the band Come arrives from the US he picks them up several hours late and then screws everything up so badly that they leave. However, he’s already bought the speed with the tour support money so he asks the opening act, a wild performance artist, to go with him. He genuinely sees a spark in her but things fall apart. So did our production.

The wedding was a blast, but it was another big production- and we were trying to pull off both things at the same time with limited resources. A couple of weeks before we left, our main actress quit. We found a new one who turned out to be incredibly creative, but a week later our gaffer informed us he wouldn’t be coming. Sean, who had been in “Half-Cocked” came along to do sound, and another musician friend came along as the Assistant Cameraman. At the very last minute we found a gaffer, but he turned out to be a lightning rod for trouble.

We got married at the Brooklyn Brewery where we struck a kind of incredible deal for the whole day and night plus all the beer we could drink. We kept the ceremony very small, just family and the closest of friends- then had 300 people come drink while band played. It was nice September night so the party spilled out onto the street. About three days later we left for Spain.

We had a few days to get prepped once we arrived. We set up a relationship with a film lab and did other housekeeping like that while we also tried to start to work with the actors and secure locations. Unai, our promoter was playing the tour promoter “Unai” and he was also producing the film on the ground. He’d secured most of our Madrid locations and we also planned a lot of impromptu street shooting. The plan was to shoot for four days in Madrid, then hit the road to Barcelona (along with the film tour), and then onto Bilbao.

From the start things went a little crooked. A good friend of mine had come along to help but immediately began to undermine our authority by making fun of us when we tried to get things going in a serious way. He kept pissing off the gaffer by using his camera with a flash. The gaffer was incredibly high strung and though his lights were blowing. My friend and other started to make fun of him and the energy was tough. We were all crashing in Unai’s apartment, but after a few days we had to get some hotel rooms because it wasn’t working out. I came down with a very bad cold that plagued me the whole shoot. Once we got the cameras rolling it was clear that Unai was going to be great on camera. However, the energy and presence of the European Actors was very different than the American ones so we had to work to find a middle ground on screen.

Radiation “trailer”from rumuron Vimeo.

Our first shoot was supposed to be at a Helium concert, but the band didn’t show up in Spain. We saw that Stereolab was playing, and their lighting designer was a friend of ours so we reached out. After a lot of effort we got in touch with her and she arranged for the band to jam for a bit at the end of the show so we could film without having to deal with the hassle of licensing published songs. It ended up working out great. Unai is the promoter that night and meets a girl whom he goes home with. All of this is done as the Opening credit sequence. When he gets home to his girlfriend late the next morning she blows up at him and kicks him out of the apartment- throwing all of his records into the street. He’s already late to pick up the van to get the band so things get off to a great start. Those first two shoots went pretty well. It took a lot of coordination to shoot at a loud concert and get the footage we needed, but somehow we did.

From then on the shoot quickly descended into chaos. Unai was incredible as the star, and Katy Petty created unbelievable performance pieces for her character, but things were disorganized and the crew and actors started to show up later and later, so we increasingly fell behind schedule wise. In addition to making the film we were still doing the film tour. We had set it up so that the tour locations could be our filming locations. It made sense on paper but not so much in reality. The actress who played Unai’s girlfriend in the first scene of the film, Maria, ended up taking over the film tour because there was no way that Unai could do both. The day before out wedding in NY she was our waitress and recognized me from a promo photo on Unai’s wall in Madrid. It was a crazy coincidence, but we agreed then and there that she should play the girlfriend because it turned out she was going back to Spain in a couple of days. She was a terrible waitress, but she saved our asses on the shoot.

It was incredibly difficult to make a film in a foreign country with almost no resources and an impossible schedule. On the fourth or fifth day our schedule called for wheels up at 9 am so that we could get to Barcelona by the early afternoon. The crew had been out late the night before and started to roll in around 11. We finally hit the road at noon. At about 1:30 we pulled into a small town to shoot a couple of scenes. In the story Unai and Mary (Katy’s character) leave late and night and just start driving- in this scene they are waking up in a small town. We got that scene shot and then discovered a folk art sculpture garden, so we quickly improvised a scene where Mary wanders around with the artist. When that was done it was 2:30 and everyone was starving but everything was closed. The crew was really pissed off, especially the gaffer. When the AC started to yell at me I calmly pointed out that call time was 9 but no one came till 11, and that he couldn’t claim that we weren’t being professional if he was coming in two hours late. He heard it, and quickly dialed it back and apologized. Sometimes the dynamic on set can get bad but after that things pulled together a little. Still, the gaffer continued to get worse.

We got to Barcelona and we shot at the Come show. That gave us an audience for a kind of triumphant show for Mary. That night the print ripped while we were showing Half-Cocked and Suki had to pause the scene we were shooting in the hallways so she could splice it together. After that the tour went on without us and we headed to Bilbao. On the first shoot, in Unai’s house, I pointed out to the gaffer that I could see one of the lights in the shot. He freaked out screaming “Re-light” then proceeded to destroy many of the lights he had pieced together. Then he disappeared. The AC and I lit the rest of the film ourselves. We never saw him again.

Somehow we got the film in the can. I had terrible cold for most of the shoot- and not sleeping only made it worse. When the shoot was over Suki and I checked in to a windowless hotel in Madrid and succumbed to a devastating stomach bug for several days. Neither of us was able to take care of the other. I guess you could say the honeymoon was over.

