31 Dec Sarno will not Save you

Sarno can’t save you. His ideas and his work can point you in the right direction, but in the end, no doctor can heal us; they can only help us heal ourselves. The truth is, you can save yourself by shifting your perspective to focus a little more on your emotional health rather than just your physical health. When we repress our emotions, we create dissonance within our bodies that manifests itself in a physical way. If we pay attention to what our physical symptoms reveal about our emotional health, we can find a path towards healing. If we ignore those messages from our body, we can expect those symptoms to get louder. For what it’s worth, the title of this post is kind of a joke because the subtitle of our film “All The Rage” is (Saved by Sarno).

In the late ’60’s, Dr. Sarno came to understand how this simple truth could create back pain and, after discovering the profound connection between emotions and pain, he spent years developing a deeper understanding of the ways in which the repression of emotions cause such great discomfort. Over time, he realized that fully understanding and embracing the power of this connection was an essential part of healing. For many years, he was alone in the wildness as his colleagues ignored him. However, increasingly, other doctors have come to the same conclusion, not just in regards to pain but in relation to all illness. Dr. Gabor Mate writes about this connection in relation to auto immune issues in “When the Body Says No“, Dr. Dave Clarke writes in relation to gut issues in “They Can’t Find Anything Wrong“, and Dr. Wayne Jonas covers this in “How Healing Works“. Jonas, a respected scientist who has spent years looking at studies of studies, came to the conclusion that overall, fully 80% of healing comes from within, and only 20% comes from “a healing agent” provided by a doctor. Dr. Clarke adds, “I worked with many patients who presented a range of skepticism about mind-body treatment by assuring them I would simultaneously continue to use evaluation and treatment based on an organ disease approach. As they saw results from mind-body, their skepticism would fade.” While the power of the mind body connection is profound, most people are wildly resistant to it. Unfortunately, belief plays a major role in healing and Dr. Sarno found that if people could not believe that their emotions might be a causative factor of their pain, then they wouldn’t get better with his counsel. Belief, and awareness of what was going on, was central to his process. As he stated, his prescription was knowledge. It became very clear to him that people’s deep-set resistance to acknowledging their own emotions often kept them from healing.

This is a real Catch-22: in order to heal, one has to acknowledge these emotions, but the reason they are in pain in the first place is because they have such a powerful resistance to acknowledging them. Sarno found that those with the greatest resistance to feeling and acknowledging their emotions had the most difficult pathway towards healing. In fact, this resistance, which they were often not fully conscious of, made it almost impossible for them to get better. Conversely, he found that for people who made the connection right away, healing often came with surprising speed. Still, there were others who understood his concepts, and did the work to connect to their emotions (journaling, therapy, thinking emotionally rather than physically) who struggled to get better.

As he honed his understanding of treating this mind body disorder, Dr. Sarno found that some people needed scientific evidence in order to move past their fears, while others connected more through stories. Over time, he developed a program in which he first thoroughly examined a patient in his office to rule out a structural problem like a broken bone or a tumor. He then had the patient come to one of his lectures where he laid out all of the evidence that supported his understanding of the syndrome. After this, he invited them to attend small group meetings with other patients in order to have a supportive space to discuss the difficulties they struggled with. Not everyone healed, but he found vastly more success in treating patients with this method than with the “standard care” he had been taught to practice. While some people complained that his methods weren’t based on “science,” he countered with the fact that there was no science to back up the standard care he had been taught either.

After years of doing this work he eventually decided to pre-screen patients by asking them over the phone if they thought that they could accept the idea that their pain might have an emotional basis. If they insisted that they could not, he suggested that they see someone else. He knew that he could not help these people. He could only point them in the right direction, and if they were unwilling to look in that direction, there wasn’t much he could do. Many skeptics say that his self-reported data on patients who healed is meaningless because he turned away patients who wouldn’t “buy-in” to his concepts. However, if a patient told a physical therapist that they wouldn’t do the exercises they were prescribed, it would make no sense to go to that therapist. If one goes to a therapist and refuses to believe it will help, it’s not likely it will help. In fact, my brother often cites a study on the efficacy of psychotherapy. In this study, people were asked about the type of therapy they thought worked the best. They were then randomly assigned to different types of therapy. It’s not so surprising that those who went to the type of therapy that they though would work tended to work for them.

I’ve been thinking about this idea of the import of shifting our perspective because the issue keeps cropping up in conversation. A few days ago, I saw a friend of mine who has become a very serious runner. Last year around this time, I saw him a few months after he ran a marathon and found out that he hadn’t run since because of a leg pain. As it had been several months and the pain hadn’t “healed,” I figured it might be a mind body issue. Sometimes, we have a fear response to pain that signals to the brain that there is danger. The brain then sparks more pain in order to protect us from the perceived danger, and the only way to deal with it is to retrain the brain to stop creating the danger signal. I learned this first-hand when my knees started hurting while going up stairs. I noticed that it didn’t hurt as bad when I ran, so I decided to run up a hill fiercely while telling my brain that my knees were fine. A few hours later, we went to a friend’s house where I had been having trouble with the front steps. This time, I bounded up them with no problem. It was a powerful lesson to me. I told my runner friend that story and made him come outside to run a half mile with me. Neither of us had on running shoes, but we jogged for a while. His leg was very tight but we talked through it, and I instructed him to talk to his leg and to consciously let go of the fear that he was injuring himself. Within a week, he was back to running and soon he was running almost as much as he had before.

