23 Apr Rage and Fear

Rage and fear are intimately connected – which can be see in the way we often respond with rage when we feel threatened and feel fear when we are confronted with rage. Sometimes these perceived threats are physical and sometimes they are emotional. When rage is directed at us, we often default to an automatic response of fight of flight- or even both at the same time.

Rage and fear are blinding to some degree because all of our attention is focused on escaping the threat. In this state of hyper focus, we lose a lot of our perspective. When we feel like we cannot escape the threats we face, we develop coping mechanisms because our bodies and our minds simply can’t function if we are consciously in a state of fight of flight. We do this by repressing the fear and rage, and we distract and numb ourselves from the overwhelming feelings. However, when we repress our rage and fear, it doesn’t mean that we no longer react to threats, but instead that these reactions become both habitual and repressed. The state of high anxiety comes to feel normal. When this stress energy is created – and we don’t process or release it – it builds up in our bodies. By repressing our emotions, we become both less aware of the world around us and more profoundly reactive to perceived threats or insults.

The good news is that when we become more aware of how both fear and rage drive our responses in the world, we have the ability to respond more thoughtfully. Rather than react without thinking, we can be thoughtful about how our response will play out. When we take on a more “accepting mindset,” we can rapidly decrease the amount of stress we build up in our bodies.

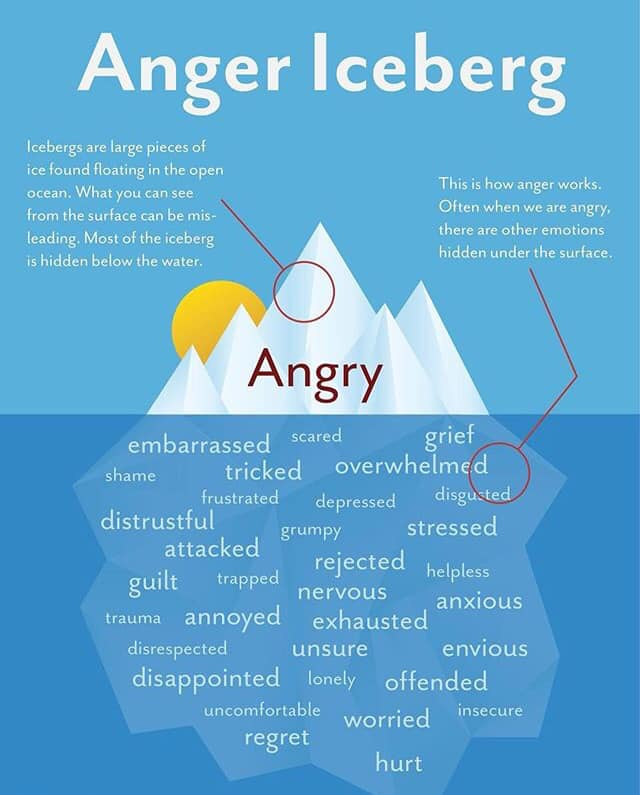

In order to function in society, we can’t walk around reacting as if we are in a state of fight of flight because this is socially unacceptable behavior. Again, this leads to the repression of these thoughts and feelings and they often manifest in ways that don’t immediately resonate as “rage” or “fear.” Sadness, anxiety, shame, guilt, and depression can often be a disguise for our anger.