When we got back to NY we bought a video editing system and spent 5 thousand dollars on a 36 gb hard drive to edit the movie with. Once it was assembled it was a bit of a mess. Eventually we figured out that it needed a “Sunset Boulevard” kind of voiceover and we flew Unai to NY to record it. Thankfully it did what it needed to do and the film came together. To our great surprise we were invited to Sundance and SXSW. Despite hiring a wily publicist (he hustled like nobody’s business) we didn’t get much press out of Sundance even as we set up a rock show where Come and Two dollar Guitar played. Aside from our crew, the room was empty except for three patrons, one of whom was Michael Stipe. The bar threatened to kick us out if we didn’t get the bands to turn down so I tried to gently bring down Thalia Zedek’s guitar volume and thought I might turn to stone when she turned my way. I can’t remember ever feeling worse than in that moment.

A couple of weeks later though we screened the film at NYUFF and had a huge event at CBGB which included an opening of a massive photo show.At that NYUFF screening folks from the new distributor Palm Pictures approached us with great excitement. They thought the film would be perfect for their new division of Island Pictures. The following day the same thing happened at our screening at SXSW. They hadn’t been in contact but these reps for Palm also thought it was perfect. The Palm executives also agreed on one condition: that NY’s Film Forum book the film. The theater declined, and that was that.

Still we showed it in a dozen countries and got to travel to Buenos Aires, Bangkok, and Gijon. It was a pretty amazing year of touring with the film and the photos. However, outside of the festival circuit it went completely unseen except for a shortened version on the Half-Cocked DVD we put out in 2007. This is the first time it is available. We showed it at the Quad last February and the response was amazing. We recently re-scanned the negative of Half-Cocked- Radiation is at the lab right now to get the re-scan treatment.

Like “Half-Cocked”, “Radiation” was meant to document the scene- to create something of a time capsule snapshot in narrative form. “Horns and Halos”, our next film, was a straight up documentary, and it was another film with one foot in underground culture.

Our first two films focused on underground music culture. As our travels with Radiation wound to a close, and I turned 30 I fell into a job at an indie rock web start up called Insound. It was my first full time job after a decade of working as a messenger, PA, and photographer. The founders of the site were barely of drinking age, so my job had a lot to do with simply connecting them to underground music, film, and literature people. One of those connections was Sander Hicks – whom I hadn’t met in person – published books of poetry and politics. Many of the authors he worked with were also musicians, so I had arranged to get his books up on Insound. After about a month of working there, he sent over a press release about re-releasing a discredited bio of G.W. Bush. The book had been pulled from bookstore shelves because it turned out that the author was a convicted felon who had denied it when confronted by the Dallas Morning News. That book, “Fortunate Son” had created a big stir because of a hastily added afterword alleging that W. had been arrested for cocaine possession but his father had gotten him out of trouble.

Interestingly, Suki and I had seen a one paragraph story about it in the International Herald Tribune while on a plane back from Thailand (where we went with Radiation). So, when we got Sanders’ release we thought… this might be a good subject for a documentary. We had recently gotten a video camera and, feeling burnt out by shooting two narratives on film, we thought maybe we’d do a documentary because we could do everything ourselves. It’s important to remember that non-linear video editing was fairly new, and we had a system that we had purchased for Radiation. I called up Sander and asked if we could talk to him about shooting a documentary. He barked into the phone, “Sure, sounds great. I’m doing the sweep-and-mop on Saturday, you can come by then.. gotta go!” Seeing as I didn’t know where he lived or what a sweep-and-mop was, I had to call him back. “Yeah right, I’m the super of a building in Lower Manhattan and squat the basement for the publishing company. I have to sweep and mop the halls on Saturday, you can come by then- I’m too busy to talk any other time.”

So, that Saturday we showed up at the building off Delancey street and as we walked up with the camera Sander started speaking and didn’t stop for several hours. We knew that we had a character, which meant we possibly had a movie. Since I was working full time, Suki also started to go by to shoot when things were happening and I couldn’t get there, and a lot was happening. We followed the story for a year, through the election and thought we were done. However, more action took place and we picked it back up.

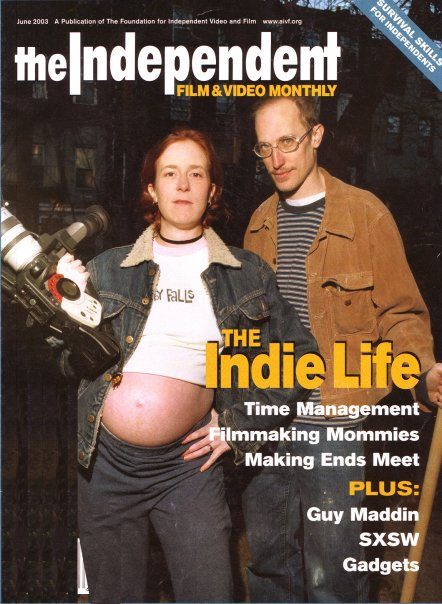

Needless to say, the film has a slight negative slant on GW Bush. Unfortunately for us, our last day of shooting was Sept 10, 2011. At that point we were almost done with the editing and had started to submit to festivals and Bush was increasingly unpopular. The following day the Towers came down and for the next 10 months the thought of anything that raised questions about our dear leader was verboten. We took the film to the Rotterdam FF that winter where it was well received. However, seeing it with a big audience made it clear to us that we needed to make drastic changes. We cut out 40 minutes and added in a new 25 (meaning it went from 90 minutes to 75). We finished that cut two days before the US premiere as opening night for the NYUFF. About an hour after finishing it Suki went into labor with our daughter Fiona.