Earlier this week, another friend was in town and told me that they had gone for a five mile run together after the friend with the previously hurt leg had run thirteen miles that same morning. He came to the party we were at a few minutes after I heard this and his wife said that his legs are almost always in pain, but he runs through it. He kind of played down how much pain he’s in, and he knows that he’s not doing damage, but my guess is that he’s not doing the other part of the Sarno work, and focusing on his emotions. Frankly, I think it’s clear that there is still some emotional work to do (and I’m going to encourage him to do that by sending him this post;)

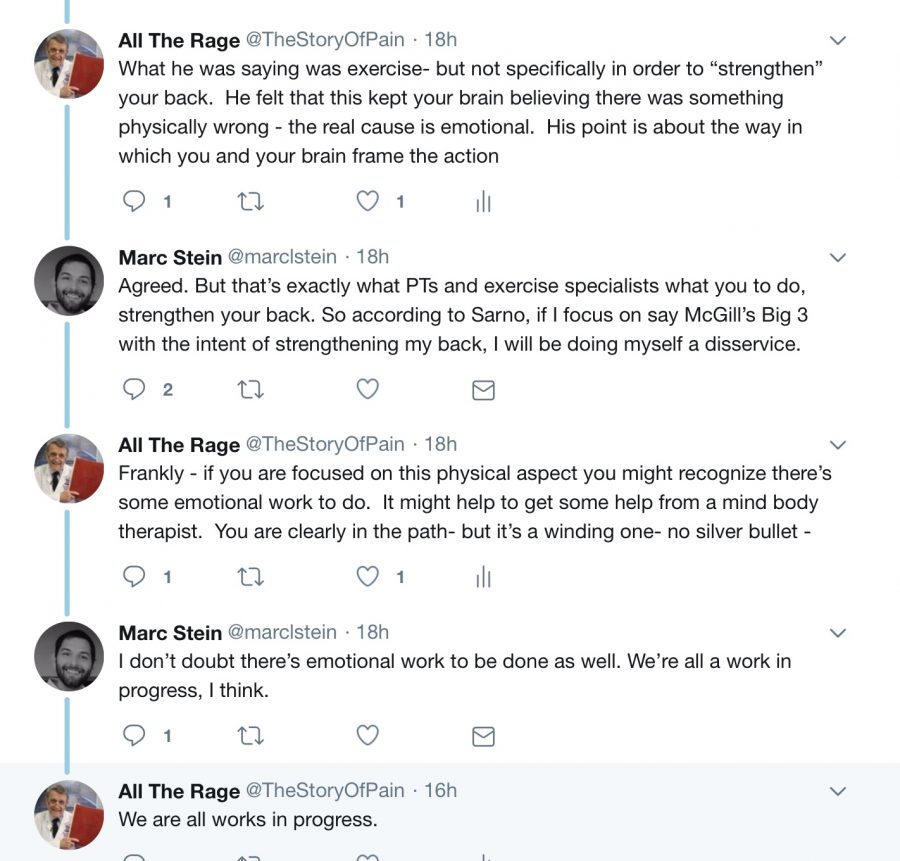

@cjramin I love your book! Question for you. You put great importance on exercise but also seem to greatly admire the work of Sarno. Are the two not contradictory? I ask this as someone who finds Sarno extremely compelling, yet I’m still searching for relief.

— Marc Stein (@marclstein) December 30, 2018

I was also thinking about this idea yesterday, about having emotional work to do, because someone on twitter tweeted the message above to Cathryn J Ramin, author of “Crooked: Outwitting the Back Pain Industry and Getting On the Road to Recovery” about the dissonance between her chapter on Dr Sarno and her chapter on Dr. Stuart McGill and his “big 3 back exercises”. He continued, “I’m just struggling with the contradiction between a Sarno approach and (back specific) exercise approach I want to work on both but feel it’s contradictory, at least according to Sarno. McGill might say I need to strengthen my back, Sarno would say I’m fine.”

I responded with the following note,

Dr. Sarno says get back to movement and exercise as soon as possible -what might be confusing you is his admonition to not become obsessed with exercise or PT or they will simply become a replace the distraction and obsession- instead exercise AND be aware of the emotions

— All The Rage (@TheStoryOfPain) December 30, 2018

he replied

I enjoyed your film! He doesnt just say not to obsess with PT/exercise, he says to discontinue any treatment that presupposes a physical disorder. Resuming normal physical activity is not the same as back specific exercises “Exercise for the sake of good health is something else” pic.twitter.com/zCULih1Voj

— Marc Stein (@marclstein) December 30, 2018

I understand all of this pretty well because I spent years struggling to change my perspective with little success. It took being slammed to floor with the force of a dozen elephants, and being stuck there for weeks, to begin to turn my ship around. In those first crazy days of wildly intense pain and anxiety, I had profound and striking revelations that involved wild physical reactions. By paying attention to what was going on from an emotional perspective, I was able to see just how powerfully my unconscious thought patterns kept me locked into a seemingly invisible prison of my own creation. Once I saw the bars though, they ceased to be solid, and I began the long, slow process of unwinding some of those patterns. I too had struggled to see the difference between doing back exercises in order to strengthen myself in general versus doing them because it meant focusing on a physical cause of my pain (rather than a truly emotional cause). I have not dug down to the roots of all my problems, and don’t believe I need to. Instead, I have developed my capacity for seeing how emotions shape my reactions and I’ve learned to respond with more awareness rather than react with unconscious emotion. As the tweet above says, I am a work in progress – but I can say with confidence that I am making progress. Still, as I write this, I continue to acknowledge to myself just how much work I have left to do. I’m not talking about becoming perfect. Instead, I understand that I have a lot more work to do on letting go of those frames that keep me trapped.

No Comments