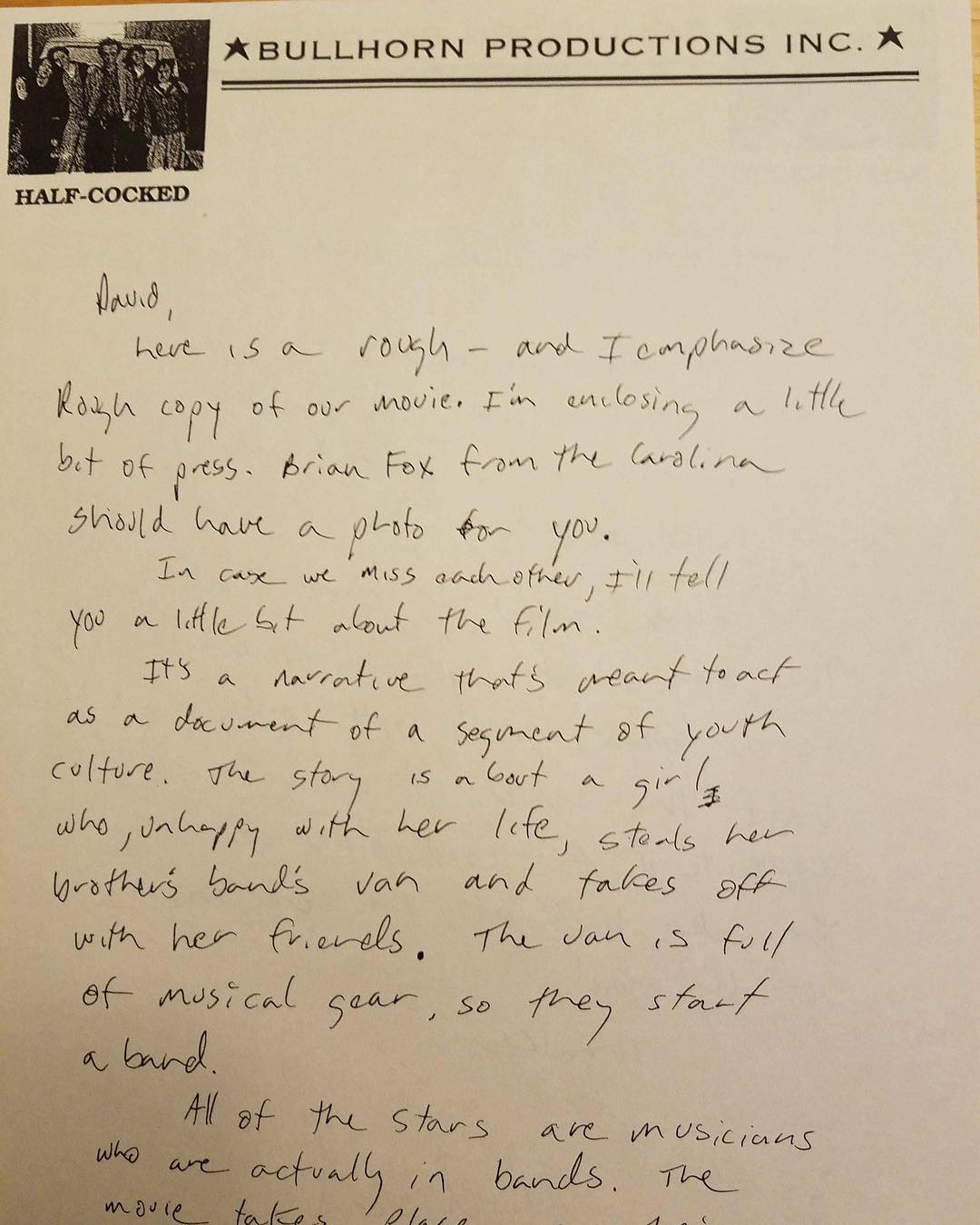

21 Jan Professional Confessional

Last night, just before I shut off my computer, a music writer who I have corresponded with for over 25 years sent me a picture of this press letter I had sent him in 1994. It’s not the most “professional” of letters, and while I’m 25 years older, I’m not sure I’ve become much more professional. During the night, I had a number of stress dreams. They weren’t really nightmares, but my wife tells me that I was tossing, turning, and breathing heavily. I’m pretty sure those dreams weren’t related to this letter, but instead they had a lot to do with having watched “The Darkest Hour” earlier that evening. Something about the pressures that Winston Churchill had to struggle with resonated deeply within me. I don’t think that I am anything remotely like the cunning, curmudgeonly, and brilliant politician. He used his prodigious wit, and wits, to ascend to great heights within the power structure. Yet, at the same time, he resisted intense pressure to conform to accepted ideas. In the film, he is made prime minister in response to Hitler’s blitzkrieg across France, Belgium, and Holland. It’s made clear that he is only in the position because no one else wants it, and he’s the only one who has support from both liberals and conservatives because he’s the only one who has bounced from party to party. In the first war cabinet meeting, he is informed that 300,000 British troops are trapped between the sea at Dunkirk and the Nazi war machine. To a man, every military leader explains that the only way to save their lives is to negotiate a peace: to surrender. Under intense pressure, he struggles with what to do. Ultimately, he resists the temptation to accept defeat. Risking the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of troops, he arranges a civilian battalion of small boats to rescue the trapped soldiers. In the end, his gambit pays off, and the vast majority of troops make it home.

Something about his struggle stuck with me, and though I don’t remember what the dreams were about, I do recall the intense sense of internal conflict that they triggered within me. During our lives, we often feel “stuck”. Perhaps we are stuck in a career path, or a job, or a relationship that isn’t working for us. In these situations, there are things we can control and things we cannot. In our jobs, we have no control over our boss. In our relationships, we have no control over our spouse or significant other. However, we can control how we respond to the pressure we face in these situations, and examining our relationship to our responses can be very instructive. Again, while my life – and my experience – is nothing like that of Winston Churchill, I have often found