By the following fall resistance to Bush had started to grow, as did interest in our film. We self-distributed it and got it short listed for the Oscar (at that point you weren’t allowed to tell anyone- but you did have to make a 35mm print which cost 30 thousand dollars!!). We did pretty well with the distribution of the film and actually got it on TV in Latin America, Australia, Canada, and Cinemax in the US. As we wound down the distribution we started working on Code 33, Battle for Brooklyn, and All The rage.

About halfway through the process of making “Horns and Halos” we were approached by David Beilinson, who had met Sander in a bar, about helping us make the film. He was a recent NYU grad who was working at a PBS show for teens called “In the Mix” and wanted to get involved in longer term projects. He brought new energy to the process and came on as a producer. We worked well together and started to formulate ideas for new projects. He had a friend from Miami, where he was from, who had gone to RISD to study drawing and ended up doing work for the Miami PD as a sketch artist. Her renderings were often so good that they looked like she had drawn them by looking at the person they were used to capture. David wanted to pitch a show based on her work called “Sketch” where the idea was that we would follow each case from the sketch though apprehension. He got permission from the Miami PD and went down to shoot some footage for a pitch tape.

The first case he followed involved a man who had raped a teenager in her own home. David spent the week riding around with the detectives as they canvassed the area with the sketch. After about 5 days the rapist struck again, confirmed with DNA. Within a day, the police went into high hear and used the DNA to connect to connect the suspect to 5 other cases. I was in a movie at 10pm on a Sunday night when I got a call from David saying that he’d already booked me on a 6am flight because the story was blowing up and he wasn’t really a shooter. By the time I arrived MSNBC and CNN were broadcasting live from the scene. There were a dozens of other reporters and it was chaos. However, since David had been with the cops for a week, he was able to march me upstairs to the nerve center and I went in shooting. While the police were getting tons of tips due to the notoriety of the case, most of them led no where. Our daughter was just over a year old, but I got stuck down there for weeks at a time. We spent the whole summer following the case. We focused heavily on the strain that the case was putting on the officers we were following. Once we got some footage together we pitched the project to HBO since they had bought our previous film. They were excited by the project and gave us almost as much money to edit the film as they had to purchase our previous project. We set out to edit in earnest and got together a decent rough cut. HBO had indicated that they wanted to be involved in the project so we were excited to get their feedback. This was the biggest mistake we ever made in our film career.

To them, the rough cut was boring, and they told us they were done with the project. Well, we knew that we had something powerful so we continued to work on it and premiered it at the Miami Film Festival a few months later where it got ridiculously positive reviews in Variety and the Hollywood Reporter. A few weeks later we took it to SXSW where the response was equally powerful. An executive from HBO saw it and loved it, but deflated when he saw that HBO had helped but passed on it. At the time, HBO was really the only game in town when it came to purchasing films. We set up a screening for distributors, and most of them came, but they didn’t know how to market it and they passed. We continued to take it to festivals where it got a great response and we considered putting it in theaters ourselves since we had done very well with “Horns and Halos”. While we were considering that possibility, the rapist escaped from jail over the Christmas holidays. It was one of the top stories of that holiday season and our partner David was in Miami so he was able to film with the police while they went out once again to hunt for the suspect. They showed some of our footage to his ex girlfriend and a few hours later they got a tip about where he was.

The trial was set for the following spring and the police arranged for us to be the pool camera for the trial. At the same time, the cops in our film ended up working as murder detectives and were featured on the show The First 48 which was on A&E. Since The network considered them “their cops” they gave us a budget for shooting the trial and reconfiguring the film to include the escape as well. We turned Code 33 into Miami Manhunt as a two hour TV special. It lost some of its cinematic power, but it is kind of incredible in the way it goes from the first report of the crime to the capture, escape, and trial.

Shortly after completing “Horns and Halos,” I heard that the Republican National Convention would be taking place in New York. I went down to a first meeting of people who were planning to protest. In 2000 the police had infiltrated the protest movement and done massive pre-emptive arrests in Philly. I understood that there would be a lot of distrust at the meeting, yet it was not a secret meeting by any means. Near the end of the discussion people were asked to stand up and say something about the action that they were interested in participating in. I explained that I was interested in making a documentary about the protests and that I had been part of the team that made “Horns and Halos”. The film had had some impact so many people had heard of it. After the meeting I was approached by Gabriel Rhodes and Keefe Murren. They also planned to make a documentary and suggested that we join forces. They already had plans to follow activist Sheri Honkola, and wanted to follow a journalist and a political candidate. As the convention approached I was given the task of following Michelle Goldberg who wrote for Salon (now an opinion writer for the Times and regular commentator on MSNBC).

I first met Michelle when I went to film as she covered Sheri Honkola’s preparations for the event. The collaborative aspect of the filmmaking was very productive as I didn’t have the bandwidth to make a film like this by myself. However, we did have slightly different ideas and aesthetics, and I took something of a step back and let Gabe and Keefe take the lead. I also followed the satirical group, the Billionaires for Bush, but that thread was eventually cut from the film (embedded link above). Right from the start, at a Transportation Alternatives bike ride before the convention, the protesters were met with somewhat extreme violence from the police. I was riding on the back of Michelle’s bike and witnessed cops attack bikers and tackle them from their bikes. It was shocking. Even though I had been at a number of large protests, especially since the start of the Iraq war, I was unprepared for how aggressive the police were, and that energy only increased as the days wore on.