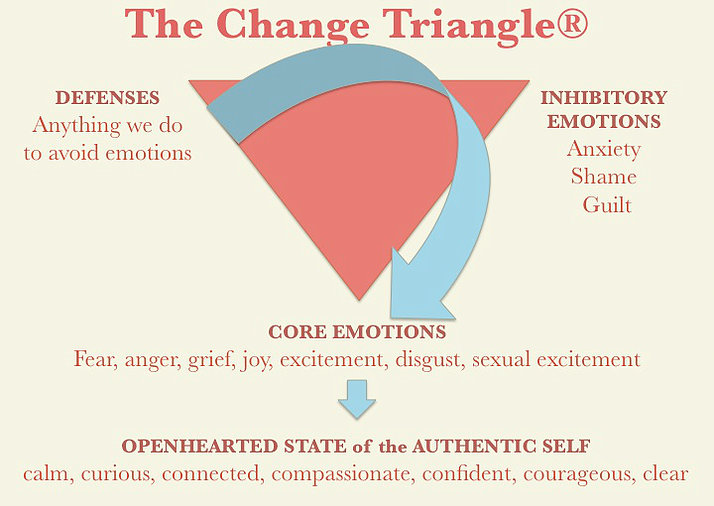

In her book “It’s Not Always Depression,” Hilary Jacobs Hendel does a great job of zeroing in on the idea that we have core emotions, inhibiting emotions, and defenses. Using a diagram called the Change Triangle, she explains how we are often taught to resist our our main physical reactions to the stimulus in the world around us. These “core emotions”- fear, anger, grief, joy, excitement, disgust, and sexual excitement – tend to give us vital information. They help us understand when we are we in danger, or when we are safe and comfortable. Hendel notes, “Core emotions are hard-wired in the middle part of our brains, meaning they are NOT subject to conscious control. Triggered by the environment, each core emotion is pre-wired to set off a host of physiological reactions that prime us for action.” However, we are often taught that our reactions to these emotions are socially unacceptable and we learn to repress them. When that happens, we develop inhibitory emotions to protect us from these “unacceptable” reactions to the world.

Hendel goes on to explain, “Shame, anxiety and guilt, the inhibitory emotions, block core emotions: 1) when they are in conflict with what pleases others whom we need like parents, peers, and partners; 2) when core emotions become too intense and our brain wants to shut them down to protect us from the emotional overwhelm.” She further explains that in addition to inhibitory emotions, we use defenses like sarcasm, distraction, and negative patterns of thinking to distract ourselves from the inhibitory emotions which are covering up our discomfort with our core emotions. These patterns of thinking, reaction and behavior become central to all of our relationships, yet for the most part we have very little awareness of how these patterns play out. When we are able to illuminate these patterns for ourselves, we can learn to respond differently.

Imagine for a moment a father whose child is having a tantrum in a public place. The father might not want to be judged for yelling at his child (shame), so he holds in the anger and tries to calm his kid, but the energy withheld is still felt by the child and the tantrum does not abate. The father might not even notice that he’s holding his breath and not being present with his child because he’s preoccupied with a fear of being judged by others. His failure to calm the child might lead to a complex stew of reactions, including shame which might lead to anxiety as a distraction from that shame. When he can’t regain control over the situation, the internal pressure might grow, and the energy expended trying to hold it in grows as well. The tension can become so high that the parent can’t see a way out of the situation. Quietly, or loudly panicking, their blindness to the situation only causes the fire to burn brighter.

An outside observer might immediately see what’s going on while the parent stumbles forward helplessly. After a while, the tantrum, like any storm, might blow past, and the father is likely left feeling confused, depleted, and sad. This sadness is perhaps a distraction from the core reaction of rage. Perhaps the father doesn’t repress that rage and reacts to the child’s tantrum with anger. This too is blinding. If the parent’s desire is to support the child, anger is not a useful solution. However, when we are in a rage – or overcome with sadness, depression, or anxiety – we have less capacity for empathy. Empathy can be confusing when we are caught up in our own dramas because empathy often is in conflict with our ego’s desire to be in control.

The simple idea that what we feel is often just the tip of the iceberg is central to all mind body interventions. I’ve spent the past decade focused on getting a deeper understanding of how this plays out in my own life as a child, a partner, and a parent. Hard won insights have led to both healthier relationships and a healthier body. Even with all of the work that I have done, I still fall into these deeply-rooted patterns regularly. However, I rarely get overcome with rage anymore. When I find myself feeling angry or hurt, I take a moment to reflect on the framing that caused that reaction. For example, my mother will often dismiss my concerns by pointing out that I “think I know everything”. For as long as I can remember, when she feels challenged, she responds by dismissing and diminishing me. This often enrages me, and frankly it got to me this week. Understanding this helps me to step back and recognize that my anger has much more to do with me than it does with her. When I can accept that her defensiveness runs deep, I can find empathy for her and let my anger go.

These issues don’t affect us only on the interpersonal level. So much of our culture is now subsumed with rage-driven responses to the world. Liberals attack Conservatives, and racists fight with anti-racists, and all of them de-humanize the other. Things can feel a bit hopeless. Over the past couple weeks, I’ve started to counteract this energy by reaching out to people with positive affirmations and gratitude. Shifting my awareness away from the negative doesn’t necessarily mean repressing those emotions but instead re-training my brain to also see the complexity which includes many positives. The truth is, when we give people positive feedback they feel better, and the respond in kind. We create our environments through our energy and our actions. When we live in fear, we manifest fear. When we live with a sense of infinite possibility …. infinite possibility becomes a reality.

No Comments