myself asking questions that people don’t particularly want asked. My mother frequently reminds me that in elementary, jr. high, and high school she often heard from teachers that I challenged them in ways that they did not appreciate. I have no doubt that I asked my questions in ways that made people less inclined to want to answer them. However, their refusal to even entertain these challenges only deepened my sense of cynicism about the structures that define our society.

This morning, as I look back at this sloppy mess of a letter, I find myself thinking a little more deeply about my resistance to “professionalism”. I have never wanted to do things the way they are supposed to be done. This has not made my life easy. Right now, as I wind down from a long year of trying to promote our film “All The Rage”, I’m trying to think about the things that I can control, and how I might have moved forward in a different way. At the same time, there are many things that I cannot control and I’m working on figuring out how to respond to that reality. As we crafted “All the Rage”, we were aware of how people respond to both the information, and the form/style of film. While we certainly wanted the gatekeepers at festivals, press outlets, and distributors to appreciate the work, we labored to make something that would help people to expand their consciousness rather than affirm it. Unfortunately, this means that it is just challenging enough for many people, that they reject it. Even knowing what we know now, I’m not sure we could have made it much differently. In “The Darkest Hour”, when Churchill is under his most intense pressure from others in the government he jumps from his chauffeured vehicle and disappears into the underground subway system. There he queries “average people” about whether to surrender to the Germans or fight back despite the costs. The response is unwavering support for resistance. Sometimes those in power lose touch with the people.

Art has a funny way of becoming what it needs to become. While the challenges we have faced in our “career” (i.e. we can’t seem to get our films past these gatekeepers) indicate that we should be doing something differently, the films clearly resonate with audiences. While we have faced both resistance and indifference to the mind-body message of “All The Rage”, we have also found passionate support among audiences. I think that this is the frustration that I was struggling with as I slept last night. I can’t control the gatekeepers. While I can control my response to the reality of them, it is an internal struggle that I will continue to deal with. In the meantime, I will also continue to connect with the emotions that drive the whole process in order to become unstuck.

No Comments