On the first real day of the convention, and the bigger protests, the police went into overdrive. I filmed in Times Square as they wrapped groups of people in orange netting and made mass arrests without any real provocation. Later that afternoon there were more direct action events and the police got much more aggressive. Michelle had a press badge and felt somewhat invulnerable. I did not have a badge and felt very vulnerable. I also had on headphones and Michelle was on a radio mic. At times I would lose her visually but could still here her which was very disorienting. At one point a huge line of cops in riot gear massed on the north side of 34th St at Herald Square. Protesters were being rounded on the South Side. Michelle spotted Chris Dunn, head of the NY ACLU and ran into the median to question him. He turned and shot back, “This is not a safe space, you need to leave!” Hustling around with a heavy camera and camera bag was exhausting and my leg was already sore from an earlier back problem. By the time the protest were over I had a mild form of PTSD. My whole body would tense up when I watched the footage. There was something deeply disturbing and disempowering about witnessing the police act with such impunity. There was no sense of justice, only a drive to clear the streets in order to present an “open for business” face to the nation.

Gabe followed Cheri Honkola around and Keefe covered the political candidate and backed up the coverage of Sheri and Michelle. When it was all over, we had mountains of footage. We hired an editor to put it together. Eventually I ended up spending a lot of time in the edit room trying to help shape it. The film turned out well, but it had a hard time finding an audience. I’m still quite proud of it and it’s an important snapshot that gives us some insight into how we got where we are now.

Broken Angel

Broken_Angel_Doc (extended trailer)from rumuron Vimeo.

In 2004 after the shooting was complete on Code 33, Suki was editing away, and I was doing a lot more of taking Fiona to day care and picking her up. After dropping her off at daycare I started to shoot on two different documentaries; one about the fight against a basketball arena and enormous real estate project that involved seizing property (about 7years later this became “Battle for Brooklyn”), and one about an artist’s fight to save his building, “The Broken Angel,” from being demolished. This was a wildly hectic several months.

When we moved to Clinton Hill in 1999, I would take my dog for long walks at night and I quickly discovered the Broken Angel, tucked away on an odd L shaped street called Downing Street. An artist, Arthur Wood, had bought the burned-out shell of a building over 20 years earlier for $20,000. He petitioned the city to let him build a guard shack in front of it for a watchman and got permission. At the time, much of the area was dotted with abandoned buildings, so in general the city didn’t pay much attention to what was going on. He moved his wife and kids into the guard shack and started to build out art and living spaces in the building itself. It formerly had 8 apartments, 2 per floor, that spanned front to back. The building never had heat, so in the dead of winter, they would move in with friends for several months.

Arthur began to turn the building into an Escher-like sculpture, adding floors and crazy rooms on top. When the building department issued him a summons for building additional floors, he got to work and took out two floor/ceilings and showed them that it was still only 4 stories high – one of the floors was now 30 feet tall. In my first five years in the neighborhood, I occasionally saw Arthur but never met him. In 2006, there was a small fire on the roof and the Buildings Department came in and forcibly removed Arthur and his wife. That’s when I found out that another parent from my daughter’s day care was going to partner with Arthur to develop the building into condos while preserving the space. I reached out to the developer, and he was excited to have us involved. The next day I filmed my first interview with Arthur. He was a bit prickly from the start, but slowly warmed up to me. Soon, I was spending several hours a day filming as they cleaned out the building. For years, Arthur had dragged junk back and filled the space with it. He also had mountains of art and other projects. Arthur is a master painter and his canvases were stunning.

While the developer declared that he wanted to follow Arthur’s vision as much as possible, he needed to get everything out of the building in order to get work done. There were literally tons of debris to clear out and Arthur was trying to save as much of it as possible. He had spent 20 years working on the building almost entirely by himself, so he wasn’t used to the pace that needed to be maintained with people on the clock. A construction loan isn’t paid out in one lump sum. Instead, there’s a schedule of work that needs to get done in order to trigger the next door. Within days, they were way behind schedule and this started to cause problems with the bank. The city also wanted to come in and tear down the top and charge Arthur for the work, so the developer, Shahn, had his work cut out just trying to keep them at bay. Eventually, Shahn got the help of the same city councilperson who was a main character in Battle for Brooklyn, and there was a slight reprieve on the city’s focus on taking down the sculptural aspects of the building.

Meanwhile, I was also doing a lot of shooting on our other film, “Battle for Brooklyn,” and trying to take care of two daughters. About 4 months after starting to shoot on the Broken Angel film, my father was hit by a car and killed. Three months later, we had our second daughter. I spent more and more time with Arthur and he became something of a surrogate father for me, as he reminded me of my father. Like my dad, Arthur revelled in his own irreverence. Soon Arthur’s wife became ill with cancer, and I started to drive her and Arthur to treatment each week. The following spring, I went to Japan with my family for three weeks. When we returned, I found that Arthur was dismantling the roof in order to move ahead with the construction. The building had been cleared out by then, and a lot of progress was being made on the project. I got there just in time to get some great shots, but also to get spit in the face by another camerawoman. She was shooting for a different project and felt competitive. She was so interested in Arthur that she decided to keep the tapes she had shot as a work for hire. The other filmmaker sued her and lost. Arthur liked her and started to freeze me out. He is so litigious that I realized I couldn’t waste time editing a film without his consent. Eventually, the bank foreclosed on the building. Arthur’s wife passed away and he was eventually forced out. While his building had been worth millions, he was left with nothing and it got developed into another bland boring condo building. Maybe someday we’ll get to finish the project.

Shortly after finishing up the distribution of “Horns and Halos” we stumbled into “Code 33”. As Suki began to edit that in earnest I started to shoot “Battle for Brooklyn” and “The Broken Angel Film”. At the time we had a small child and I did a lot of the day-to-day dealing with her so that Suki could focus on editing.

I saw an article in the NY Times about a new neighborhood “being built from scratch” at the corner of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues. There were some MTA rail yards there but also many newer loft conversions of old industrial buildings – as well as a couple of grand structures that seemed on the verge of being repurposed. Our daughter went to day care a couple of blocks from the site, so I was very familiar with the area. When I read the article, I was so confused: there was a neighborhood there already. I started to ask my neighbors at the playground about it and was told to forget about it. “The mayor, the governor and everyone else has come out in support of it so don’t even think about it. It’s not worth your time.”

Something about that depressed me. A few days later, I saw a sign screaming “Stop the Project!” There was a name and phone number on the flier, so I called and connected to Patti Hagen. She started to tell me everything that was wrong with this project as well as development in general. It was December of 2003, cold as hell and beginning to snow. I told her I’d be over in the morning as she led a series of journalists around the project site. I limped around the project site with Patti and crew as my hip was kind of out of whack (a problem that only got worse over the course of the next 6 months). I probably shot 4 hours of footage that first day and I knew that we had a story to tell. After about a week of following Patti around, she suggested that I reach out to Dan Goldstein because she believed he was the only “loft dweller” (what she called the neighborhood’s new arrivals to the loft buildings) who wouldn’t sell out. Most of the newcomers hadn’t developed deep roots in the neighborhood and were happy to take offers 20 percent over what they had paid the previous year in order to get out from under the threat of eminent domain. “Dan Goldstein,” I wondered out loud, “Is he a graphic designer?” Turns out he had designed the logo for the project’s opposition group, “Develop Don’t Destroy.” He had also designed the poster for our film “Radiation.”

Dan and I had spent several weeks together in Maine a decade earlier because he was the roommate of a high school friend of mine in college. When I met with him, it was clear that Patti was right; he wasn’t going to sell. In fact, she was totally on the money, because within six months everyone else in his building sold out. For the next six years, he was the sole inhabitant in a 32 unit building. He became the leader and face of the opposition. Given our personal connection, we were able to film quite closely. There were complex issues related to power, race, community, gentrification, planning, development, corruption, and coercion involved in telling this story. At the same time, it was important to keep it at a human scale level.

When we first started to make films, we were young people who were part of a music scene. By the time we started “Battle for Brooklyn” we were young parents, with a dog, and a home. For the previous decade we had less of a sense of rootedness. Once we bought a home and started to walk our dog we began to meet our neighbors with dogs. When we had a kid we started to meet all of our neighbors. Working for a decade on a film about community led to a lot of thinking about community. We ended up becoming deeply involved in our children’s school. The project had a powerful influence on our life, and that in turn had a powerful influence on the film.

For the first six months I shot constantly and it took a toll on my body. In addition to shooting that project I was chasing Arthur around the Broken Angel site and I got completely worn down. My leg gave out completely and I was in tremendous pain. At that point I ended up in Dr John Sarno’s office, a well know back pain expert who argued that most back pain was caused by the repression of emotions rather than purely physical causes. I knew he was right because my father and brother had both been saved by him. He helped me too and we started a film project about him as well. However, I didn’t shoot more than 6 hours of tape in the first years of it. As I slowly recovered from my leg problems I continued to shoot. I just go more strategic and focused about the process. I also wasn’t sure what to shoot.

When one works on a long term project with no end in sight it can be overwhelming at times. We applied for literally dozens of grants but had no success in raising funds. Finally, near the end of the project Kickstarter was launched and we ran one of the first kickstarter projects to raise more than 25k. We started to apply to festivals and got a lot of rejections before the film was invited to the Hot Docs Festival in Toronto in April 2011. While the film did great there – it was the 13th host popular film in the audience poll out of over 200 films- we couldn’t get any interest in regards to other festivals or distribution. So, we arranged to make it the opening night film of the Brooklyn Film Fest and hired a publicist- and then launched it theatrically the following week. The press was great and we did amazing at the box office that first week. However, no one else would book it. They saw it as a “local” story that wouldn’t be of interest to their audiences. I was so stressed out and frustrated by how difficult it was to get people to take the film seriously that my leg began to kill me again. I went and did q and a at every screening opening weekend and by the end of it I almost couldn’t get from my car to the theater. A few days after that run, I was completely paralyzed by the pain. I was slammed to the floor of my office and I couldn’t move. As I hit the ground I screamed grab the camera because I knew we had to re-start the Dr Sarno documentary.

It took over 3 weeks before I was able to walk again. It was a long slow recovery, and I was careful about not working myself into the ground as I tried to get the film out into the world, and slowly began to shoot with Dr Sarno. That fall The Occupy Movement took off and people recognized Battle as an Occupy movie. That awareness led to a lot more screenings and eventually it was short listed for the Academy Award. Still, we had great difficulty getting it distributed.

When I began to recover from the insanity of dealing with “Battle for Brooklyn” I started to work on the Dr Sarno film. At the same time we got some support to make a film about Johnny Gosch’s mother’s 30 year fight to find out what happened to her missing son.

About 10 years earlier, after a screening of our film “Horns and Halos” we had been approached by Nick Bryant, a writer who was in the midst of a project detailing an insane story of organized abuse of children that also included a tale of bank fraud and political blackmail. It was so wild that it was hard to wrap our minds around. However, our partner David really dug in and researched. The rabbit hole just got deeper. We spent many years trying to pitch it to possible funders but no one was interested, and it was so scary – many people who tried to look into it ended up dead- that it was hard to push forward. Eventually, we realized that one way into the bigger story of institutionalized abuse of children was through Johnny’s story as it was believed that he had been taken and pulled into this larger network of malfeasance. This story could focus on his mother and her hard work- which would give us a way to make a film.

Shortly after I began to recover from my back/leg pain, we got MSNBC to agree to help us make it. Unfortunately, they only agreed to fund a TV hour, which is about 45 minutes. After agreeing on the details of the TV hour, we asked them to agree to let us make a feature ourselves at a later date, and they said fine. The budget allowed us to shoot pretty much everything we needed for the feature, we just had to fund the edit ourselves. In the end, it was great that we had negotiated that right because in order to make it work for TV we had to make something that just wasn’t nearly as powerful as our finished feature “Who Took Johnny.” The TV show got pulled when it was supposed to debut because it was scheduled for the Sunday after the Sandy Hook shooting and they ran a special instead. A few weeks later they threw it up on a Thursday night and I don’t think anyone really saw it.

After another year of work on the feature, we premiered it at Slamdance. Unfortunately, we weren’t in competition as that category is only for first- or second-time filmmakers. That made it almost impossible for us to get it attention. That in turn made it difficult for us to get it into other festivals. Still, the audience response was always very powerful, so we knew it would connect if we could get it out, but that took a while. In fact it was well over a year before we could even get a review- which we got from a festival in Greece. Eventually, 6 months later, when the film played at the Sidewalk film fest we got an offer from a sales rep to help sell the film. Actually, that same company had reached out a year earlier but it felt like such a bottom feeder move we blew them off. Once we made a deal, they were able to launch it on Amazon where it immediately shocked everyone by doing 10k in sales in the first few weeks. Unfortunately they also got it on Netflix a month later, where it exploded in popularity. The Netflix sale was not for a lot of money and it cannibalized any revenue we were making from iTunes and Amazon. We just got it back though so hopefully that notoriety will help keep it moving.

“Who Took Johnny” got so much attention because the story is just so hard to believe. As Suki said, she’s never worked on a film where she didn’t have to kind of pump up the drama at some point. In this story the drama amplifies itself. It’s a story that was heavily covered in the press, but almost always in a sensationalistic way. Johnny’s mom was often portrayed as a bit crazy. We decided to tell the story from her point of view and we borrowed a bit from Errol Morris by having her look directly into the camera- because she’s the one telling the story. You can watch it on Amazon or Vimeo.

While working on “Who Took Johnny” we also made a short film called “Under the Bed” which was about our friend Letha, and all of the incredible art that she had stored under her bed. That film only played at one festival the incomparable Big Sky Documentary Film Festival, and when it did I burst into tears during the Q&A. As soon as we made it we put it online and the link to that Video piece is in the post below.

Five years ago we moved back into the house that I grew up in in North Carolina. There were a lot of reasons we decided to try to move from Brooklyn: my mother was moving to a retirement home, our older daughter was going to middle school, there were many films we wanted to finish, and our friend Letha lived in Durham and had stage 4 melanoma cancer. Letha was a good friend to both me and Suki, but she was really Suki’s best friend and we wanted to be close to her. As soon as we got settled in, we went over to Letha’s and hung out quite a bit. She had been working on making collages for years and there were piles and piles of them under the bed. Many of them were simply astounding. She had also taught herself how to paint watercolors and these too were gorgeous. We felt like they had to be seen by others so I started to call around and quickly found a friend with a gallery space where we could set up a show.

I started to write a long thing about our friendship but I remembered that I already had – which is why I am sharing this post rather than just the link to the video. I hope you can take a few minutes to read it and watch the video and spend a little time with one of the greatest artists I ever had the pleasure to call a friend.

“All The Rage” is the most directly personal film that we have made. It didn’t start out that way. Shortly after finishing the final stages of our self-distribution of “Horns and Halos” back in 2003 we embarked on a number of projects including “Code 33” and “Battle for Brooklyn”. While down in Florida for “Code 33” I was playing basketball with our partner David and some friends. At one point I strained my left leg and had to sit out the rest of the game. I was doing a lot of video shooting at the time, jumping in and out of cop cars and walking backwards etc. I was able to do it but my hip and leg got increasingly stiff over time. It was a slightly stressful situation but more than anything I felt like I had to push through it because a lot was riding on the getting the footage we needed.

When the shoot was over the stiffness persisted so I tried to take it easier when I got home, but stretching and resting didn’t seem to help. I remember re-reading Dr Sarno’s book “Healing Back Pain” in order to see if I could get it in check. It got a little bit better, but I was doing a ton of carrying around a small child and that compounded the problem both physically and emotionally. A few months later we stumbled into working on “Battle for Brooklyn” and once again I was working long hours lugging a camera bag and a camera, walking backwards in ice and snow. At the same time we were under a great deal of pressure, especially as young parents, trying to figure out how to make a living making films.

I had spent my 20’s following my passions for music, photography, and film. It was often a struggle financially, but I didn’t need all that much to survive. Shortly before we had a kid we’d bought a house and that was enormously stressful even as it provided some sense of stability. However, stability can also be a weight. Then we had a kid, and that weight got a lot heavier. So did the pain in my hip.

I went to my primary care doctor who dismissed my attempts to discuss Dr Sarno and his mind body perspective on back pain. He also dismissed my concerns about the Atlantic Yards Project because he owned a condo near the project site and he thought it would increase the property value. I should have left in a rage, but instead I took his prescription for physical therapy. Spoiler alert: the physical therapy didn’t help, and neither did the acupuncture I sought on my own. My stress levels continued to increase and my pain got worse. I can recall struggling to walk from the physical therapy appointment on St. Marks place to the subway.

As if trying to take care of a kid, a couple of film projects, and a falling down house wasn’t enough, a month into the “Battle for Brooklyn” shoot we stumbled into an opportunity to buy a foreclosed house upstate for very little. The house had been 80 percent renovated when it was foreclosed upon . It needed a lot of work, but the heavy lifting had been done as it had a new roof, new windows, new boiler and new plumbing. The bank was only asking 50k and someone had clearly recently put about 80k into it. We later found out that the work had been done using a stolen credit card which is why the house had been seized. When things are too good to be true, they probably are. We went ahead and jumped in because it seemed like too good a deal to pass up.

While it was exciting, my stress went through the roof. Soon I could barely walk and I was trying to shoot while using a cane. A couple weeks later after a weekend of trying to get work done on the place upstate in between bouts of trying to un-cramp my calf, I woke up in so much pain I couldn’t move. An emergency call to a doctor got me some Vicodin so that I could be carried to a car and driven home to Brooklyn (by Sander Hicks- the main character in our film Horns and Halos- he was helping me to fix up the house). Over the next several weeks I barely improved as I tried to find a doctor who could help me. It was rough because we had a two year old daughter that I had been doing a lot of the daily care taking for as Suki was editing Code 33.

All the while I knew I should see Dr Sarno but didn’t feel like I could afford it. I think I also felt like I had failed to follow his advice. I believed that he was correct in his assessment that most pain was caused by the repression of one’s emotions, yet I had failed in all of my efforts to make that understanding work for me. Eventually my brother and father insisted that I go to see him. One problem was that I was in such bad shape I could barely get to the car, let alone sit in it and make it into his office. However, by the time the appointment rolled around I was able to muster the strength to go.

It was not a miracle visit, but it was a turning point. His forceful belief that there was nothing physically wrong with me helped me to start believing it myself, and over the next few weeks I improved significantly and became functional. A few weeks later, I asked him if we could make a movie about him and he was happy to participate.

We had made three features films by that point, only one of which was a documentary. We had also shot “Code 33” which was entirely verité- and that’s how we assumed we would make “All The Rage.” We wanted to follow Dr Sarno as he did his work and interacted with colleagues and patients. However, Dr Sarno had no colleagues he interacted with, and his strong ethical position meant that he was not comfortable introducing us to patients. We filmed a couple of research interviews with him. At one point, Suki filmed as we recreated my original appointment so we’d have some footage of him in action. He had a new book coming out, and we hoped to film around its release. When we didn’t hear about it for a while, we asked when it was coming out and were told it was out. He just hadn’t done a single thing to promote it.

We were a bit confounded as to how we might move forward. We knew he had thousands of rabid fans but we weren’t sure how to get a film made. We had applied for a dozen or so grants and got no positive responses. In the meantime, we finished up “Code 33” and continued to shoot “Battle for Brooklyn” and our “Broken Angel” project. Ever so slowly, my pain improved. After a couple of years, I was back to normal for the first time, but felt great disappointment that we hadn’t figured out how to make a film about Dr. Sarno.

When I again found myself on the floor writhing in pain five years later, I knew we had to make the movie and that I had to be a character in it. Before I even began to heal, I was on the phone with Dr Sarno, and furiously taking notes in my journal. I was falling right back in the trap of over doing it, but I was also aware of what was going on. I began to repeatedly listen to a meditation tape of Ashok Gupta’s that my brother had given me. Every time that I did, it would calm me down and lessen my pain. I was stuck on my floor for weeks, but I was determined to make it to Michael Moore’s film festival. I wrote him a personal note urging him not to simply show all the films that had played at the big festivals – and to play ours. He agreed, but I was stuck on the floor. With a a couple of days to go before we were supposed to head out, I was able to crawl up the stairs to my bed. It felt like huge accomplishment and I knew that I could make it.

At 4 AM on the morning of our journey I dragged myself down the stairs. I took a muscle relaxant and a pain killer and it was still torturous. When our car arrived it took me almost a half an hour to get into the car. By the time we got to Newark airport I was a wreck. I couldn’t even sit up in the wheelchair and kept falling out of it in terror inducing pain. When we finally got to the gate, they wouldn’t let me on the plane because I couldn’t sit up. Getting home a few hours later was even worse than the journey to the airport.

Fairly soon after that, I began to improve, and we spent the next several years shooting and trying to figure out how to tell the story. After gathering a lot of interviews and a few important scenes, we started to edit in earnest. We always screen our films many times for small audiences to get a sense of what’s working and what’s not. At first, we got a lot of feedback that people wanted more information that could “prove” Dr Sarno was right. There’s a lot of data that supports his ideas, but it’s not the kind of “data” that in itself creates an “A-Ha” understanding, so people kept asking for even more. Soon, the whole thing was just a boring mess and we realized that data wasn’t helpful, so we stripped it out and began to focus on my personal story. That’s when the film started to work. We did over 50 small group screenings as we struggled to find the right balance of information, Dr Sarno’s story, and my own personal journey. One issue we faced was that Dr Sarno did not want to be a “character” in the film. Fitting into that role either requires playing a part, or being very naked. While he wanted to get the message of his work out into the world, he really didn’t want it to be about him in a substantive way. It took a lot of time but eventually we found a way to balance out his story and my own personal journey.

The film is largely about how our culture shames us for having emotions, so we repress them, which has a negative impact on our health. One of the reasons that I became the character in the film was that I didn’t want to ask anyone else to be as emotionally naked as the part required because it felt somewhat exploitative. In the end, we found that the film had to be personal enough to draw people in, but not so personal that people wouldn’t see themselves in the story. Still, it’s a little bit naked at times. After the first screening, people kept telling me that it was so brave to put myself in it. As it was a very friendly crowd, it didn’t seem all that brave. I felt like Sally Field, “They really liked me”… and Dr. Sarno who got a standing ovation. However, almost all of the reviews of the film personally shamed me for being in the film. Since I was prepared for it, it wasn’t so shocking, but it was a bit disappointing. I knew that the sniping had less to do with me than the fact that the idea that our emotions can cause illness is enraging to a lot of people. While it’s been difficult to get the film written about, we have slowly gotten it to thousands of people and it’s saved hundreds, if not thousands, of people from debilitating pain and illness. I’ll call that a success.

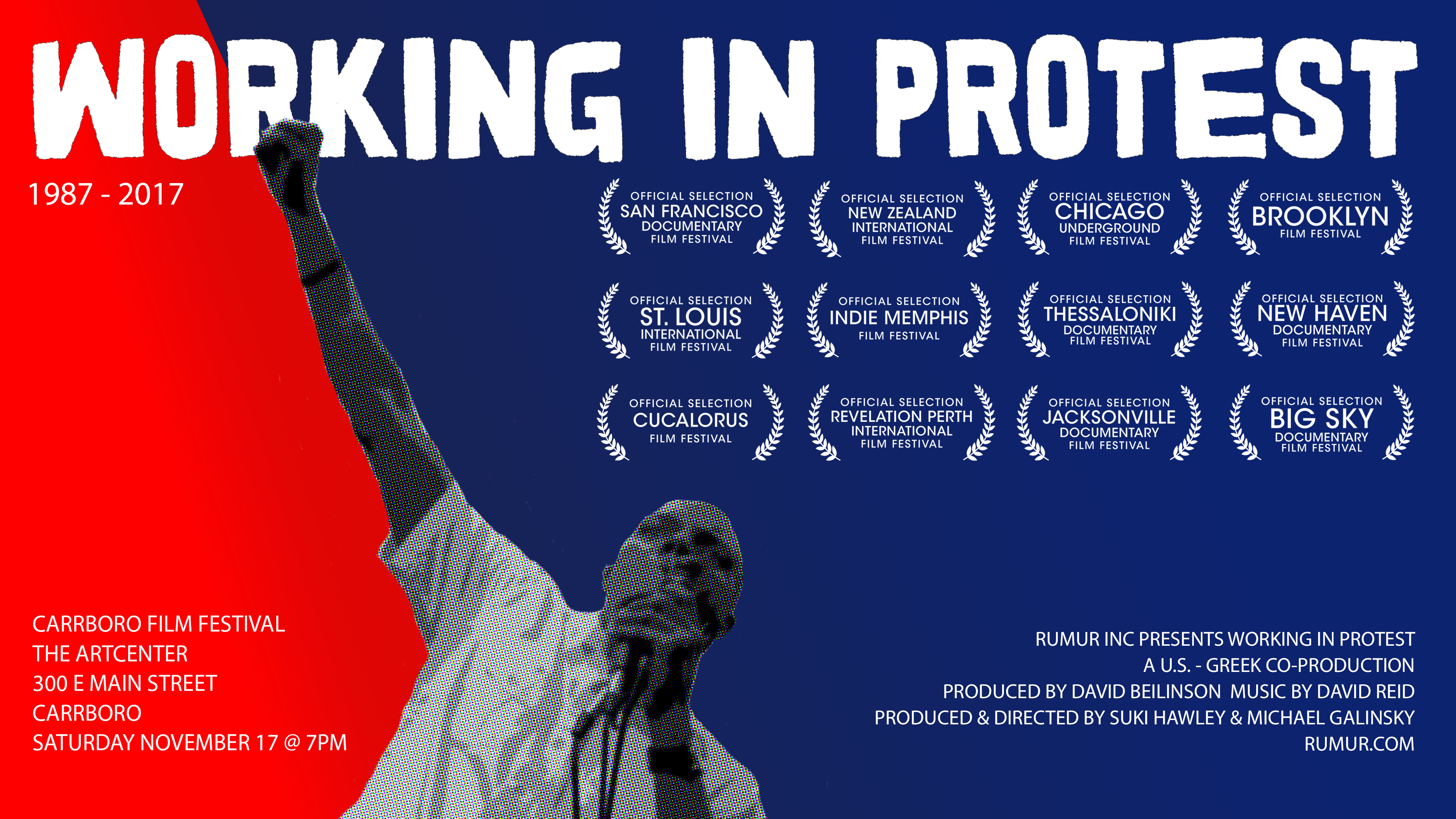

While finishing up All The Rage we made a number of short pieces about protests and political issues. During Occupy we started to document protests with a bit more direction. While we appreciated the advocacy work that was being done around the protests we had the sense that this work was mostly speaking to people who already agreed with the general principles being discussed. We wanted to create work that was a bit more open but also less “journalistic”, as that work tended to over-simplify what was going on. Once we moved to North Carolina we started to shoot more pieces. When I discovered some photos I shot at a Klan rally in 1987 we got connected to sound from that day and made that into a short film. That then sparked an awareness that we had 30 years of work to work with. We wove those pieces into a larger work that raises questions about how to move forward with a culture that is increasingly partisan. It doesn’t provide any answers but it does give us something to think about.

No Comments